When overwhelming favourites lose to rank underdogs, it’s often the case of the mighty underestimating the hungry. Overconfidence is a flaw that comes into sharp focus in the ring, where Muhammad Ali, Mike Tyson and Lennox Lewis all invited shocking defeats against the unheralded Leon Spinks, Buster Douglas and Hasim Rahman, respectively. In boxing, complacency is more dangerous than an uppercut.

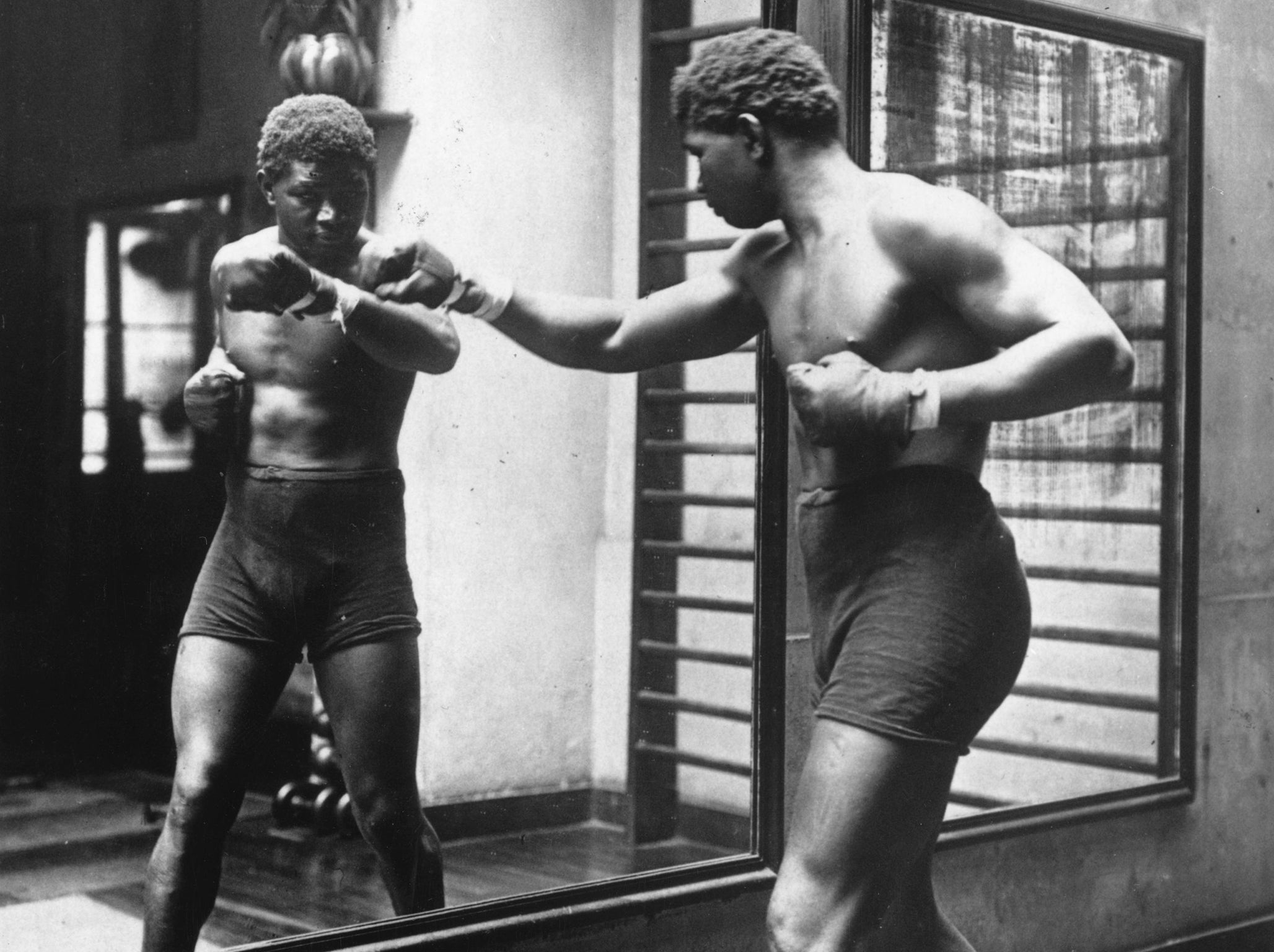

Ring legend, Georges Carpentier, was the nation’s darling in post-World War I France. All of Paris expected their decorated war hero and handsome film star to deliver an easy defence of his Light-Heavyweight world title against a huge underdog from Senegal, called Battling Siki. But September 1922 saw one of the biggest ring upsets of the 20th century, as Siki knocked out Carpentier to become Africa’s first World Champion. And yet it was a mere chapter in the extraordinary but largely forgotten life story of Siki; a story punctuated by corruption, racism, heroism and murder.

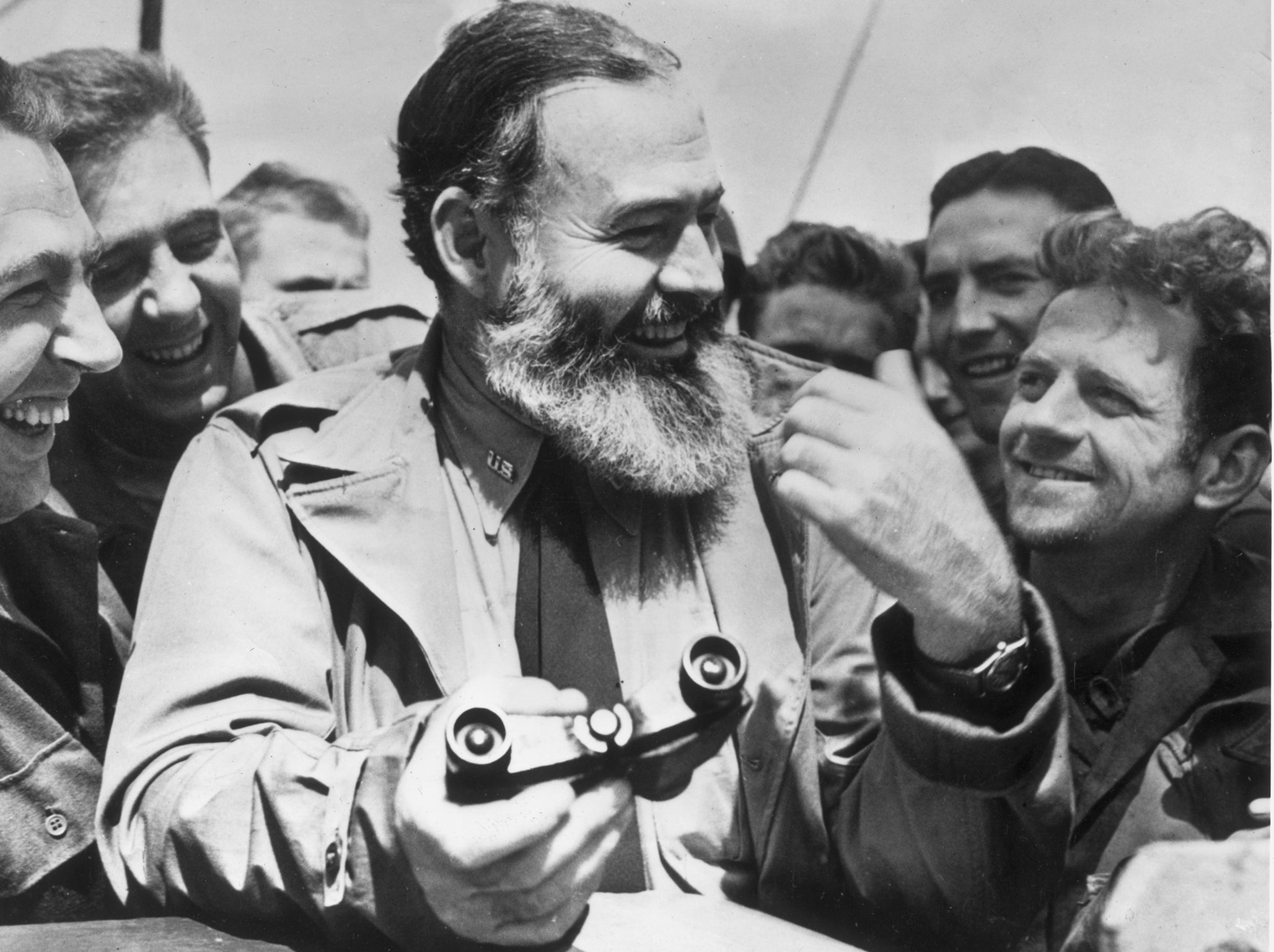

Ernest Hemingway was among the 55,000 people at the Buffalo Veledrome that night as Carpentier put Siki down twice early in the fight. However, when Siki rose from the canvas a second time he did so with renewed determination. Frustrated, Carpentier resorted to foul play to try and bring about the desired result. His headbutts only served to enrage Siki who subjected the champ to a barrage of unanswered punches before he was counted out in round six.

To everyone’s surprise the referee then awarded the bout to the prone Carpentier, claiming that Siki had tripped him and was therefore disqualified. The crowd was incensed and protested forcefully. The judges then overruled the referee and declared Siki the new world champion. That moment of glory, a moment that should have been the dawn of great fortune, was merely the beginning of his troubles.

Siki was born Louis M’Barick Phal in Saint-Louis, then the capital of the French colony of Senegal, in 1897. At the age of 8 he came to France and at 15 began boxing professionally before his career was interrupted by the outbreak of war.

He joined the Eighth Colonials, fought at Gallipoli and was injured at the Somme, earning the same medals as Carpentier, the Croix de Guerre and Médaille Militaire, after displaying incredible bravery in battle.

After his honourable discharge, Siki resumed his boxing career, fighting in France and in Holland where he met his first wife, Lyntje, with whom he had a son, Louis. An impressive run of victories led to his tilt at the world title.

Siki was the toast of Paris after his momentous victory. He hosted a champagne banquet to celebrate and bought two lion cubs that he would parade down the Champs-Elysees, throwing money to strangers.

But while Siki celebrated, Carpentier’s manager and trainer, François Deschamps, tried every machination to get their fight annulled. When Siki was censured for shoving another boxer’s manager, the Fédération Française de la Boxe, on whose board Deschamps sat, suspended Siki and stripped him of his French and European titles.

Siki then challenged the very integrity of French professional sport. He reported he had agreed to throw the fight, but had reneged when he felt the terms changed mid-bout. He was to go down in the first round to indicate the fix was in, and then again in the third, which indeed he did. He agreed, he said, on the understanding that he would not be unduly hurt. Carpentier hit him hard in that second knockdown and when Siki helped his opponent off the canvas after a misjudged headbutt saw him fall, he was hit with a sucker punch. The fix was out.

The FFB had barred Siki from boxing in France but did not have the authority to take away his world title. So he arranged to defend it in London against Joe Beckett, a British heavyweight. Olympia was booked for December 7th, 1922, however the Home Secretary, W.C. Bridgeman, ruled that the bout must not take place for fear of how it might be perceived throughout an Empire fundamentally based on the fallacy of racial superiority.

Siki finally found a venue in perhaps the only place a black champion could defend his title; a place already in the midst of a civil war - Ireland. If the Irish government could put on a major sporting event it would show the world it really was in charge of a functioning state, not a country at war. Amid high tension, with death threats, gunfire and attempts to bomb the venue, the Scala Theatre, Siki fought an Irish journeyman, Mike McTigue. He lost a close decision to the home fighter, in Dublin, on St Patrick’s Day, perhaps predictably.

With his options narrowing, Siki set sail for America. There, he struggled to gain a license but was able to earn money fighting exhibitions in Canada with retired heavyweight champ Jack Johnson. When the Boxing Commission finally relented they insisted he meet the feared Kid Norfolk, despite Siki being nowhere near the level of fitness required for a test that stern. Siki put in a great, brave performance at Madison Square Garden in a fight of the year contender. Norfolk took the decision, but Siki’s reputation had only been enhanced.

Siki remained a source of fascination to the press, whose coverage was so steeped in prejudice it would have been comical, if it hadn’t been so offensive. He spoke five languages with a ready wit and warmth, but was frequently depicted as some kind of savage.

“A lot of newspaper fellows have written that I have a jungle style of fighting, and that I am a sort of chimpanzee who has been taught to wear gloves. I was never in the jungle in my life,” he said. “I am Senegalese and I am proud of it. I am black and where I am from it was very fashionable,” he told L’Auto.

Siki married a second wife, Lillian, and settled in New York. When fighting in the south, he, a former world champion, was not permitted to stay in the same hotel as his white manager, Robert Levy, who was doing a quite terrible job of guiding his career. Fights became harder to come by, along with fair decisions, and big paydays disappeared from the horizon. Whether through disappointment, or inclination, Siki neglected his training, but not his drinking, even in Prohibition America. It was said that his idea of preparing for a fight was to go to a bar, get drunk and then refuse to pay. He would then fight his way out and into ring readiness.

In Hell’s Kitchen he was well known to the police, who liked him, even though he was a frequent ‘guest’. When he had money - just after a fight - he was generous with it, buying drinks for all and sundry.

He was in a familiar state of disrepair when he ran into a cop late one night in December, 1925. Patrolman Sheehan advised him to go home. A block from his apartment, a gangster put a bullet in the back of his head. He crawled towards home before another bullet in the back finished him off. He was 28.

Siki was buried in Flushing Cemetery but, after a lengthy campaign, his remains were moved from Queens to Saint-Louis, Senegal, the city of his birth, in 1993, where it is hoped they will inspire future African champions.

Georges Carpentier died in Paris, aged 81. In 1991 he was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame (IBHoF). This year, the IBHoF will consider Battling Siki’s nomination for induction for the first time. Maybe the tale of this irrepressible and historic fighter will finally be preserved for posterity after all.