The coffin was made of black wenge, a hardwood known for its resilience. Its journey began 10 days before on a grey street in Brussels. It was carried through the Belgian capital to a ceremony at a 16th-century palace, then driven to the Congolese embassy, to a public square for a viewing and, finally, to the airport. It was lifted on to a plane and flown across the Mediterranean to Tunis and on to the Democratic Republic of Congo, a distance of some 4,000 miles.

What made the casket unusual was not the length of its journey but what was inside: a single, gold-capped molar. It belonged to Patrice Lumumba, the anti-colonial hero, pan-African nationalist and the DRC’s first democratically elected prime minister, who was tortured and assassinated in 1961.

I saw the coffin on a late-June day in Kinshasa, as it neared its final destination. Escorted by a military band, it was carried through the grounds of L’Echangeur, a tower built in 1974 as a monument to Lumumba. The grounds were full of people, the atmosphere both solemn and celebratory. There were chants of “père de la patrie” (father of the nation) and “héros des opprimés” (hero of the oppressed). A group of Lumumba lookalikes wore tailored suits, thin ties and semi-rimless glasses, their hair neatly parted to one side. “Lumumba is the Jesus of Africa, we need to pray to him!” someone shouted from behind a fence.

“He is our father and, finally, after 61 years, we can mourn,” Juliana Amato Lumumba, his daughter, told me. “Bringing him back to his country of life, to his ancestors . . . that is important.” Government ministers and visiting dignitaries sat under the canopy of a huge Congolese flag and watched as a purpose-built mausoleum became the coffin’s last stop.

Patrice Émery Lumumba was 35 years old when he was killed by firing squad on January 17 1961. A tall, slim man with high cheekbones, he was a gifted orator who led his party, the Mouvement National Congolais, to victory in the DRC’s first elections after the country declared independence from Belgium in 1960. He had been prime minister for less than three months when he was deposed in a coup supported by the former colonial power and the US. A few months later, Lumumba was arrested, tortured and shot to death by political opponents in the hostile province of Katanga. His murder took place in the presence of Belgian officials.

Lumumba’s body and those of two colleagues who had been travelling with him, Joseph Okito and Maurice Mpolo, were never found. Decades later, a Belgian police commissioner in the Congo named Gerard Soete confessed that he and his brother had been given the job of disposing of the three bodies. They cut the corpses into pieces, according to a thinly fictionalised book Soete wrote in 1978, titled The Arena: the story of the death of Lumumba.

At the time of its publication, few seemed to realise it was based in fact. Soete had described the grisly scene in the third person, writing: “As soon as they put the bodies near the empty barrels and assemble their equipment, they realise that they are not prepared for that kind of job. They go back to the car and drink whisky . . . When he is left with only the torso and the head, he suddenly realises the horror of what he is doing . . . ”

Ludo De Witte, a Belgian sociologist who wrote a groundbreaking account of the murder and its causes decades later, explained that “the part of [Soete’s] book which recounts his exploits . . . should be read as authentic testimony”. Over lunch in Brussels, De Witte told me that Soete had confessed to him that he took Lumumba’s teeth as a trophy. In the book, Soete gave a different motive: “Here is the only material proof of the Prophet’s death. If a cult of martyrdom ever appeared, he could provide it with relics. He takes some pincers out of the tool bag, and extricates with difficulty two gold teeth from the Prophet’s upper jaw.”

Soete and his brother dissolved the rest of the body parts in vats of sulphuric acid that belonged to the Union Minière du Haut-Katanga, the company established by King Léopold II in 1906 to exploit the Congo’s mineral resources, whose profitability Belgium was so intent on protecting from Lumumba’s nationalist movement.

De Witte’s painstakingly researched book caused a furore on its publication in 1999, leading Belgium to set up a parliamentary inquiry into its responsibility for the killing. In a 2000 documentary, Soete admitted having two of Lumumba’s teeth but then said he had thrown them into the North Sea. He died that same year. During an interview with a Belgian magazine in 2015, his daughter showed one gold-capped tooth in a padded box. De Witte complained to the police, and Belgian authorities finally confiscated the tooth.

Four years later, Lumumba’s family were still waiting for restitution. In June 2020, at the height of the Black Lives Matter protests in the US, Lumumba’s daughter Juliana wrote to King Philippe of Belgium. “We, Lumumba’s children, call for the just return of the relics of Patrice Émery Lumumba to the land of his ancestors,” she wrote. “Why, after his terrible murder, have Lumumba’s remains been condemned to remain a soul forever wandering . . . used on the one hand as trophies by some of your fellow citizens, and on the other as funereal possessions sequestered by your kingdom’s judiciary?”

Three months later, a Belgian court finally cleared the way for the tooth to be returned to the DRC. The Covid-19 pandemic delayed the handover, but in 2022 the final stage of its journey began.

The day before the tooth was laid to rest in the mausoleum, it was taken in its casket to the Lumumba family residence in Gombe, an upmarket riverside district that is home to Kinshasa’s political elite and its embassies. As it was carried through the entrance, a choir of two dozen women sang: “Hear, hear, the promise we made to Lumumba, we want to keep it until today. We wonder about the death of Lumumba. Who ordered the death of Lumumba?”

A traditional chief named Konde Omekonga Lokolonga led a musical ceremony to welcome the tooth and to appease spirits that had been rattled by the murder. He wore a ceremonial leopard-skin cap and drummed an elondja, a tubular instrument, painted with leopard-like spots.

“I am very happy for the return of Lumumba since his soul, until now, was wandering here and there,” Lokolonga told me. “The spirits are happy because Lumumba’s relics have returned. The Congolese are happy as well.”

Lokolonga explained that in the Congolese spiritual tradition, a single part of a body — a nail, a clump of hair, a bone or tooth — could represent the whole person and that its burial would allow its soul to rest in peace. The people I spoke to rarely referred to it as la dent (the tooth), but rather as le corps (the body). Before arriving in Kinshasa, it had first travelled to Onalua, Lumumba’s birthplace, then to Kisangani, where he had worked as a civil servant and built his political profile, and then to Shilatembo, where he had been killed.

One of Lumumba’s grandchildren, Yema, a 30-year-old journalist, flew in from her home in the Netherlands. “We are Bantu. We transmit our history through symbols,” she said, as we sat in the garden of the family house. She was referring to the cluster of several ethno-linguistic groups that span vast parts of Africa. “All these funeral vigils that we have done all over the country are symbolic, but they also show that he’s come home, that his spirit can calm down and that it’s our turn, once we’ve buried him, to continue his path and his work.”

No DNA test had been carried out because it could have destroyed the tooth, Belgian officials said. “We have enough proof to say that it is, effectively, the tooth of Patrice Lumumba,” Eric Van Duyse, spokesman for the Belgian federal prosecutor’s office, told me in Brussels, citing a “clear line” of testimonies, including from Soete. “But we don’t have the DNA proof as, in consultation with the family, we decided not to do it.”

Roland Lumumba was two years old when his father was killed. In February 1961, his mother Pauline Opango marched through Léopoldville, now Kinshasa, with about 100 others to demand the return of her husband’s body for burial. She carried Roland in her arms. Today, he is president of the Patrice Lumumba Foundation, which works to preserve his father’s legacy through arts and culture. “The Belgians were responsible but were not alone on the ground,” he told me at the Congolese embassy in Brussels, where the casket was on display for the diaspora to pay tribute. “But the Belgians had the courage to say they were responsible. Now, if you want to know the whole truth, it goes on. It doesn’t end here today.”

Some Congolese believe that Lumumba was a marked man from the moment he made a speech on the day of the country’s independence, June 30 1960, at a ceremony in the Palais de la Nation, the building originally created as the residence of the colonial governor-general. The then-King Baudouin of Belgium spoke first, saying that the independence was the result of “the genius of King Léopold II”.

This reference to Léopold, who had ruled the Congo as his personal fiefdom and whose colonising of the country led to slavery, beheadings and the amputation of hands as punishments for workers, and an estimated 10 million deaths, was outrageous to many Congolese. The king went on to claim that for 80 years, Belgium had sent “the best of her sons” to the Congo and patronisingly added: “Don’t replace the structures that Belgium hands over to you until you are sure you can do better . . . It is your job, gentlemen, to show that we were right in trusting you.”

The king’s speech was followed by an uncontroversial address by the new Congolese president, Joseph Kasavubu. Then, despite no mention of it in the official programme, prime minister Lumumba took the stage. His words were a pointed rebuke to the condescension of the Belgian monarch: “Although this independence of the Congo is being proclaimed today by agreement with Belgium . . . no Congolese will ever forget that independence was won in struggle, a persevering and inspired struggle carried on from day to day . . . filled with tears, fire and blood. We are deeply proud of our struggle,” he continued, “because it was just and noble and indispensable in putting an end to the humiliating bondage forced upon us. That was our lot for the 80 years of colonial rule and our wounds are too fresh and much too painful to be forgotten.”

Lumumba’s address was met with a standing ovation. But it did not go down well with the king, the assembled Belgians or other western observers. A dispatch that ran in The Guardian was headlined “Marred”, and described King Baudouin behaving “with great dignity” despite “a speech by Lumumba, which can only be described as offensive”.

When the Belgian parliamentary inquiry reported its findings in 2001, it highlighted the speech as a moment that “confirmed the mutual distrust between Lumumba and the Belgian government, which undoubtedly influenced their reactions to the subsequent events”. It concluded that members of the Belgian government “and other Belgian figures” had “a moral responsibility in the circumstances which led to the death of Lumumba”, though it fell short of accepting any legal responsibility.

Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja, a Congolese historian, Lumumba biographer and Congo’s UN ambassador, argues that, even now, Belgium has not fully acknowledged its role. “They are the ones, alongside the United States, that plotted it,” he told me. “The United States has a very short, weak memory, and 1961 is too far behind us now.”

Multiple archival documents testify to the American government’s desire to get rid of Lumumba at the time. In August 1960, the head of the CIA, Allen Dulles, telegrammed his station chief in Léopoldville: “If [Lumumba] continues to hold high office, the inevitable result will at best be chaos and at worst pave the way to Communist takeover of the Congo with disastrous consequences for the prestige of UN and for the interests of the free world generally . . . His removal must be an urgent and prime objective and that under existing conditions this should be a high priority of our covert action.”

In the days after Congo became independent, a mutiny began in the force publique, the country’s armed forces, which consisted of some 25,000 underpaid Congolese soldiers overseen by a thousand Belgian officers. Lumumba tried to placate the army by removing senior officers and allowing the so-called Africanisation of the leadership corps. But events ran away from him. As soldiers rebelled in different parts of the Congo, some murdered and raped Belgian citizens. The Belgian government decided to intervene militarily and reoccupy parts of its former colony.

It also supported the secession of Katanga, the mineral-rich province where the Union Minière du Haut-Katanga was based and the source of much of Belgium’s wealth. In response, Lumumba and Kasavubu sent a telegram requesting urgent military help from the UN. “Consider unsolicited Belgian operation as act of aggression against our country,” they wrote. “Accuse Belgian government of detailed preparation of Katangan secession to retain grip on our country.”

The UN agreed to send a peacekeeping force but declined to intervene in Katanga. Lumumba sent a second desperate message, this time to Moscow: “Could be induced to request intervention by Soviet Union if western camp does not terminate act of aggression against sovereignty . . . lives of president of republic and prime minister in danger.”

The historian David Van Reybrouck says that this telegram, “in a single swoop, opened a new front in the cold war”. Western officials worried that through Lumumba, the Soviet Union would gain a foothold in central Africa, as well as access to mineral resources including uranium. Rather than the independence day speech, it may have been this telegram that ultimately became Lumumba’s death warrant. “Lumumba was a nationalist, yes. A pan-Africanist, yes. Someone with social consciousness who wanted an independent Congo, yes. But he was not a communist,” Jean Omasombo Tshonda, a political scientist at the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Belgium, told me. “He was trying to make independent Congo work at a time of trouble.”

Lumumba’s assassination sparked demonstrations in London, Belgrade, Cairo, Moscow and New Delhi. Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru called it “an international crime of the first magnitude”. Ghana’s independence hero and the father of African nationalism, Kwame Nkrumah, slammed the UN for not intervening: “The first time in history that the legal ruler of a country has been done to death with the open connivance of a world organisation.” Later, the Argentine-Cuban revolutionary, Ernesto “Che” Guevara, decried the assassination in a fiery speech before the UN.

It is impossible to know what kind of prime minister Lumumba would have been if he had not been ousted, or how he would have changed the Congo if he had not been killed. But it is hard to imagine he could have been worse than the man who received the support of Belgium and the US: Joseph-Désiré Mobutu. He took power in a coup in 1965, renamed himself Mobutu Sese Seko, renamed the country Zaire, and ruled as a dictator for 32 years. His kleptocratic regime looted the state for decades.

The president of Congo works from a modernist compound at the crest of a hill on the outskirts of Kinshasa that overlooks the Congo river. Félix Tshisekedi is a burly man with rimless glasses, who speaks confidently, frequently punctuating his sentences with a smile. Dressed in brown slacks and a relaxed grey-blue jacket, he sat on a cream leather sofa between two shiny blue and yellow cushions. “He is a true icon,” Tshisekedi said of Lumumba. “Despite the many generations that came and went, and this is the third generation since Lumumba, he is still regarded as an icon.”

Tshisekedi understood the power of the moment Lumumba’s tooth finally came home. The government had put a Congolese film-maker, Balufu Bakupa-Kanyinda, in charge of organising the celebrations. In the week of the burial, the flags on government buildings were flown at half mast and the capital was plastered with billboards thanking the héros national. At the ceremony, Tshisekedi told the assembled crowd that the country was finally able to end the period of mourning that had begun 61 years before.

Not everyone was happy about Lumumba’s legacy being used by politicians from other parties. Joseph Anganda, a senior member of Lumumba’s party, believes that Congolese governments, starting with Mobutu and continuing with Tshisekedi, have taken advantage of Lumumba’s story. “People are not sufficiently informed about the truth,” he told me. “The government is trying to get things on its side, but Félix Tshisekedi comes from political tendencies that are opposed to the style and policies of Patrice Lumumba.”

Tshisekedi took office in 2019, after it was announced that he had won the presidential election. But opposition politicians and the Catholic Church immediately questioned the result. The church issued a statement saying the result did not correspond with the data from its tens of thousands of observers monitoring the vote. FT analysis of two separate collections of voting data showed that his opponent Martin Fayulu was the clear winner. Tshisekedi has repeatedly denied fraud. Presidential elections are due to be held in December this year, and some analysts consider it likely that he will win, this time probably legitimately.

As I stood on a balcony overlooking Lumumba’s casket in Kinshasa’s Palais de la Nation, Marie Misamu Bakala, a 62-year-old janitor, squeezed herself through the door, in between dignitaries, to be able to see “papa Lumumba” for the first and last time. She was only a year old when he was killed, but remembered her parents speaking fondly of him. She broke into tears. “Papa is home, finally,” she whispered. “It has been too long.” “There’s a historic trauma among many Congolese today,” Mona Pembele, a Congolese-Belgian activist, told me. Many of the older people I spoke to felt anger or grief. The intervention in their country’s nascent democracy, the brutal treatment of their elected prime minister, occurred within living memory.

In Brussels, several weeks earlier, I had spoken to a nurse, Tima Kamba, who had moved to Belgium from the Congo as a child. She had come to wave goodbye to the casket at Place Patrice Lumumba, the square named in his honour. “After 60 years, the Belgian government says it has a moral responsibility. But the Belgian government has been involved in the death of papa Lumumba from the beginning till the end. Moral responsibility?” She was incredulous. “The Congolese love the Belgians, but Belgium does not know how to love the Congolese. All because there is a historical problem. They don’t know how to love us because they have our blood on their hands.”

The Congolese writer In Koli Jean Bofane, who has lived in Belgium since 1993, felt the ceremonies around the tooth’s return should not disguise the horror of its history. “The whole thing is macabre,” he said, as we drank Congolese beer and ate grilled plantains in Brussels’ African quarter, Matonge. “Imagine that the assassins of John Fitzgerald Kennedy come to tell you how they killed him and kept a tooth or a finger. How would Americans feel?” On a street corner near the restaurant, Congolese-Belgian artists had put up a big papier-mâché replica of the tooth.

Lumumba believed in democracy and the rule of law. In a letter smuggled out of the cell in which he was kept in the final days before his death, he wrote with desperate clarity: “The penal code in effect in the Congo expressly stipulates the prisoner must be taken before the examining magistrate investigating the charges on the day following his arrest at the very latest . . . Whatever the circumstances, the prisoner is entitled to a lawyer . . . No warrant for our arrest has been served. We have simply been kept in an army camp for thirty-four days, in punishment cells.”

Nobody with power listened. No lawyers came. As De Witte recounts in his book, an ally of Lumumba tried to give the letter to the UN secretary-general, Dag Hammarskjöld, who was visiting the DRC at the time. Hammarskjöld, a Swede, reportedly turned red and asked that it be given to his private secretary. Just five months earlier, Hammarskjöld had told a US representative at the UN that he believed the “situation in Congo would not be straightened out until Lumumba was dealt with” and that Lumumba must be “broken”.

The tooth’s return has reopened the debate over what exactly Belgium owes to Congo and what other colonial powers owe to their former colonies. The Royal Museum for Central Africa outside Brussels contains some 84,000 objects; in February last year, it gave a list of its inventory to the DRC to allow for an investigation into their provenance. “This is bigger than a tooth,” Amory Lumumba, another grandchild, told me over jambon-fromage at a bakery in Kinshasa. “It is about what it represents.”

Yet the tooth also had a specific power of its own. It spent decades hidden in a foreign land, the trophy of a man who brutalised and dismembered its owner. Its grim existence proved something about Belgium’s colonial history that the country’s institutions had worked to forget. In Brussels, Alexander De Croo, Belgium’s prime minister, spoke candidly about the contradiction between the humane democracy he hoped to represent and the reality of the Belgian government’s actions six decades ago. In a speech before Lumumba’s family at the Palais d’Egmont, he said: “A man was assassinated for his political convictions, his words, his ideals. For the democrat that I am, it is indefensible. For the liberal that I am, it is unacceptable. And for the human that I am, it is odious.”

Today, the DRC remains one of the poorest countries in the world, damaged by corruption, decades of kleptocratic government and rebel militia groups. Yet its mineral deposits — it is Africa’s largest copper producer and the source of half of the world’s cobalt — continue to attract the interest of private companies, militias and nation states, including China. The Kinshasa mausoleum in which the tooth now lies, which reportedly cost $2.4mn, was built by a Chinese company. Above it is a cast bronze statue of Lumumba that was erected in 2002 by a North Korean state-controlled construction company.

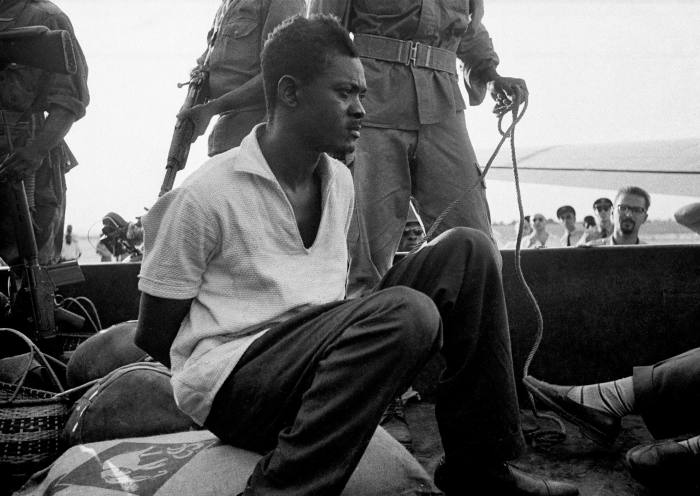

Unlike the Lumumba who was caught on film just after his final arrest — a cowed, beaten man in a short-sleeved shirt, whose beard had been shorn, whose eyes are glazed over with pain and dread — this version of the country’s first prime minister looks proudly over the capital city, his suit jacket buttoned, his expression firm and determined. One of his hands is raised, as if in greeting, or farewell.

Andres Schipani is the FT’s east and central Africa bureau chief

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first