Steve Silberman, author of NeuroTribes, a groundbreaking history of autism that fundamentally changed how society understood autistic people, has died, aged 66.

While many people write about a community from the vantage point of an outsider, few can be credited with making the world a better place for that community. Silberman, whose death has left many of us truly devastated, was one of those few.

The science writer was also an expert on the Grateful Dead, the subject of his first (co-authored) book, and once worked as a teaching assistant for Allen Ginsberg.

“What connected his many interests was his affinity for underdogs and the misrepresented, whether it was the neurodivergent community, the gay community to which he proudly belonged, and, in a way, Deadheads,” Rolling Stone wrote in their eulogy.

‘A human community’

Silberman first became interested in autistic people when writing for Wired Magazine in 2001. “I came to it thinking I was going to study a disorder,” he told the Guardian. “But what I ended up finding was a civil-rights movement being born.”

His identity as a gay man influenced his approach to writing about autism as a “human community” rather than a “disorder”. He said: “My very being was defined as a form of mental illness in the diagnostic manual of disorders until 1974.”

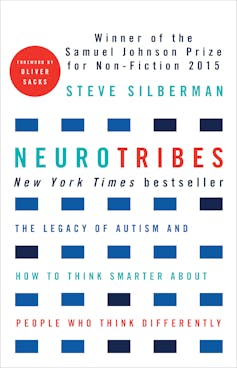

That interest ballooned into NeuroTribes (2015), a 534-page book called “ambitious, meticulous and largehearted” by the New York Times and “sparklingly humane” by the Guardian and was translated into 15 languages. In 2015, it became the first popular science book to win the prestigious Samuel Johnson Prize for Nonfiction.

‘He treated us as humans’

I have admired Silberman since I heard him interviewed about NeuroTribes on ABC Radio National’s Life Matters in 2016. From the beginning, he impressed me by quoting autistic people in his answers.

While discussing the eugenic propaganda of the early 20th century that portrayed disabled people as economic burdens, he made a statement I will never forget, which sadly remains just as relevant today. He pointed out that people still use this language, particularly in relation to the NDIS, then continued:

You still hear about autism as this tremendous economic burden on society, and why should able-bodied people make these sacrifices so that these people whose lives are less worth living, allegedly, can continue to exist. This is a horrible thing!

Silberman said he “always” flinched to see media stories about autism presented primarily in terms of their cost to society, for example “an estimated fifty million dollars a year”. He asked: “what is the cost of a human life? It’s inestimable and no one knows what someone’s potential is going to be, particularly when that someone is a child.”

Silberman had respect for autistic people. He did not treat us as inert material for a book upon which to build his reputation and career. He treated us as humans he could learn from. He understood the gravity of his position as translator between a minority community and the society that often dehumanises and excludes them.

Autistic journalist Eric M. Garcia, a columnist for MSNBC and author of We’re Not Broken: Changing the Autism Conversation, wrote that he was “devastated” and “gutted” by Silberman’s death. “He changed my life. Without his work, I never would have come around to accepting myself.”

A masterclass in writing about a community

NeuroTribes is a masterclass in how to write about a community when you are an outsider.

First, Silberman began spending time with autistic people early in his research process rather than doing it at the end, or not at all. He told autistic website Wrong Planet he was “very very glad” he had attended Autreat, a conference run by autistic people for them and their friends, early in his research process.

It revealed many “illusions” he’d had about autism: “implanted by simply reading hundreds of medical case studies and medicalized books about autism and fear-mongering articles about autism and seeing autism through the lens of tragedy, horror, and fear”.

He described benefiting from being around autistic people “enjoying themselves in an environment customized for their sensory needs that had a lot of space in it so that people could engage other people at whatever level they felt comfortable with, including not engaging at all”. He said it was “one of the most completely liberating environments that I had ever been in”.

Taking time to understand

Secondly, Silberman took the time to understand the history of autism, rather than assuming medical definitions were static. He was able to show that autistic people had existed long before the medical diagnosis of “autism” was coined in 1938 by Hans Asperger (who actually used the term “autistic psychopaths”) and in 1943 by Leo Kanner.

He also showed that since then, autism’s causes and criteria have frequently fluctuated to suit the agenda of the medical professional discussing it. For example, he wrote that child psychiatrist Leo Kanner changed his mind several times about whether parents were to blame for their child’s autism.

Silberman also highlighted how some researchers targeted both gay people and autistic people with damaging theories. For example, American clinical psychologist Ole Ivar Lovaas had a significant role in both the controversial autism treatment applied behaviour analysis (ABA) and the 1974 Feminine Boy Project, designed to treat homosexuality.

Both aimed to train a child out of “deviant” behaviours, such as flapping hands or limp wrists. The children would often be “trained” for hours at a time, surrounded by adults who would reward or punish every move the child made. The child was not allowed to eat, except for the tiny pieces of food that rewarded correct behaviour. Punishment included adults slapping them or screaming at them, blasts of sound at over 100 decibels, and electric shocks.

Finally, Silberman popularised the concept of neurodiversity, which was created by the autistic community throughout the late nineties. Australian autistic sociologist Judy Singer also wrote an honours thesis on it in 1998.

The catalyst for the idea was biodiversity – the idea that nature’s strength comes from many different species, which each have their place in an ecosystem. Similarly, autistic people proposed, humanity advances together when it draws on the strength of many varieties of minds.

Wrong about Asperger, but admitted it

NeuroTribes is not without its faults. It frequently praises Hans Asperger for protecting autistic children from being murdered during the Third Reich, but this was untrue.

Hans Asperger’s active role in the murders of autistic and other disabled children was proved by Herwig Czech and then Edith Sheffer in 2018. Once their work was public, Silberman admitted he knew of suspicions regarding Asperger in 2011.

It is difficult to understand why he ignored these suspicions about Asperger. There might not have been much evidence against Asperger at that time, but there was not much evidence in his favour either.

As Silberman points out, Asperger’s 1938 public speech on autism did suggest: “Not everything that steps out of the line, and is thus ‘abnormal,’ must necessarily be ‘inferior’”. However, in the same speech he also said “autistic originality can be nonsensical, eccentric, and useless”.

Asperger also said autistic people “don’t have personal relationships with anyone”. In an atmosphere where everyone was expected to work together for the benefit of the Third Reich, and where being anti-social was a crime, these words alone made autistic children candidates for euthanasia.

Importantly, though, when Silberman’s characterisation of Asperger was disproved, he did not deny or defend it, or accuse the autistic community of being ungrateful. He acknowledged his mistake – and continued on with his significant support for the autistic community.

“Steve Silberman was a writer for whom autistic people were never just a subject. We were his peers and his friends,” wrote autistic author Sara Kurchak. “Many autistic writers – including me – owe a great deal to his support.”

Amanda Tink does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.