When Treacle Walker was announced as a nominee for the 2022 Booker Prize, 87-year-old Alan Garner was highlighted as the oldest-ever shortlisted author. He is now 88. That said, Treacle Walker, begins with a quote from Italian quantum physicist, Carlo Rovelli: “Time is ignorance.”

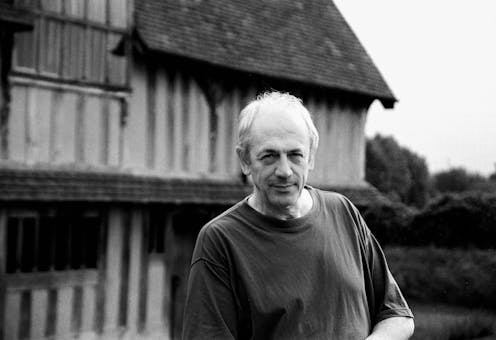

Age is, of course, an aspect of time. But Garner, older as he might be getting, has a photo of himself aged six (grinning very fully and twinkly-eyed at something distant), which he has stated most captures who he is “then and now”.

Describing why it had been nominated, the Booker committee described Treacle Walker as “fiction from a remarkable and enduring talent [that] brilliantly illuminates an introspective young mind trying to make sense of the world around him.” It is more than that, it is about how we take care of the Earth and understand it in relation to the universe. It feels to me, as a lifelong reader of Alan Garner, that this is where he has been leading us all along.

A boy in his own time

Treacle Walker features a modern improbability – a child who lives alone in their own house with nothing much other than marbles and comics to occupy him along with his travels into the landscape around Alderley Edge in Cheshire, Garner’s home turf. Joseph Coppock gets up when he hears the daily train, who he calls “Noony”, since it comes through when the sun is high.

That train is Joseph’s only time reference, aside from light and dark. How accurate that time is for those of us who live in a world dominated by the clock (the ones for whom the train runs perhaps) is irrelevant. Joseph’s world is drawn for us within the first page and Garner takes us quickly and quietly into this semi-timeless rural space.

In this space the reader accepts (well I did, immediately and without question) the strange outside-of-time life Joseph lives and the things that happen to him in the story. That Garner takes us so smoothly into this narrative demonstrates his level of craft.

Pace, compression and simplicity

In the frontispiece to Redshift, his sixth book, he describes his approach to writing as: “I must write poetry, making words work on more than one level, subjecting myself to the poetic disciplines – pace, compression, simplicity.” Those tools – pace, compression and simplicity – are what makes this seemingly impossible story work.

Garner is a long-established writer. He has won the children’s literary prize, the Carnegie Medal, twice, and the Guardian and Phoenix book prizes once each. He also has an OBE for his services to literature.

He is mostly identified as a children’s writer, although he has often been quoted as saying he sees himself as a general and much more inclusive writer.

His characters are usually, but not always, children. That is probably because children more easily question adults’ life-choices and can perhaps accept things that might challenge adult ideas of “commonsense”.

While we might decry those who work in book marketing as banal for attempting to pigeonhole his work in this way, I probably would not have read Ganer’s work as a child had they not done so. I don’t know where that would have left me as a reader, writer or general human.

Garner’s are “soul reading” texts that try to get to grips with the big things in life – such as landscape, geology, folk memory, life and death and the universe. However, the world we live in is a world of selling stuff, of “new, new, new” and how we find our way to the stories we really need is unpredictable, so I do bless the day that someone in a marketing department categorised the books so that they would be shelved where my mum would find them for me.

His first book The Weirdstone of Brisingamen was published in 1960. Treacle Walker is his 11th work of fiction. Not the most prolific of writers then. However, each of those books is crafted with care and there is not a wasted word in any of them. He is a poet’s novelist, interested in the aforementioned tools of pace, compression and simplicity.

Garner is also very much a writer of place. In his book of essays The Voice That Thunders (1997) his best advice to other writers is to “know your place”. By which, of course, he does not mean where you doff your cap, but develop your understanding of where you are and through that perhaps something of who you are.

He lives very close to where he was born and has lived in the area for most of his 88 years. But that doesn’t make his writing insular. To try to understand the ground beneath your feet and the sky above your head, wherever you find yourself, is to understand a bit more about the planet and ultimately the universe – and that would surely help even the most adrift of us to shut out the mayhem and get to grips a bit more with the question of who we are as animals, as co-occupants of the planet and the universe.

Treacle Walker is a book about that universe, about the universal, told through one small patch of land, and its keepers. If you haven’t read it – do so, I can’t see how you’d regret it.

Anna Robinson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.