Sloths are more vulnerable to the rising temperatures associated with climate change than other mammals, due to their unique physiology.

In a new study, my colleagues and I found that sloths’ ability to adapt to warming temperatures varies between the cooler, high-altitude and warmer, low-altitude forests of Costa Rica.

Unlike most mammals, sloths do not actively regulate their body temperature. Like reptiles, they rely heavily on ambient temperature to do so. This affects all aspects of their survival, including digestion, metabolism and movement. Combined with their extremely low-calorie, relatively inflexible leaf-based diet, these traits mean sloths have much less energy at their disposal than most other mammals.

As sloth body temperatures become hotter with rising temperatures, their metabolic rate increases. But those with sharply increasing metabolic rates are at risk of lower survival rates when temperatures rise, compared with other sloths.

Together with colleagues, including the founder of UK-based Sloth Conservation Foundation Rebecca Cliffe, I found that their degree of vulnerability depends on the altitude of the forests where each sloth originates from.

We calculated the metabolic rates of high- and low-altitude sloths across a range of temperatures using a method called respirometery. This involves putting a sloth in a large, closed box (comfortably) to measure how much oxygen it consumes at each temperature within an allotted time period.

Lowland sloths were able to slow their metabolic rate when temperatures became too hot. This is an important survival mechanism that may benefit these populations as climate change continues.

Highland sloths were unable to slow their metabolic rate, which increased with temperature and became critical above 32°C. Highland sloths are at another disadvantage – cooler, high-altitude forests tend to be smaller due to the slower growth rate of trees at higher elevations coupled with habitat loss. Highland sloths are therefore much less able to migrate and are more restricted than lowland sloths.

Sloths with higher metabolic rates use more energy, so they need to eat more food to produce more energy. However, due to their extremely slow rates of food intake and digestion, sloths take much longer to process food into energy than other mammals. Essentially, sloths cannot simply eat more food to match their energy requirements or achieve “energy balance” – the state where calories consumed equals calories burnt through physical activity.

Combined with inflexible migration options, the restricted metabolism of highland sloths makes them especially vulnerable to climate change. However, while lowland sloths appear to have more flexible metabolic responses to warming temperatures, they won’t be able to escape the effects of climate change if temperature increases are too extreme, putting their survival at risk as well.

There is a considerable lack of data on the current status and abundance of sloths. No comprehensive, long-term population monitoring has been conducted at a scale that reflects the true challenges sloths face.

Conserving cooler microclimates

My team of ecologists, who have been studying sloth behaviour and abundance across Costa Rica for 15 years, are concerned about how sloths are being affected by climate change. Areas once highly populated are now devoid of sloths, driven primarily by habitat loss and fragmentation resulting from extensive destruction of rainforests.

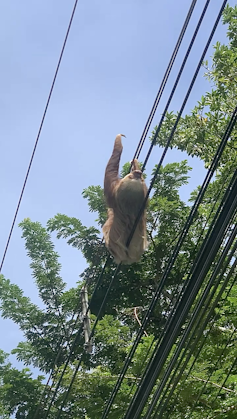

Costa Rica has transformed into a predominantly urban society over the past 40 years, with its urban footprint increasing by 112%. In the Talamanca province, where our team currently tracks wild sloths, urban sprawl has increased substantially with an estimated 3,000 sloths lost annually. Electrocution is one of the leading causes of admissions to wild animal sanctuaries in Costa Rica, partly because sloths use power lines to cross between fragmented forests in certain places.

Both native sloth species of Costa Rica are now listed as conservation concerns. Globally, an estimated 40% of all sloth species are threatened with extinction. Climate change poses a serious threat – and sloth conservation efforts need to take this into account. We predict that rising temperatures will have devastating consequences for sloths’ ability to maintain their energy balance and survive.

Sloth conservation is crucial, as they play a vital role in keeping the rainforest ecosystem healthy. Sloths are herbivores (plant eaters) that help regulate plant growth and recycle nutrients. They are an integral part of the food web, hosting a diverse ecosystem of unique organisms in their fur and serving as prey for other animals, such as ocelots and jaguars.

Protecting sloths is an incredibly complex challenge. Right now, natural habitats must be preserved and restored to support cooler microclimates. Particularly in vulnerable high-altitude regions, remaining forest fragments should be reconnected by building wildlife corridors – strips of natural habitat that connect fragmented areas and allow animals to move more easily.

Sloth conservation can only be achieved by addressing the root issue: climate change. A global, coordinated effort is required, with strict adherence to international climate accords such as the Paris agreement to limit global warming to below 1.5°C and prevent irreversible damage to rainforests.

If climate change continues unchecked, sloths won’t be able to migrate like other species. Once their environment becomes too hot, their survival is unlikely. Sloth conservation is directly linked to the actions humanity now takes to preserve our planet.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 35,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

Heather Ewart does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.