The mood among South Africans has soured. The latest findings from the representative survey that’s done every year by the country’s Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) shows some disturbing new trends.

The most marked are:

a decline in levels of life satisfaction as a whole

a downturn in people’s views about what lies ahead in their lives

a growing sense of despondency, and

a declining satisfaction with democracy.

The sense of hopelessness and despondency with democracy that emerges from the survey does not bode well for the future of the country’s democracy. As the survey shows, as despondency increases, so too does a sense of hopelessness.

The 2021 survey – with the most recent available results – consisted of 2,996 South Africans aged 16 years and older living in private residences. The data were benchmarked and weighted to be representative of the adult population.

The survey echoes key points in our forthcoming work on life satisfaction and democracy in the Human Science Research Council’s flagship publication, State of the Nation. This details increasing life dissatisfaction amid growing unhappiness with democracy and despondency.

Read more: South Africans hold contradictory views about their democracy

Based on our two decade involvement in social attitudes research in South Africa, we argued that while South Africans were increasingly unhappy with democracy, their levels of life satisfaction remained stable. But we are now noting a significant decline in life satisfaction in the context of increased democratic despondency, weak political efficacy and mediocre service delivery.

It is this sense of hopelessness that could potentially signal political instability in the future.

What are people are saying

The Social Attitudes Survey is a nationally representative, cross-sectional survey. Conducted annually since 2003, it measures underlying public perceptions, values and social fabric in South African society.

The survey represents a notable tool for monitoring evolving social, economic and political values among South Africans. We also believe it shows promising use as a predictive mechanism that could inform decision makers and policy-making processes.

Read more: South Africa's 1994 'miracle': what's left?

The most recent survey results show a marked downturn in the mood in the country since 2021, most notably around life satisfaction and future life improvement or optimism.

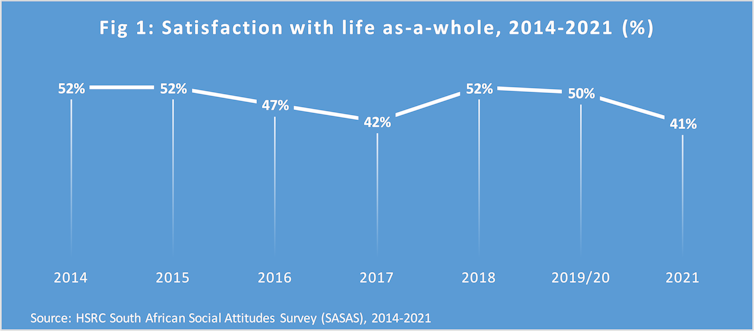

A downturn in life satisfaction: South Africans show a recent downturn in their general life satisfaction, a measure that has remained relatively stable over the last 18 or so years (Figure 1). When asked to reflect on their current personal life circumstances, only 41% were satisfied with their lives in late 2021 compared to 52% in 2014. This is a significant decline for a measure that is usually quite stable.

This points to appreciable strain on life satisfaction, something that is likely to be more acutely felt among poor and vulnerable citizens.

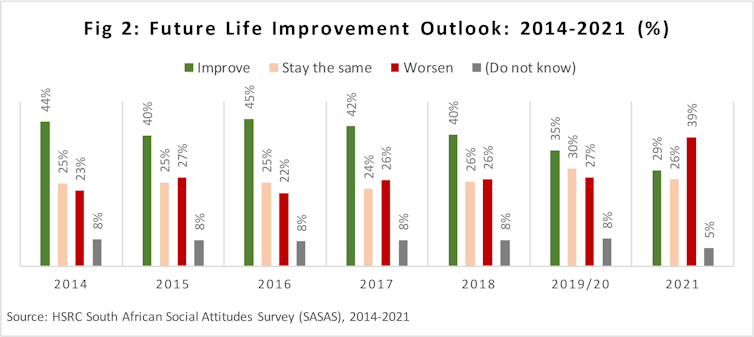

Outlook on future life: Trends in the outlook South Africans have for their future in the medium term also highlight despondency and hopelessness (Figure 2). In 2014, 44% felt their lives would improve over the next five years. In late 2021 this had fallen to 29%. The number who felt that life would worsen rose from 25% in 2014 to 39% in 2021. Those who believed that their situation would remain unchanged fluctuated between 22% and 30% over this period.

The 2021 results suggest that a threshold has been crossed, with a pessimistic outlook becoming more dominant than an optimistic one.

A sense of despondency: This was observed across all race and gender groups. But from a age profile perspective, older people held more negative views on future life optimism (Figure 3).

The drivers

Our analysis shows that personal future outlook of South Africans is strongly shaped by factors relating to the government performance evaluations, trust in institutions and general democratic evaluations.

Those with a more positive outlook were also more satisfied with government efforts at delivering a range of serives. These included the provision of water, sanitation and electricity, tackling crime and corruption, as well as job creation and social grants.

Those who thought these services were sliding had a more negative outlook.

Similarly, those expressing trust in national and local government, parliament, the Independent Electoral Commission, political parties and politicians all reported a sunnier outlook than those who were more sceptical.

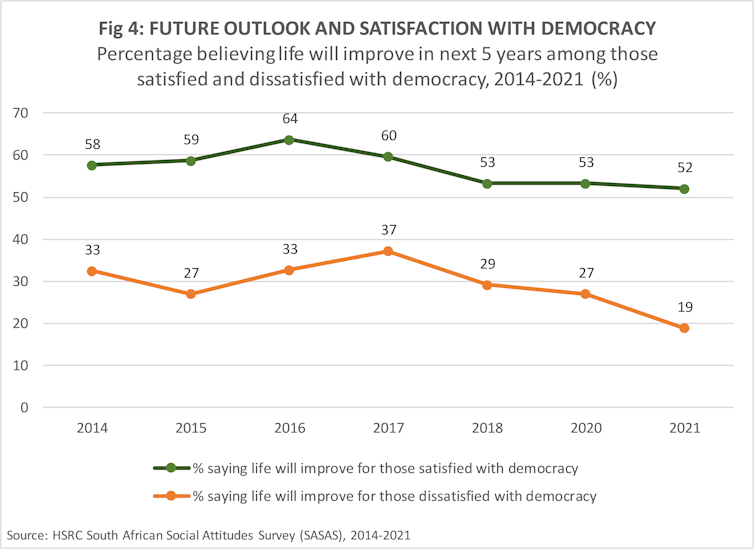

As an example of the scale of these effects, in Figure 4 below, we present the scale of difference in the share offering positive future expectations based on those that are satisfied and dissatisfied with democracy. On average over the 2014-2021 period, the difference between these two groups is 28 percentage points, rising to a high of 33 percentage points in 2021.

Democracy outlook

Up until 2020 there was evidence that South Africans, in common with other citizens across the subcontinent and Latin America, conventionally took a more optimistic view of the future through expressing that life would get better in the next five years.

However, as democratic despondency increases, so too does a sense of hopelessness in South Africans.

This begs the question of whether the Freedom Day 2023 mood should be a celebratory one, or one of sober reflection, and re-commitment to the social compact and spirit of accountability and government responsiveness that characterised the dream of 1994.

Joleen Steyn Kotze receives funding from National Research Foundation

Benjamin Roberts receives funding from various government and non-governmental agencies for commissioned content in each annual round of the South African Social Attitudes Survey (SASAS).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.