Israeli officials and Jewish South African activists inaugurated a memorial park in Tel Mond, a city north of Tel Aviv, in November 2022. Gan Siyabonga (We Thank You Garden) commemorates several dozen Jewish South African anti-apartheid activists who had personal connections to Israel.

The main sponsors of Gan Siyabonga are the Jewish National Fund South Africa and South African Zionist Federation. The park’s creation is a milestone in the South African Jewish community’s decades-long introspection into its complex relations with the apartheid regime.

This memorial site is unique in Israel, where an estimated 20,000 South Africans live.

Gan Siyabonga is the first site in Israel to highlight the involvement of Jews in the anti-apartheid struggle. It is also unique because it calls attention to a group that was both anti-apartheid and pro-Zionist, or at least not anti-Zionist. The combination is considered unconventional today. That’s because Zionism, the political ideology that favours a Jewish state, is largely associated in South Africa with collaboration with apartheid and the oppression of Palestinians.

Gan Siyabonga is a reminder that relations between Zionism and apartheid, and between Israel and South Africa, were complex and multilayered. In the last few years I have been working on a PhD dissertation that explores this complexity. Digging into archives and historical periodicals revealed a fascinating story that defies some assumptions.

Israel’s troubled relations with apartheid

Israel is commonly remembered as one of the last allies of apartheid South Africa. From the mid-1970s, the Israeli government maintained close relations with the minority white regime in Pretoria.

It was one of the last countries to enforce full sanctions on Pretoria. As a result, many anti-apartheid activists, including Jewish ones, held fierce anti-Zionist stances. These were amplified by the strong alliances South African liberation movements forged with the Soviet Union and the Palestinian Liberation Organisation.

Read more: Why the push led by South Africa to revoke Israel’s AU observer status is misguided

The accusation that Israel practises apartheid-like policies against Palestinians is another reason Israel hasn’t been seen as anti-apartheid. Recent anti-Zionist rhetoric by some Jewish veterans of the South African struggle, such as Ronnie Kasrils, strengthened this feeling of unbridgeable contradiction between Israel and anti-apartheid values.

Support for Israel

But anti-apartheid activism and Zionism were not always in conflict. Up until the late 1960s, many radical anti-apartheid activists were sympathetic towards Israel and Zionism’s more progressive strands.

In 1948, most radical activists in South Africa supported the establishment of the State of Israel and its war against the invading Arab armies in Palestine. The Guardian, the main radical weekly in South Africa at the time (linked to the South African Communist Party), rooted for an Israeli victory.

Young Israel was a symbol of opposition to racial persecution and fascism. Those two themes strongly resonated with South African anti-apartheid activists. They tended to see the Afrikaner National Party as an ideological relative of the Nazis.

The initial Soviet support for Israel, and a prominent socialist element within Zionism, also contributed to these feelings, especially among South African Marxists.

Read more: In search of advantages: Israel’s observer status in the African Union

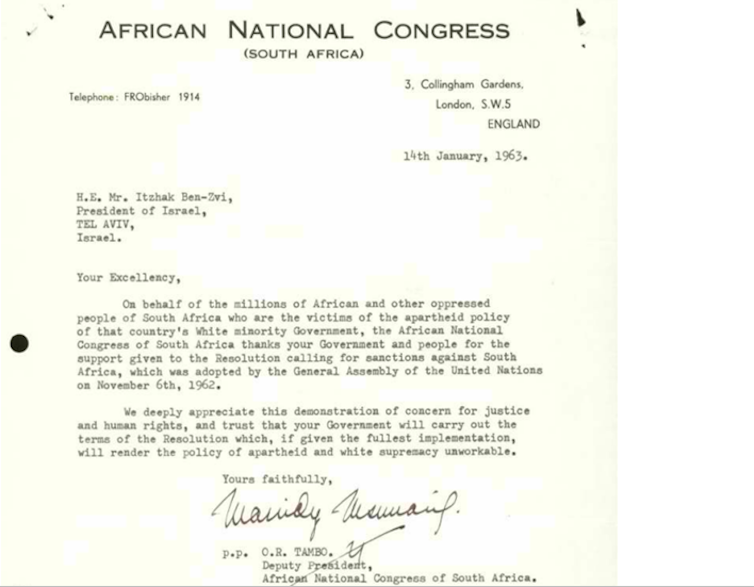

From the late 1950s, many anti-apartheid activists cherished Israel’s stances against South Africa at the United Nations. Similarly its support for decolonisation in Africa. By the early 1960s, Israel had become the most anti-apartheid country in the “western” camp of the Cold War. In 1963, it recalled its envoy and supported international sanctions against South Africa. Israeli archives contain many letters from South African liberation movements thanking Israel for its support at the UN and elsewhere.

During the 1960s, Israel offered covert material support to anti-apartheid groups, perhaps even to Nelson Mandela. Israeli experiences inspired the early stages of uMkhonto we Sizwe, the African National Congress’ (ANC) military wing, for example through Arthur Goldreich. It also had stable communication channels with the Pan-Africanist Congress of Azania.

Post-1967

Sympathy towards Israel diminished considerably after the Arab-Israeli wars of 1967 and 1973. But relations between anti-apartheid activism and Zionism remained complicated.

Many Jewish individuals who joined the struggle against apartheid had been active in Zionist youth movements. The socialist-oriented Habonim and Hashomer Hatzair stand out. Those who joined the anti-apartheid struggle (such as Joe Slovo and Baruch Hirson) typically abandoned Zionism. But they acknowledged its role in forming their radical worldview.

Jewish South African individuals were prominent in the liberal strand of the anti-apartheid struggle too. They usually used their professional skills to challenge the apartheid regime. Lawyers like Isie Maisels, parliamentarians like Helen Suzman, journalists like Benjamin Pogrund, and rabbis like Ben Isaacson were examples. Jewish liberal activists usually expressed support for Israel in various ways.

Developments since the mid-1970s have largely overshadowed the complex history of Zionism’s engagement with the apartheid regime. The anti-apartheid struggle became tightly associated with the Palestinian struggle. And, after its rise to power in 1994, the ANC reaffirmed its commitment to its Palestinian allies.

Read more: South Africa and Russia: President Cyril Ramaphosa's foreign policy explained

Since then, relations with Israel have largely remained chilly. The ANC supports the movement to boycott Israel and Pretoria downgraded its representation in the Jewish state. South African foreign affairs minister Naledi Pandor has called for Israel to be declared an “apartheid state”.

A step in the right direction

Israel and South Africa’s Jewish communities have a long and ambiguous history of entanglement with race politics. There were admirable moments in this history. But there were also periods of complicity with racism. In Israel, both sides of this history are largely forgotten.

Gan Siyabonga is an important first step in placing this history in the Israeli public sphere.

Asher Lubotzky does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.