People like beautiful things. This comes as no surprise: beauty underpins highly profitable businesses, from cosmetics and art to the illegal wildlife trade, which reaps up to US$23 billion (£20 billion) annually according to some estimates.

Tigers and pandas show that aesthetic value can be an asset to wildlife conservation, attracting public support and funding. On the flip side, anything that you might want to preserve in the wild so you can look at it, somebody else will probably want to own for the same reason.

The unsustainable trade in plants and animals can rapidly deplete wild populations and put species at risk of going extinct in certain areas, or even globally.

Songbirds (birds in the order Passeriformes) are an interesting case study. This group contains the greatest number of bird species, many of which are traded and many of which are threatened with extinction.

Canaries, for example, were originally sought as pets for the beautiful music they sing. But we need only look at their striking yellow feathers to see that colour – and beauty – also play a role in the popularity of songbirds.

Recent research I conducted with colleagues at the University of Florida in the US, the Centre for the Synthesis and Analysis of Biodiversity in France and Massey University in New Zealand, showed the colour of a songbird’s plumage predicts the likelihood of it being traded as a pet and its risk of extinction.

Colour by numbers

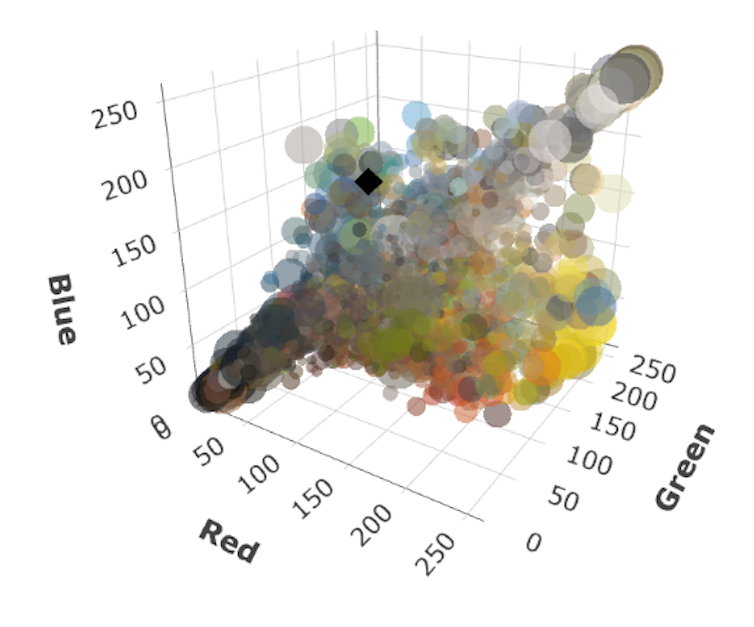

How do you quantify colour? We started off using data on the red, green and blue values of the colours that make up each species’ plumage. This is a standard way to quantify colour, which readers might be familiar with from television screens, for example.

Each primary colour of red, green and blue takes a value ranging from the minimum of zero to the maximum of 255. And these so-called RGB values together denote a specific colour. For example, a bird with 255 red, 204 green, and 255 blue would appear pale pink.

Unfortunately, you cannot easily identify and classify colours using these RGB values, so we converted them into colour categories using some simple maths. We used 15 categories, including the primary colours (red, green, blue), secondary colours (yellow, cyan, magenta), tertiary colours (orange, chartreuse green, spring green, azure, violet, rose), and the additional categories of brown, light (including white) and dark (including black).

Using a 3D graph with one axis for red, one for green and one for blue, we plotted every species according to the colour of its plumage. This allows you to see how rare the colours of different species are, based on how far away their colour is from others in the 3D space.

For the entire community of birds occurring in a given location, you can also look at how many colours are represented by those species based on how much of the 3D space they occupy. This we refer to as colour diversity.

Species at risk

Our results showed certain colour categories, such as azure and yellow, are more likely to be found on species that are traded than those that are not.

We believe that yellow is a common colour in the illegal wildlife trade partly because there are simply lots of species that are yellow. Azure, in contrast, is a colour found on far fewer species, but when it does occur it seems that it is highly likely to be on species that are heavily traded.

Other colours, such as brown, are less likely to be found on traded species compared with those that aren’t traded. Species with more unique colouration, such as pure white, have a generally higher probability of being traded.

What does this all mean for biodiversity? We identified nearly 500 additional species that are not currently traded but are at risk of being traded in future based on their colour and how closely related they are to currently traded species.

Since the tropics contain the greatest diversity of colours, in terms of both the range of colours exhibited by songbirds and the number of colourful species, this is where most colours would be lost if all currently traded species went extinct. The loss of these species would mute nature’s colour palette, leading to generally drabber bird communities with less colour variety globally.

This is just the first step in understanding the aesthetic value that underlies the trade in songbirds. A better understanding of what motivates this trade can help identify species that could benefit from monitoring and trade regulation.

Equally, identifying, celebrating and conserving hotspots of colour diversity has the best chance of conserving the aesthetic value of colour, as well as the overall biodiversity boasted by the tropics.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 10,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

Rebecca Senior does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.