The crimson thread of communism runs through the work of the great, lamented Australian historian, Stuart Macintyre.

He joined the Communist Party of Australia in the early 1970s as a New Leftist student of formidably theoretical tastes, and he transferred that membership to the Cambridge University branch of the British party when undertaking his doctoral studies.

His prize-winning doctoral thesis became his first book, A Proletarian Science (1980), an examination of the history of Marxism within the British working-class movement from 1917-1933. Macintyre’s second book, Little Moscows (1980), compared three of Great Britain’s mining and industrial towns, which had become genuine strongholds of communism. His first major project on return to Australia was a perceptive biography of a West Australian communist and union leader, Militant: The Life and Times of Paddy Troy (1984).

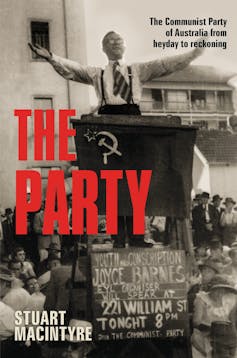

Review: The Party: The Communist Party of Australia from heyday to reckoning - Stuart Macintyre (Allen & Unwin)

Macintyre’s immense natural talents, prodigious commitment to his work, and restless curiosity led him to explore many other fields. He made important contributions to the historical study of liberalism, historiography, the universities, the social sciences, the Australian Labor Party, social justice, and much else besides.

He wrote an award-winning general history of Australia titled The Succeeding Age, 1901-1942 (1986), and a Concise History of Australia of such excellence that it ran to five editions. He served his profession and his community in countless voluntary and administrative posts, supervised scores of higher-degree theses, supported the careers of generations of Australian scholars, and helped to draft a new national curriculum in history.

Persistently, however, Macintyre came back to the topic of communism. In the early 1990s (originally with Andrew Wells), he embarked upon a research project on the history of the Communist Party of Australia. This resulted in The Reds: The Communist Party of Australia from origins to illegality (1998), an admired examination of the party’s origins up until the second world war.

In the years following The Reds, Macintyre turned to other projects, notably a fascinating and influential study of post-war reconstruction, Australia’s Boldest Experiment (2015). He notes with typically wry humour in his preface to The Party that he could not be accused of rushing to take on this second volume.

But as he also discloses in the opening pages of The Party, and as is now widely known, Macintyre was battling cancer as he worked on this new book. He continued to research and write as he endured repeated treatments, and had the pleasure of holding the completed work in his hands, weeks before he succumbed to illness in late November 2021.

For his many admirers, The Party will therefore be a bittersweet reading experience. We can be grateful that Macintyre was able to complete his labours, admiring of his energy and his commitment, but regretful that this is the last work of a gifted scholar who had so much more he wanted to give.

Read more: Vale Stuart Macintyre: a history warrior who worked for a better Australia

Distinctive individuals

In the opening pages of The Party, Macintyre outlines his purposes and defines the scope of his investigation. He will not offer a “comprehensive account” of Communist Party life from 1940 until dissolution. Rather, he will focus on the period in which communism was “most active and influential” in the 1940s and early 1950s, then go on to explain “the breakdown of old certainties” in the 1950s and 1960s.

These preoccupations are evident in the book’s structure. Macintyre devotes six chapters to the 1940s, four to the 1950s, and one to the 1960s; a brief epilogue projects the story forward.

The design liberates Macintyre to give full attention to the character and the distinctiveness of the Communist Party of Australia in what might be termed its “high-Stalinist” phase. He examines the operation of democratic centralism, the cultivation by party leaders of a monolithic unity, and the breadth of the party’s auxiliaries (or “fronts”) in the arts, peace, youth and women’s movements.

Along the way, Macintyre notes the exacting demands made upon party members, the arcane language, and the confidence of adherents that history was on their side.

These characteristics are richly illustrated with primary sources and strongly grounded in the close examination of individual lives. The Party is more a sensitive collective portrait than a dry institutional history. In Macintyre’s hands, party members are not a grey and uniform mass, but a collection of distinctive individuals.

There is Jack Blake, a Lithgow miner who studied Russian as well as Marxism: “tall”, “austere”, and a “formidable dialectician”. There is Patricia Thompson, who joined the Party via Sydney Girls High and a period of expatriation to London, and who was active in the Left Book Club and the Workers’ Art Guild.

Bruce Milliss was a Blue Mountains businessman and community dynamo, who held a secret party membership while running electoral campaigns for Labor luminary, Ben Chifley. Stan Moran, a graduate of the Lenin School in the Soviet Union, retained a native working-class larrikinism and was a weekly stump speaker in Sydney’s Domain.

Ted Hill, a “stocky, myopic man” with a “boyish face” and a “penetrating stare”, was a skilful tactician, yet characterised by such suspicious vigilance that he ordered the drawers be removed from all the desks in the party’s head office.

These rich portraits introduce the reader to a gallery of complex personalities: communists (if not communism) with a human face. In his examination of their rituals and connections, Macintyre provides an almost ethnographic understanding of the world of Australian communists.

Changing fortunes

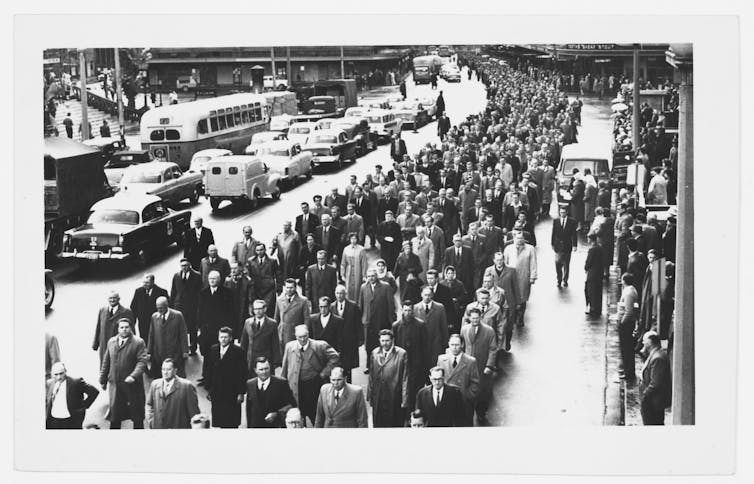

Macintyre’s skill in recapturing a lost political world is matched by a careful tracing of the Communist Party’s changing political fortunes. He narrates its rapid, almost miraculous rise, succeeded by a long and painful decline. The twists and turns of world politics play a significant role in these shifts. Soviet entry into World War Two largely initiates a boom time; the onset of the Cold War stalls and then reverses that growth.

Shifts within the communist world impose further pressures. Soviet leader Nikita Kruschev’s 1956 revelations about a “cult of personality” around Stalin precipitated an internal crisis and something of a reckoning in the Australian party. The Sino-Soviet dispute was eventually mirrored in a local party split.

Macintyre’s account bears the elements of a tragedy. And it is marked by a sad irony: as the party became more independent and open to difference, it also became more prone to factionalism and instability. A house divided could not stand.

Notwithstanding Macintyre’s past membership of the CPA and his reputation as a “Red Professor” (still publicised in the pages of Quadrant), The Party is a severe examination. The Communist Party’s Australian leadership is frequently exposed for its strategic missteps and its damaging illusions. The consequences of subservience to the USSR are fully explored.

The most sympathetic protagonists of The Party are communist union leaders like Jim Healy of the wharfies’ union: devotees of the interests of their working-class members, empowered by their political education within the party, but invigilated by functionaries who demanded adherence to often changeable and unreasonable dictates.

Party leaders rarely appear in such a positive light. Many of the notable contributions of communists to advancing social causes appear not so much due to their party membership as in spite of it.

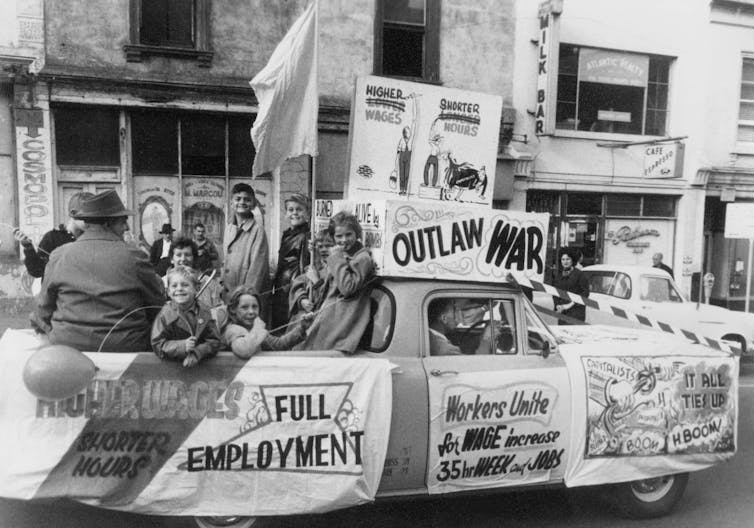

This clear-eyed examination of limits, failures and tensions is balanced by an exploration of the contributions of party members to the advancement of industrial rights and their involvement in campaigns supporting Aboriginal rights, colonial liberation and peace.

Macintyre also records the scale of the anti-communist mobilisation with which party members were forced to contend.

There were institutional campaigns through the Australian Labor Party’s Industrial Groups and B.A. Santamaria’s “Movement” of Roman Catholics. Royal Commissions were held into communism, and then espionage. Communists were excluded from civil organisations and prevented from holding meetings in town halls or on street corners.

There were prosecutions under the Crimes Act, media attacks, and everyday intimidation and violence. Communists were forced to contend with persistent surveillance by security services and they faced exclusion from employment for union activism or party membership, in some notable cases within the universities.

Illusions shattered

One of Macintyre’s achievements is to reconstruct the formidable reaction that Australian communism provoked. This not only helps to explain something of its failures and defeats, but also to reinstate the centrality of the battle over communism during much of the postwar era.

Read more: Australian politics explainer: the Labor Party split

Some readers will regret Macintyre’s decision to focus his investigation so rigorously on the 1940s and 1950s. Members of the Communist Party would continue to exert an influence on the Australian left and our society into the 1970s and beyond.

Jack Mundey of the Builders Labourers Federation of NSW was a party member when he helped to launch the “green bans” in the early 1970s; Laurie Carmichael of the Metal Workers Union was a party member when he helped to lead Australian unions towards a form of political unionism that would lead to an accord with the ALP.

The party lent its energies to many campaigns for social justice and equality throughout the 1970s and 1980s, It supported women’s liberation, East Timorese independence, and racial equality. Over these years, the party abandoned its quest for dominance and set out to pursue a “Coalition of the Left”.

Macintyre suggests that these initiatives represented a new development in the history of Australian communism. They therefore “require their own history”, something to be undertaken by another historian in another work.

But in setting out this history as he has – a history of illusions shattered, conclusions drawn, but still little practical action that registers these lessons – Macintyre conveys a strong sense of disappointment and of waste. Readers with left-wing sympathies will not find much to cling to in hope.

An eye for the emblematic detail

Like any book by Macintyre, The Party is based on a tireless immersion in the archives, a deep mastery of context, and a finely balanced literary grace. It is also enlivened by his enviable eye for the emblematic (and often amusing) detail.

To illustrate the wartime openness to communism, Macintyre draws attention to Newcastle races in 1942, a program that featured the “Stalin Flying Welter” and the “Molotov Improvers’ Handicap”.

To capture the zealotry of wartime security services and the censors, he recalls their seizure of the works of Shakespeare and their blue-pencilling of the Sermon on the Mount.

To symbolise the gravity of Communist Party defeat in the coal strike of 1949, Macintyre notes that the party was forced to sell off its Sydney headquarters “Marx House” to meet a shortfall in funds, and that the building was bought by the Coal Board “as a trophy of its victory”.

Macintyre’s observational skills make The Party a joy to read. His final observation is that “sooner or later” the overwhelming majority of communists left the party, but that this was “not before leaving their mark on this country”. Now Macintyre himself has left us. He has left behind a great contribution to Australian scholarship and self-understanding. The Party is a worthy and fitting final work.

Sean Scalmer has received funding from the Australian Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.