The only reason Yuri Parfenov was not murdered in the 1941 massacre of Odesa’s Jewish population is because a family hid him and his brother in a toilet pit when the soldiers came for them.

The son of a Jewish mother and a Russian father, Mr Parfenov says he was due to be taken to the neighbouring region of Mykolaiv and shot that day.

In total, 14 members of his family – including his mother – were killed during the Holocaust in Ukraine. In the Black Sea port city of Odesa, tens of thousands of Jewish residents were shot, burned alive, and worked or starved to death – predominantly by Romanian soldiers allied with Nazi Germany.

But Yuri survived, and later went on to serve in the army of the Soviet Union.

And so, he says, it is particularly ironic that as a half-Russian Holocaust survivor and former USSR tank captain, he faces death again, but this time at the hands of Vladimir Putin, who claims his invasion is intended to “denazify” the country and save the Russian-speaking inhabitants of Ukraine from “genocide”.

“Tell Putin: who are you liberating us from?” Yuri says in Russian – his native tongue – while shaking with rage.

“I have no words; he is a monster. We didn’t ask for anyone to invade our land, to ‘liberate’ us, to kill our children.

“I want to tell Putin face to face, ‘You are a murderer.’ I cannot believe I have lived to see a war which could evolve into World War Three.”

Yuri is one of dozens of Holocaust survivors living in Odesa, which has a large Russian-speaking community and is steeped in a rich but painful Jewish history going back to its founding by Catherine the Great in 1794.

Sitting in the 100-year-old Chabad synagogue in the city centre, Roman Shvarcman, 88, another Holocaust survivor, who runs an association representing Jewish former prisoners of Nazi ghettos and concentration camps, crumples into tears.

Last month he nearly died from Covid, only to face the threat of death once more as his strategically placed hometown awaits an amphibious, ground and air assault by Russia.

“When the air raid sirens scream, I try to make it to the basement of my 10-storey building, and I sit in the cold and pray that my grandchildren, my great grandchildren, will have a bright and happy youth,” he tells The Independent.

“We are a generation of people who lost their childhood. I do not worry about myself, I worry about the next generation.”

Yuri compares Mr Putin to Adolf Hitler, saying Ukraine is facing mass slaughter again.

“During the Second World War, the Nazis tried to kill all the Jews. And now Russians are trying to kill every Ukrainian. Ukraine is my land. I am not going to leave this country, even if they kill me. I will not run.”

President Putin has claimed that the aim of his invasion is to “denazify” Ukraine and halt the “genocide” of its Russian-speaking population.

Ukraine, a democratic country, does have a far-right movement affiliated with armed groups including nationalist militia the Azov battalion. But right-wing extremists have lost ground in recent elections and enjoy far less support nationally than similar parties in other parts of Europe.

Mr Putin, meanwhile, has come under fire for actually damaging Jewish monuments.

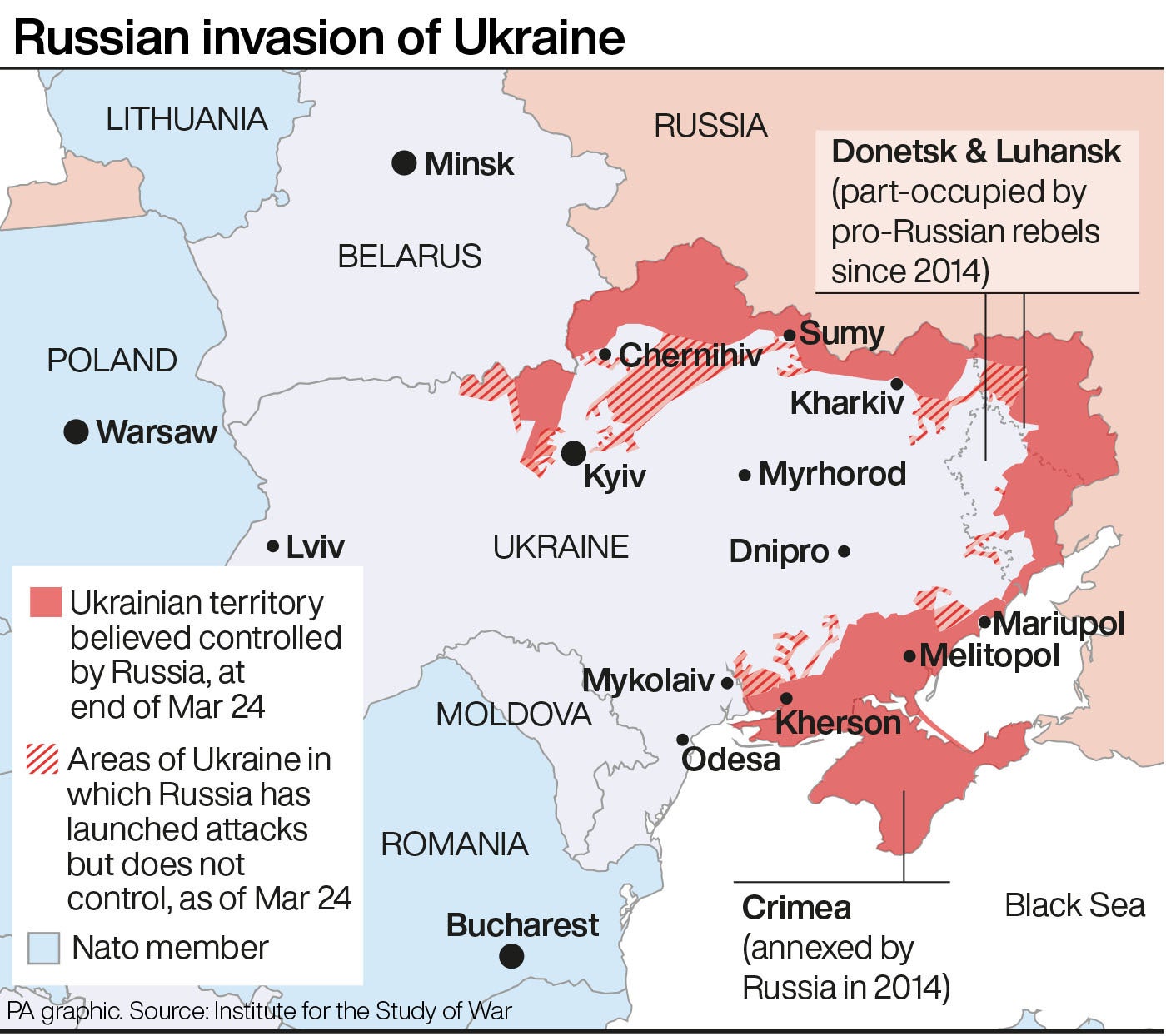

Just a few days ago, the British ambassador to Ukraine, Melinda Simmons, tweeted that a Holocaust memorial near to the eastern city of Kharkiv had been damaged in the bombardment. She posted a photo of the wrecked menorah monument at the Drobitsky Yar site, where 11,000 Jews were killed by Nazis in a ravine.

In the first week of the war, Ukraine reported that the Babyn Yar Holocaust memorial site in Kyiv – where more than 30,000 Jews were slaughtered by Nazi Germany – had also come close to being hit by Russian airstrikes. Odesa fears it is next.

The “Pearl of the Black Sea” is a key supply line and strategic gateway to the rest of Ukraine, and so has long been in the sights of the Russians, who are heavily shelling, besieging and even occupying towns further east along the coast.

Odesa has a long and difficult Jewish history. It was originally located in the Pale of Settlement, the part of the Russian empire in which Jews were permitted to live. The community suffered in the pogroms of the early 20th century, but by the 1930s around 200,000 Jews lived in the coastal city, making up around a third of the total population.

That changed with the advent of the Second World War. Only half of the Jewish population of Odesa managed to escape before Germany’s Romanian allies entered parts of the Soviet territories and occupied the city.

More than 25,000 Jews were murdered in the ensuing onslaught, and an estimated 60,000 others were deported, with most perishing in camps and ghettos. Jewish civilians were locked in warehouses, doused in petrol, and burned alive.

The stories that Yuri and Roman tell of that time are chilling, and in many ways feel horribly familiar in the current conflict.

Roman’s family, originally from Vinnytsia, a city 400km (250 miles) north, fled in a convoy of civilians, which came under repeated heavy bombing before eventually being stopped by German soldiers and forced to turn around. His family were starved, he says; his sister was raped by Romanian soldiers; and his older brother was shot on a bombed-out bridge. Soldiers ripped Yuri from his mother’s arms, and shot her when she tried to take her child back.

We are a generation of people who lost their childhood. I do not worry about myself, I worry about the next generation

Those horrors have been laid to rest recently. In 2018, a special memorial event was attended by German and Romanian ambassadors to properly mark the largely forgotten 1941-42 massacres in Odesa, which Yuri and Roman survived.

But over the last few years there has also been something of a renaissance for the community, says Rabbi Avraham Wolff, the chief rabbi of Odesa and southern Ukraine, who runs the Chabad synagogue there.

Before the latest invasion, according to Rabbi Wolff, 35,000 Jewish people were among the million residents of the city.

His community runs two Jewish kindergartens, two schools, two orphanages, a Jewish university, and a nursing home for 50 Holocaust survivors: an extensive network that the rabbi says means that out of all the places in the world, he felt the most safe in southern Ukraine.

“I wish every rabbi in the world would have the same freedom which I enjoy here. We have 11 buildings in this city, anything we need the city provides,” he says from his office next to the synagogue.

“There are only two countries in the world where at one time the prime minister and president were both Jewish – that is Israel and Ukraine,” he adds, referring to Jewish president Volodymyr Zelensky and his former prime minister Volodymyr Groysman. “But [the idea that] I need someone to set me free? It’s fantastic[al] to talk about Nazism here. It has nothing to do with the true reality on the ground.”

Rabbi Wolff says his biggest concern right now is actually the dismantling of the community he has worked hard to build.

He and his teams of volunteers have organised the evacuation of nearly 6,000 Jewish and non-Jewish residents of Odesa to neighbouring countries since the war began. He also evacuated 120 children from his orphanages to Germany, as well as several hundred other women and children from the city, despite the fact that most had no travel documents.

He cannot move the 50 Holocaust survivors in the nursing home he runs, as they are too old and frail and would be unlikely to survive the journey out of Ukraine. All he can do is stock up on supplies like canned food, pasta and rice, and pay the carers three months’ salary up front to watch over them. They pray the worst does not happen.

“It is very painful what is going on for the Jewish community here. For the last few years we have collected 35,000 people – 35,000 pieces of the puzzle – into one big picture. We built institutions, from kindergartens to nursing homes, from orphanages to a Jewish university.

“We made this picture, and then we framed it and we put it on the wall. But now it is falling down. Thirty-five thousand pieces of a puzzle scattered across Ukraine, Moldova, Germany and Israel. It is broken,” Rabbi Wolff adds.

“We are still here, we are working, but it is not the same.”

For Yuri and Roman, their focus is their children and their grandchildren, and protecting them from the horrors they grew up with. They both vow to stay in the city no matter what.

“I can’t hold a rifle, I am not a fighter and I am too old, but my weapon is my words against this Russian fascism. It is my weapon to fight,” Roman says in tears.

Yuri, a few years younger, says he is prepared to join the territorial defence. “If needed I am ready to defend the city with a gun,” he says, as the afternoon sun slides down a city Holocaust monument located near to his house. “We are going nowhere. We will fight until our dying breath.”

With additional reporting by Valentine Strakovsky