Americans are fat and getting fatter. But now pharmaceutical companies are rolling out new prescription drugs that really do help people lose and keep off significant amounts of body fat. Celebrities like Elon Musk have touted their benefits. The side effects appear minimal, but the weight stays off only as long as users keep injecting the drugs weekly.

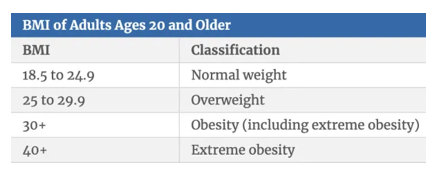

The share of overweight Americans has been ticking relentlessly upward. In 1960, 31.5 percent of adults in the U.S. were overweight (13.4 percent of whom were obese); today, 73 percent are overweight (42.4 percent of whom are obese.). Overweight and obese are defined as having a body mass index over 25 and 30, respectively. A body mass index measures the ratio of a person's height to his weight to roughly estimate his amount of body fat.

The increase in weight has been accompanied by a rise in the number of Americans diagnosed with diabetes, which rose from 5.5 million in 1980 to 28.7 million in 2020. Around 96 million Americans have prediabetes, a condition characterized by slightly elevated blood glucose levels, regarded as indicative that a person is at risk of progressing to Type 2 diabetes.

A 2017 study estimated that "care for people with diagnosed diabetes accounts for 1 in 4 health care dollars in the U.S." That amounted to $327 billion, including $237 billion in direct medical costs and $90 billion in reduced productivity.

And not just Americans are getting fatter. Worldwide, 39 percent of adults are overweight (of whom 13 percent are obese). Earlier this month, the World Obesity Federation (WOF) projected that if current trends continue, more than half world's population, around 4 billion people, will be overweight by 2035. Two billion of them will be obese.

Various epidemiological studies find that obesity correlates with shorter life expectancy and worse overall health. The WOF study estimates that the economic impact of overweight and obesity will reach $4.32 trillion annually by 2035, about 3 percent of global GDP.

Now, several new drugs initially developed to treat diabetes also help users lose body fat. The New York Times called them "a game changer." The Washington Post hailed the new weight loss drugs as "a milestone for the obese," while worrying that the poor will not have access to them. "Weight-loss drugs will be tech breakthrough with most direct effect on people," asserted an op-ed in The San Diego Union-Tribune. The Economist declared, "New drugs could spell an end to the world's obesity epidemic."

The drugs, semaglutide and tirzepatide, are better known by the brand names they're marketed under: Ozempic, Wegovy, and Mounjaro. Both drugs work by targeting specific hormones to suppress appetite, reduce food cravings, and improve control over eating with the result that users lose body fat. (Basically, the antithesis of the black market "fatkins" treatments that supercharged metabolism to burn off fat in Cory Doctorow's 2009 novel Makers.)

So how much body fat do users tend to lose? One study reported that users of the Wegovy semaglutide and the Mounjaro tirzepatide lost, on average, about 12.4 and 17.8 percent of their starting weights, respectively. Depending on which drug he takes, a male standing five feet 10 inches and weighing 240 pounds would likely lose about 30 or 45 pounds. This would lower his BMI from obese to overweight and lower his average blood sugar levels (A1C) while improving various measures of cardiovascular health.

Chronic illnesses are generally thought of as long-lasting conditions that frequently can be controlled but not cured. Many medical practitioners and researchers regard obesity as just such a chronic illness. Consequently, as a chronic condition, obesity needs chronic treatment. When users stop taking the new weight loss drugs, their feelings of hunger return and they rebound, regaining about two-thirds of the weight that they had lost, according to a 2022 study.

The current average price for the new weight loss injections is around $13,000 per year. Making the absurdly heroic assumption that all 88 million obese American adults were to take them, it would total around $1.1 trillion annually. For comparison, a 2018 Milken Institute report estimated the impact of excess weight on the U.S. economy at $1.7 trillion, including $481 billion in direct health care costs and $1.24 trillion in lost productivity. Already spending a fiscally unsustainable $1.7 trillion annually on health care, the federal government should not and will not be funding these weight loss treatments. The best way to make these medications more widely available is through drug company competition.

The cost of Ozempic when prescribed to treat Type 2 diabetes is covered by most private medical insurance plans and Medicare. However, people seeking to use the medicines for weight loss generally have to pay out of pocket. The good news is that other pharmaceutical manufacturers are already working on rival products, including Amgen, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca.

The post The End of Obesity? appeared first on Reason.com.

.jpg?w=600)