Many years before I encountered Hugh Brody’s writing, I read Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book (1894). This was the first book I remember that significantly influenced my life. I read it many times, and still regularly re-read Kipling. The Jungle Book is a colonial version of the “wild child” story: it explores the withdrawal of human care, and acceptance into a different world of nurture and home set amongst danger, enmity and death.

The child raised by wolves finds himself appalled and confused by the insistent hierarchies of colonial Indian human society, instead negotiating his unique place with the non-human inhabitants of the jungle.

I was born in India, and the Jungle Book rubbed shoulders on the bookshelf with worn copies of Salim Ali’s The Book of Indian Birds (1941), E.P. Gee’s Wildlife of India (1964), and Jim Corbett’s Man-Eaters of Kumaon (1944) and the poetically beautiful My India (1952).

The wildlife guides were the factual complements to the poetry and drama of Kipling’s and Corbett’s stories. Wild societies where humans and animals share space. Journeys in the remote landscapes of colonial India. The deep knowledge and wisdom of local hunters.

These stories were signposts on a circuitous pathway eventually leading to a PhD in geography, investigating the relationships between Aboriginal people and conservation agencies in Australia.

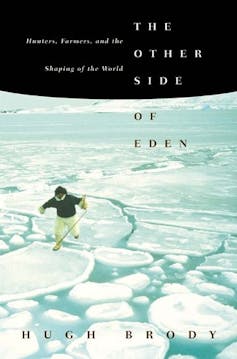

The year I submitted that thesis, anthropologist and documentary filmmaker Hugh Brody published The Other Side of Eden, subtitled Hunters, farmers and the shaping of the world (2001).

I was back from months of fieldwork in Cape York, living with people who, when they could, lived from the land. Brody worked for decades in Canada’s far north, documenting Inuit and Indian perceptions of their lands and the impacts of colonial relations.

Reading The Other Side of Eden did three things – it gave me a radical new way to understand the position and history of Indigenous peoples, and specifically hunter-gatherers, in the world today. It reminded me of the debt I have for the generosity, friendship and gifts of wisdom from my Aboriginal co-workers. And it reinforced the power of story.

The Other Side of Eden takes readers deep into the world of Arctic peoples. Brody uses immensely detailed ethnographic observation of hunting practice, arctic travel, language, child-rearing and many other elements of culture to demonstrate the wrongness of conventional views about such peoples.

Despite the massive expansion of agricultural peoples all over the world, hunter-gatherer societies have persisted, in areas considered marginal to the dominant societies. It is these hunters who are intimately tied to place, unlike the restless farmers always seeking growth as their populations increase.

Care and respect

“All humans have been evolving for the same length of time”, writes Brody, so it is not a question of hunters being further back on some linear trajectory of development: it is a choice. Brody writes,

the hunter-gatherer mind is humanity’s most sophisticated combination of detailed knowledge and intuition.

Hunter-gatherers “oppose hierarchy and challenge the need to control both other people and the land itself”. He continues,

the egalitarian individualism of hunter-gatherer societies, arguably their greatest achievement and their most compelling lesson for other peoples, relies on many kinds of respect.

Brody makes a strong case for the difference between respect and control:

Rather than seeking to change the world, hunter-gatherers know it. They also care for it, showing respect and caring for its wellbeing.

All these communities have rules about the treatment of animals, plants and the land itself – specific, overt rules about which animals or plants can be taken at which time and in which place and in which way.

These processes of respect can be interpreted functionally (for example by not disturbing an animal during the breeding period), but Brody emphasises that they are also about relationships: if people do the right things “the creatures and plants they eat will feel welcome and know they are respected”.

Describing a hunting companion, Brody says:

He often travelled alone, over great distances, hunting day after day. Everything he killed he treated with care and respect. No kill was careless, nothing was wasted; everything was known, understood.

Like Brody, I was a white man from the south (qallunaat in his case, migaloo in mine), and also like Brody, I worked on land claims. While Aboriginal people shared much specific knowledge about their Country necessary for that work, they also, through metaphor, emotion and example, worked to help me understand the limitations of my worldview and the beauty and intricacy of theirs.

‘Heart teachings’

In my writing I did not engage with this – what I think of as “heart teachings” – for many years, instead dutifully conforming to the “objectivity” and “evidence” demanded of academics.

But I did engage with it in my teaching. I combined Brody’s title with the title of my thesis, and wrote a subject called Redefining Eden: Indigenous Peoples and the Environment.

In this subject, Aboriginal guest lecturers described continuities of customary harvest practice and caring for Country from the deep past, as well as their experience of contemporary conservation and environmental management. More than 1,000 undergraduates completed that subject, I received numerous comments about how the subject influenced them, and my Indigenous teaching partners and I received several teaching awards.

Brody is a wonderful writer, and one of the great strengths of The Other Side of Eden is the skilled and poetic weaving together of field notes and personal anecdotes – lived ethnographic experience – with scholarship, and that’s what we did in our teaching.

Many Aboriginal co-teachers shared stories of their lives, giving a window into a world few are privileged enough to experience. Those stories grounded and made real the theoretical material we investigated.

Read more: Friday essay: this grandmother tree connects me to Country. I cried when I saw her burned

Most hunter-gatherer societies have experienced catastrophic, world-ending impacts from colonial oppressors, and have persisted through those changes. As broader society recognises and begins to face new forms of world-ending, what are the lessons from Indigenous and hunting societies?

There are clues in Brody’s work: “The hunter-gatherer seeks a relationship with all parts of the world that will be in both personal and material balance”, and

the balance of need with resources; the reliance on a blend of the dreamer’s intuition with the naturalist’s love of detailed knowledge; and the commitment to respectful relationships between people [and others].

Brody also acknowledges that “we” can’t just take these lessons (like we took everything else) – it is about making space for Indigenous lives and territories, making restitution for ongoing colonial impacts.

Like Edward Said’s Orientalism (1978) and Linda Tuhiwai-Smith’s Decolonising Methodologies (1999), The Other Side of Eden is paradigm-shifting.

Brody argues for a more balanced view of humanity. Hunting peoples do not seek to change their worlds to the extent that farmers do; they seek ways to make Country productive for all its inhabitants, human and otherwise.

All over the world, the territories of Indigenous peoples continue to map onto the regions of richest and most persistent biodiversity and intact ecosystems. That is not a coincidence, and Brody gives readers the tools to understand why.

Michael Adams is Honorary Principal Fellow in Human Geography at the University of Wollongong. He has received funding from several sources for research on Indigenous environmental relationships.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.