Franco Harris left plenty of plays for people to pick from, and most, in remembering him, would probably choose the one he made as a rookie on Dec. 23, 1972, in Pittsburgh.

But that’s not the one Terry Bradshaw wanted to talk about Wednesday morning.

His was 93 tackle trap. Bradshaw actually called it personally, because that’s how it worked with quarterbacks in those days. And like the Immaculate Reception, it ended with Harris crossing the goal line in a Steelers playoff win—this one for the franchise’s third championship in Super Bowl XIII.

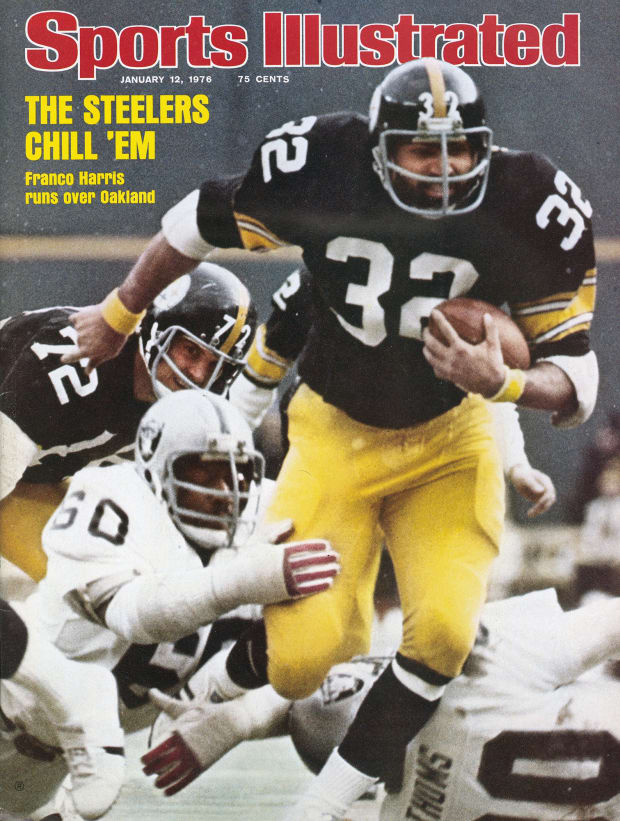

Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated

Harris died at 72 years old overnight Wednesday. He’ll be remembered as one of the iconic figures of the great Steelers dynasty of the 1970s. To those who played on those teams, though, more than being remembered as a great player, which he was, he’ll be remembered as an even greater teammate. Which is why 93 tackle trap is the play that was etched in Bradshaw’s mind as he tried to memorialize his great friend.

Just before that play call—after Bradshaw had taken another hit—Harris saw the Cowboys taking what had become a chippy game between the great rivals of the era to another level. It was time for the Steelers’ 6'2", 230-pound bellcow to do something about it.

“He thought that they had roughed me up too much when they got me down and he was steaming,” Bradshaw said, from his home in Louisiana. “He was one of the vocal guys, in a good way. His leadership was never pointed with anger. It was always a positive leadership quality that he had. It was a good one. And he came into the huddle, and I was getting back to the huddle, getting ready to call a play, and he didn’t call me TB, he called me Brad.

“And he goes, Brad—he was so mad—let me have the ball.”

Bradshaw called it in the huddle: 93 tackle trap. And as the Steelers lined up, Bradshaw saw Dallas safeties Charlie Waters and Cliff Harris shift over and then creep up into the box, seemingly giving away a blitz look that the call would easily exploit.

“As I’m walking up, I’m going, Oh my gosh. The perfect play,” Bradshaw says, laughing. “Well, it wasn’t a blitz. Here’s what happened—I went on the quick count, they didn’t have time to get back in position, and ended up running into the umpire. Back then, the umpire was on the other side behind the linebacker in the middle. And they ran into the umpire, which blocked for Franco, and he goes 22 yards for the touchdown.

“You go back and look at that play and you’ll see it. And that was Franco’s play. He wanted the football because he thought I got roughed up. That’s just one example [of who he was].”

O.K., now here’s the play:

The other thing Harris was, besides a Hall of Fame teammate: a Hall of Fame player. And that particular play showed it, too.

“The greatness of Franco was because [he matched] our offensive line and the quickness that we had,” Bradshaw says. “We were a trapping team. We were a zone-blocking team, whatever you want to call it, and Franco had to find the holes, but you had to be quick enough to run that offense, the fullbacks did. So he really wasn’t a fullback. He was a tailback playing fullback.”

Which—blended with a 230-pound frame and rough-and-tumble mindset, in an era when running back was football’s Hollywood position—made him the perfect embodiment of a dominant blue-collar team playing in a blue-collar city, and set him up to compile a list of accomplishments that ran as long as he could in the open field.

• He was the NFL’s Offensive Rookie of the Year for what he did in the regular season ahead of the Immaculate Reception, which, by the way, was the first playoff touchdown in Steelers history and led to the franchise’s first playoff win.

• He made the Pro Bowl in each of his first nine years in the NFL, garnering first-team All-Pro honors once (1977) and second-team All-Pro honors twice (’72, ’75).

• He led the NFL in rushing touchdowns with 14 in 1976 and rushed for more than 1,000 yards eight times, with the first five of those coming before the NFL went from a 14-game season to 16 games.

• He retired in 1984, after a final year with the Seahawks that followed 12 as a Steeler, with 12,120 career yards rushing. That put him third at the time, behind only Walter Payton and Jim Brown. He’s still 15th on the list.

• He was a second-team NFL All-Decade selection for the 1970s, and a first-ballot Pro Football Hall of Famer.

And to the guy Bradshaw wanted to remember on Wednesday morning, Harris was named NFL Man of the Year in 1976. Which, obviously, is a big reason so many Steelers were struggling with the news on Wednesday morning.

Walter Iooss Jr./Sports Illustrated

All you have to do to understand what Harris meant to the people of western Pennsylvania is deplane at the Pittsburgh International Airport. There, at the crossroads of the airport’s terminals, is a statue of the Steelers legend picking the ball off the turf as he did making the Immaculate Reception, one that stands next to a statue of George Washington.

Over the top? Maybe a little.

But Harris really did stand out, even among a 1970s crew that won four Super Bowls in six years for a franchise that had previously been a laughingstock, and produced an absolutely staggering 12 Hall of Famers among its players, coaches and scouts.

So, yes, this one hit hard. Bradshaw got the news from his wife, Tammy, on Wednesday morning, with Tammy having gotten a text to inform them at 3 a.m. Central from another Steelers Hall of Famer, Mel Blount. Making it even tougher for Bradshaw to grapple with was the fact that the two were together in Los Angeles just a few weeks ago to shoot a show on the Immaculate Reception, ahead of Saturday night's game between the Steelers and Raiders, which will commemorate its 50th anniversary.

“The play is 50 years old Friday, and they’re gonna retire his number at halftime against the Raiders [on Saturday],” Bradshaw says. “Man, how does that line up? Right? How do you line that up? I just can’t quite put that together right now. As a Christian, I’m going, O.K., but how does God just say ‘O.K., time for you to join your other fellow Steeler teammates in heaven’?

“It won’t be long; we’ll have the whole bunch of us up there, you know?”

Bradshaw said he and Harris tried to make sure to catch up two or three times a year—“At least once, always”—and he remembered one more recent time when Harris asked him whether he eats blueberries. Bradshaw was a little confused but responded that, sure, he liked blueberries.

Brad, you gotta eat blueberries, Harris said. I eat tons of blueberries. They’re brain food. They help you remember.

Bradshaw shot back, laughing, You’re eating blueberries, but you’re selling donuts to these kids in elementary school? What kind of deal is that?

It was true, of course, that Harris was selling donuts—the Super Donut is a specialty at his Super Bakery food-service enterprise in Pittsburgh. And it was also true that there was so much that he had, and his teammates had, to remember from those glory days of a half-century ago.

Along those lines, while he talked, Bradshaw had Tammy go grab the No. 32 jersey that Harris presented him with a picture with the No. 50 on it. “And the 50 right in the middle,” Bradshaw says, “is a dark shadow of him bending over, catching the football.” As Harris gave him the mementos, Bradshaw smiled and told his friend he wouldn’t take the jersey unless Harris signed. So Harris grabbed a marker and scrawled his name.

“So there’s his signature right there. We’re having it framed,” Bradshaw says. “Obviously, I was gonna treasure it anyway, but now more so than ever, since he passed away.”

Then, there was the other thing the old quarterback remembered about the last time he saw the fullback who always—in the Super Bowl or otherwise—had his back.

“I remember kissing him on the cheek in L.A. and whispering in his ear, I love you, man,” Bradshaw says. “And he said, I love you too, Brad. … My relationship with him was very personal. And when we say great teammate, come on, that sums it up, man. Everybody’s going to say the same thing when you talk to them.”

Much of Pittsburgh would, too. And for good reason.