We remember home runs by who hit them… but there’s another player every bit as invested here. The act of giving up a home run can be every bit as emotional as the act of hitting one. And while bat flips, staredowns and similar acts of celebration receive far more attention, there is just as much to glean from the downcast gazes, muttered curse words and other expressions of misery from the men who make the aforementioned revelry possible.

That’s right: It’s time for the year in pitcher reactions to home runs. Or, as we called it last year, a study in the human condition. Here are some of the most memorable home runs of the season—and the pitchers who found themselves on the other side.

The One That Was Hit the Hardest

Game: Atlanta Braves at Los Angeles Dodgers on Sept. 2

Batter: Ronald Acuña, Jr.

Pitcher: Emmet Sheehan

This is a moment of limbo. The ball is still in the air here: Acuña is still tracking its path, still in the box, still holding the bat. The Dodgers fans behind the plate have not yet registered their disappointment. The umpire has not delivered his judgment. Nothing is set. There is no certainty visible here. Except in Sheehan, whose face betrays his distraught, bone-deep understanding that he has just given up a home run.

In a moment, the scoreboard will show that Acuña’s moonshot had an exit velocity of 121.2 mph, the hardest hit of the season. (It is in fact the hardest hit home run of the last three years.) Sheehan will not have to look to confirm that. He already knew.

The One That Flew the Furthest

Game: Arizona Diamondbacks at Los Angeles Angels on June 30

Batter: Shohei Ohtani

Pitcher: Tommy Henry

This was the week Ohtani put the finishing touches on one of the best months in modern baseball history. Everything he did felt magical—even, say, a solo shot in the latter innings of an obvious loss. This home run was so spectacular that context felt irrelevant. It traveled nearly 500 feet, rocketing to right field with complete, infallible authority. The broadcast cameras lingered afterward on Mike Trout, left slack-jawed in the on-deck circle, watching in visible awe.

Henry did not watch. The ball left the yard, the stadium erupting in cheers, but the pitcher did not direct his gaze upward. His eyes stayed trained on the mound below him, steadfast, moving on from this hitter and readying himself for the next one.

The One That Lit Up Playoff Trash Talk

Game: Atlanta Braves at Philadelphia Phillies on Oct. 11 (Game 3 of the NLDS)

Batter: Bryce Harper

Pitcher: Bryce Elder

Shortstop: Orlando Arcia

Within hours of this home run leaving the field, it was emblazoned on shirts and made the center of memes and litigated as a question of ethics in baseball journalism. But all of that, of course, focused on just two men: Harper, the hitter, and Arcia, the shortstop who received a fierce staredown during the journey around the bases. There was almost no attention paid to the pitcher who set the whole thing in motion in the first place: Elder.

He twisted to watch it. (A home run to the one guy you very much did not want to allow a home run to in this situation!) The ghost of his pitching stance hung in his posture as he saw it fly. He was a bit of a character here—an afterthought, really, written out of most of the tales of trash talk and revenge to come. But he felt it as acutely as anyone.

The One That Sealed the World Series

Game: Texas Rangers at Arizona Diamondbacks on Nov. 1 (World Series Game 5)

Batter: Marcus Semien

Pitcher: Paul Sewald

Almost everyone in this still image feels animated: Semien, bursting out of the box, the catcher and umpire, both straining to see the ball leave the yard. But Sewald is notably still. He does not turn to watch the ball, or twist in frustration, or do anything at all. For a moment—just a fraction of a second—he is the focal point of the broadcast. He is the one still, stable point, as a championship bursts into reach around him.

The One That Almost Wasn’t

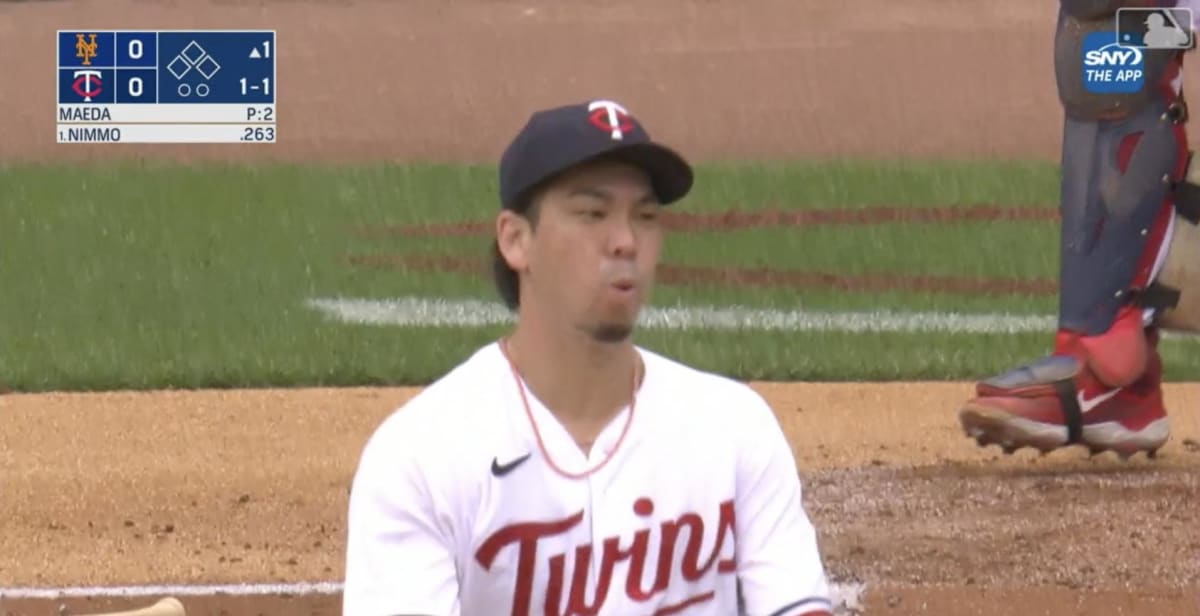

Game: New York Mets at Minnesota Twins on Sept. 9

Batter: Brandon Nimmo

Pitcher: Kenta Maeda

It might be useful context to know this one was juuuust out of reach at the wall for Twins left fielder Jordan Luplow. But do you really need to be told? Look at Maeda’s face. It’s all there.

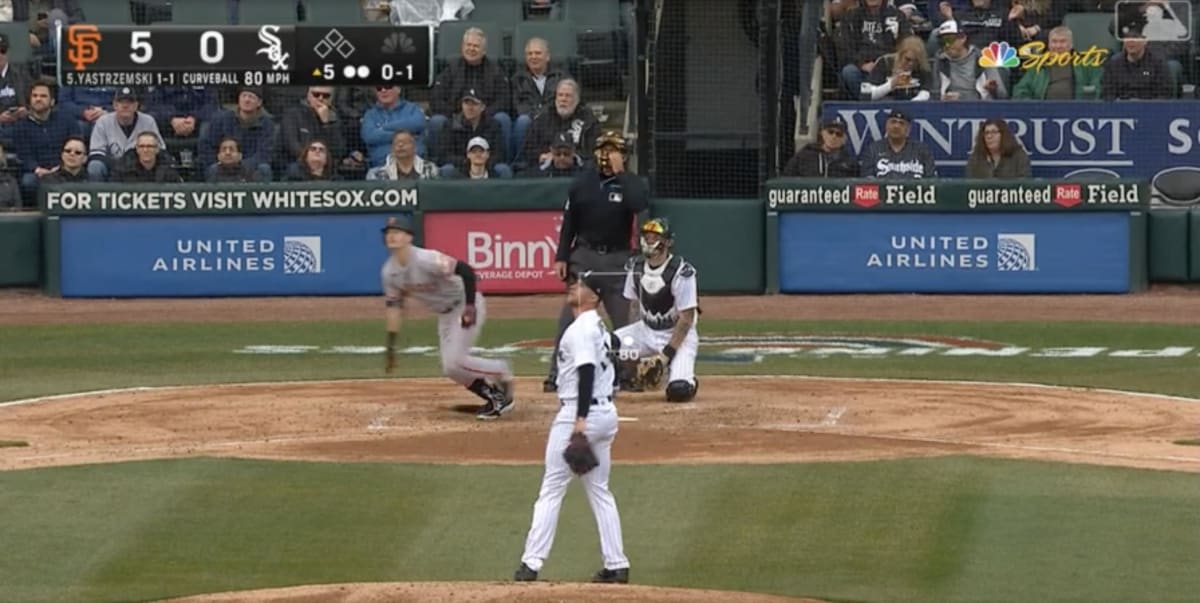

The Four That Came in One Inning

Game: San Francisco Giants at Chicago White Sox on April 3

Batters: Michael Conforto, Thairo Estrada, Mike Yazstremski, David Villar

Pitcher: Michael Kopech

Kopech and the White Sox were already down 3–0 when the fifth inning of this one started. And then Kopech gave up one home run, another, another and then one more. (The manager finally showed mercy and pulled him after that.) It was, obviously, a terrible inning. But it yielded a rich tapestry of reactions.

And here is the only one that looks truly painful. One home run? It happens to everybody. It’s an everyday irritation. Two home runs? It’s a problem. It’s maddening. It’s undignifying. It’s not fully out of control yet. This is not three home runs, or four—cartoonish numbers with no good explanation—and so there is nowhere else to turn. It’s Kopech, arms outstretched in exasperation, telling himself, Oh, come on.

When you’ve allowed two home runs in the space of five minutes—why turn to acknowledge a third?

Kopech, at last, has reached acceptance. There is no pain here. Only resignation.

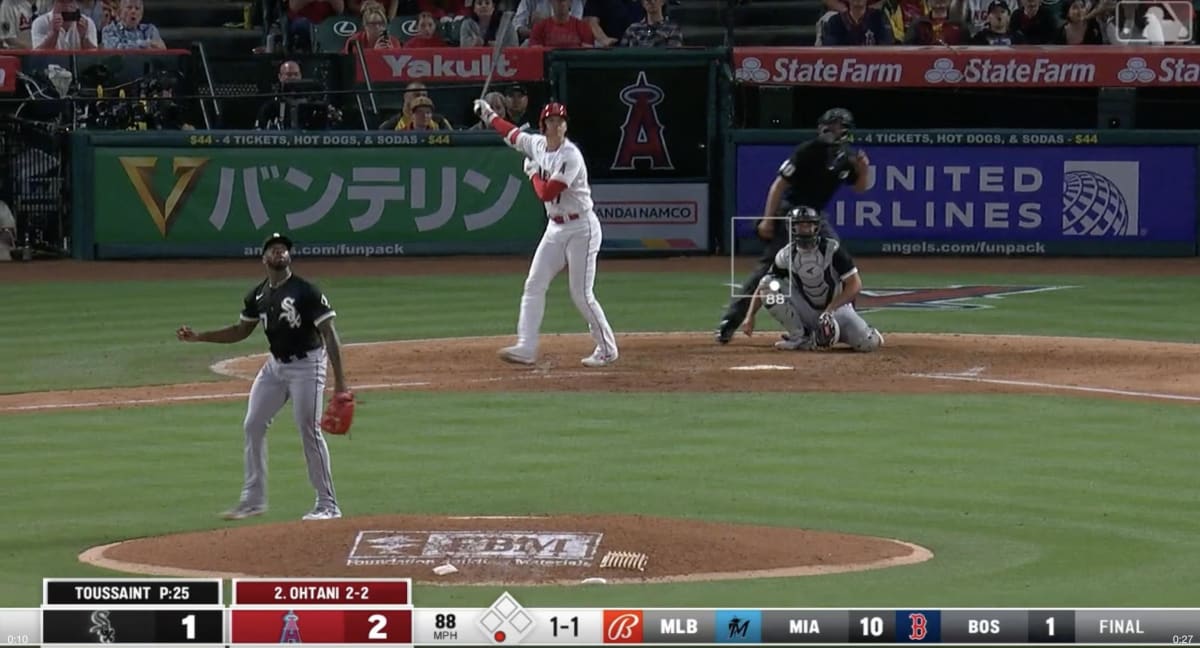

The One That Was an Ohtani Special

Game: Chicago White Sox at Los Angeles Angels on June 27

Batter: Shohei Ohtani

Pitcher: Touki Toussaint

On June 27, Ohtani pitched 6.1 innings of one-run ball with 10 strikeouts. He gave the Angels their first lead of the day with a home run in the second. But when he came to the plate in the bottom of the seventh, Angels ahead 2–1, it seemed he could use an insurance run to ensure the decision was a win. So he delivered it himself.

Toussaint just stared. It hadn’t been an especially bad pitch. But sometimes there’s nothing else you can do.

The One That Was My Favorite

Game: Los Angeles Angels at Colorado Rockies on June 24

Batter: Brenton Doyle

Pitcher: Kolton Ingram

No major league home run is pointless. They all mean something—a number for the back of the baseball card, at least, or evidence for an eventual arbitration case, even if they mean nothing for the game in question. But it’s hard to argue there was much of a meaning to this particular home run. It came in mid-June, the eighth inning of an Angels-Rockies, the home team down 25–0. Twenty-five! Nothing! Twenty-five to nothing! There were several home runs this year with a leverage index of 0.00—statistical evidence they came when nothing was at stake. This one felt the most pointless of all of them.

But it wasn’t pointless to Doyle, of course, a rookie who could still count his major league home runs on one hand when he hit this. And it certainly wasn’t pointless to Ingram, another rookie, who made just a handful of appearances this season. This game was out of hand; there was nothing to win or lose. Ingram entered in the seventh inning with the boat race already well-established. There was nothing he could do to either help or hurt his team in any significant way. He would’ve had to give up many, many, many home runs before one of them “meant” anything. Ingram gave up only the one. But look at his stance, his upturned gaze, his palpable frustration as he turns and watches it fly: This meant something. This meant so much.