by Joshua Ferris (2007)

Ferris’s novel is a hilarious ode to ergonomic chairs, watercooler gossip and “the great unsung pastime of American corporate life, the wadded paper toss”. By telling the story in the first person plural, the author slyly asks whether modern corporate culture leaves any room for the individual: “We liked wasting time, but almost nothing was more annoying than having our wasted time wasted on something not worth wasting it on…” The collective narrator is withering: “A small, angry book about work... Now there was a fun read on the beach.” Photograph: Public Domain

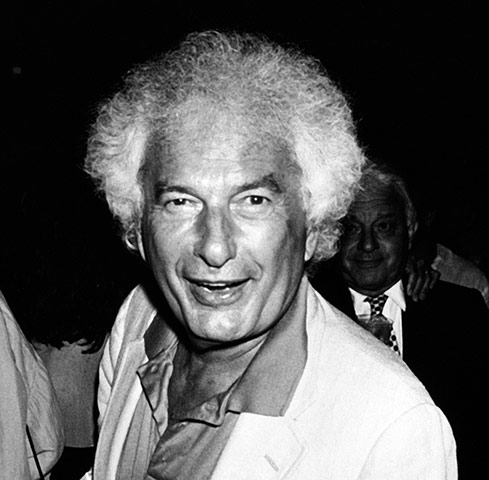

by Joseph Heller (1974)

Bob Slocum, a promising executive, delivers the monologue it took Heller 12 years to write. This is comedy at its blackest, full of jokes which bring no joy. Kurt Vonnegut, with barely disguised admiration, called it “one of the unhappiest books ever written”. Heller suggests that dysfunctionality in the office can create ripples of contagion which reach beyond its walls. “The world just doesn’t work,” he tells us, deadpan. “It’s an idea whose time is gone.” A bleaker, slower read than Catch-22, but a masterful novel nonetheless. Photograph: WireImage/Getty Images

by Don DeLillo (1971)

The novel from which Ferris’s book takes its title and much of its tone, DeLillo’s 1971 debut follows the fortunes of arrogant, amusing 28-year-old TV exec David Bell, a compulsive flirt who is constantly strategising about how to get ahead in the office. “One sought to avoid categories,” he tells us. “To be neither handsome nor unattractive, neither ruthless nor clever, was to be considered a hero by the bland [and] a nice fellow by the brilliant.” Full of biting irony and insight, the book still feels fresh in its evocation of the way we work. Photograph: Public Domain

produced and directed by Billy Wilder (1960)

An Oscar-winning fable of workplace conflict in which ambitious paper-pusher CC Baxter, played by Jack Lemmon, climbs the corporate ladder by allowing senior management to use his apartment for extramarital encounters. Funny, melancholy, sentimental – this is the story of an employee who finds his way up to the prestigious 27th floor only to decide he was better off downstairs. Shirley MacLaine is lovely as the elevator operator who’s a “bad insurance risk” when it comes to men. Photograph: Allstar

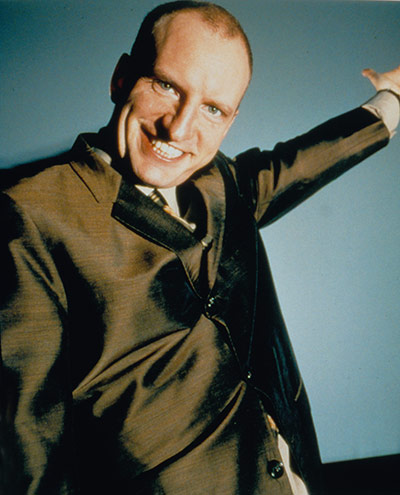

directed by Steven Soderbergh (1996)

The hero of Stephen Soderbergh’s dark, dream-like film is Fletcher Munson, a disillusioned office worker who finds it hard to focus on anything except the “masturbation breaks” he takes in the company bathrooms. Sitting on the toilet, getting the task done, his eyes remain fixed on his wristwatch. Is he stressed about getting back to his desk, or has corporate America’s fetish for deadlines made timekeeping a turn-on? Soderbergh called the film an “artistic wake-up call” to himself. Photograph: BFI

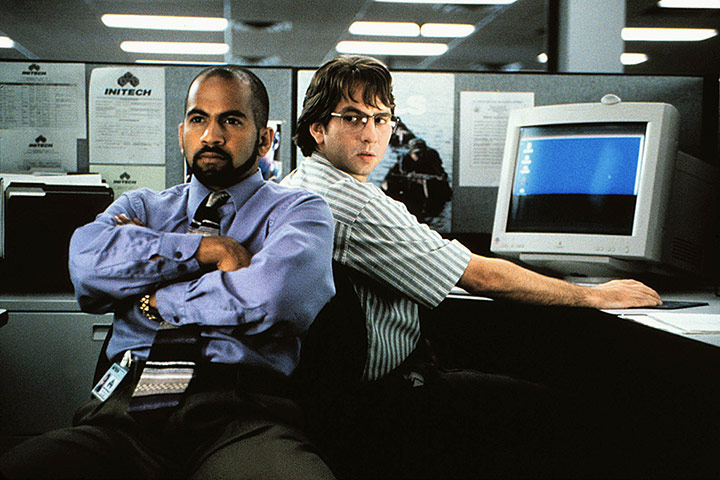

directed by Mike Judge (1999)After a visit to an occupational hypnotherapist, depressed software programmer Peter Gibbons has a bright idea. If something at work gets him down, why not just remove it? He starts with a particularly unpleasant door handle and progresses to corporate banners. Before long, he’s knocking down partition walls to get a better view of the window. There’s a great scene in which an employee tells Gibbons, at length, about the absolutely essential need to put “cover sheets on all TPS reports”. All this silliness is a welcome relief from the fact that, as the movie’s tagline puts it, “Work Sucks”.

Photograph: Allstar

directed by Steve McQueen (2011)

Michael Fassbender plays the ultimate pleasure-seeking executive, a man lethally committed to one-night stands, prostitutes and pornography. McQueen’s long takes force the viewer to share in the central character’s voyeurism – we’re there with him in the office kitchen as he flirts with a colleague, and we’re with him again on his morning commute, locking eyes with anyone who’ll meet his gaze, desperately seeking a new stranger to screw. The film in which Fassbender, famous for his trademark clenched jaw, added clenched buttocks to his repertoire. Photograph: Rex Features

created and produced by Matthew Weiner (2007-)

On the small screen, offices are often motifs for anonymity and banality. So thank God for Mad Men, which gives the fictional workplace an almighty revamp via liberal close-ups of whiskey tumblers, slick 60s decor, Don Draper’s face and the staggeringly pneumatic Joan Holloway. Draper is an interesting twist on the classic office drone; he’s only truly alive when at work. But it’s Roger Sterling who gets all the best lines. “Who knows why people in history did good things?” he asks. “For all we know Jesus was trying to get the loaves and fishes account.”

Photograph: Allstar

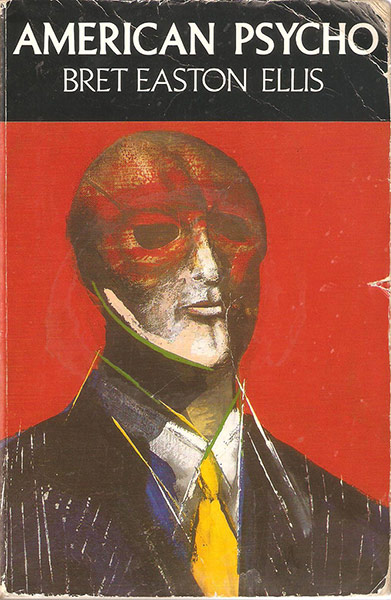

by Bret Easton Ellis (1991)

Take Shame, add Huey Lewis and a chainsaw, and you’ve got Bret Easton Ellis’s seminal 1991 novel and its eventual film adaptation. The sight of a severed head fails to make Patrick Bateman blink, but a glimpse of a rival’s business card – a thing of “subtle off-white” beauty boasting “tasteful thickness” and a flawless watermark – makes him instantly feverish. Is he a lone psychopath, or the inevitable product of a company which cares more about its stationery supplies than its people? Meat cleavers, nail guns, axes, knives… Bateman’s main creative outlet is his choice of weapon. Photograph: Public Domain

created by Ricky Gervais and Stephen Merchant (2001-03)

It’s hard now to imagine a time when you could speak about a day in “the office” without bringing to mind the sad, funny, hypnotically hideous character of David Brent. Renaissance man, maverick, philosopher, musician – and, first and foremost, general manager at Wernham Hogg paper merchants. A TV series that celebrates office life in all its cringing, toe-curling glory.

Photograph: Public Domain