“Slavery is illegal everywhere.” So said The New York Times, repeated at the World Economic Forum, and used as a mantra of advocacy for more than 40 years. The truth of this statement has been taken for granted for decades. Yet our new research reveals that almost half of all countries in the world have yet to actually make it a crime to enslave another human being.

Legal ownership of people was indeed abolished in all countries over the course of the last two centuries. But in many countries it has not been criminalised. In almost half of the world’s countries, there is no criminal law penalising either slavery or the slave trade. In 94 countries, you cannot be prosecuted and punished in a criminal court for enslaving another human being.

Our findings displace one of the most basic assumptions made in the modern antislavery movement – that slavery is already illegal everywhere in the world. And they provide an opportunity to refocus global efforts to eradicate modern slavery by 2030, starting with fundamentals: getting states to completely outlaw slavery and other exploitative practices.

The findings emerge from our development of an anti-slavery database mapping domestic legislation against international treaty obligations of all 193 United Nations member states (virtually all countries in the world). The database considers the domestic legislation of each country, as well as the binding commitments they have made through international agreements to prohibit forms of human exploitation that fall under the umbrella term “modern slavery”. This includes forced labour, human trafficking, institutions and practices similar to slavery, servitude, the slave trade, and slavery itself.

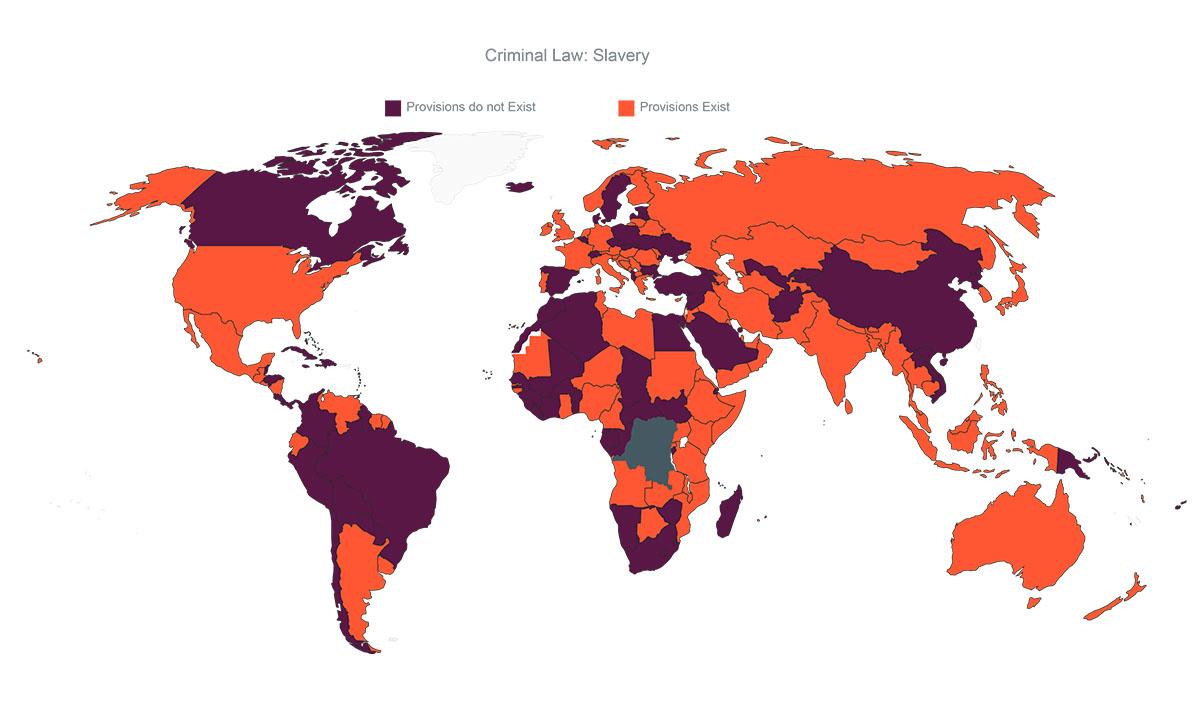

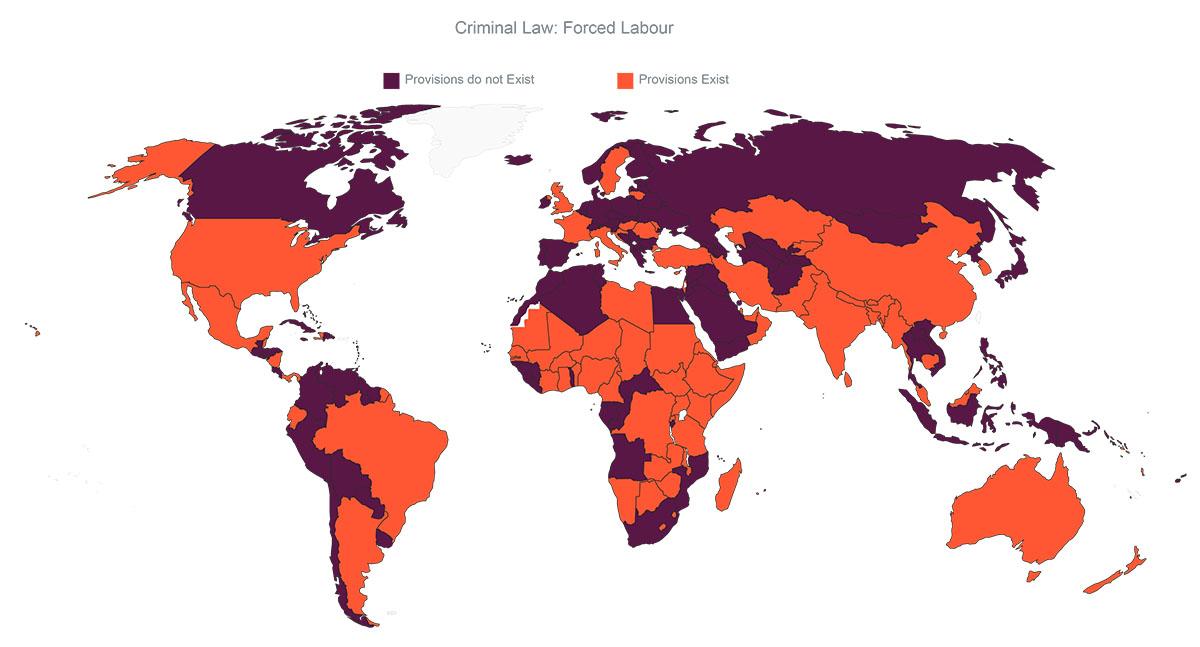

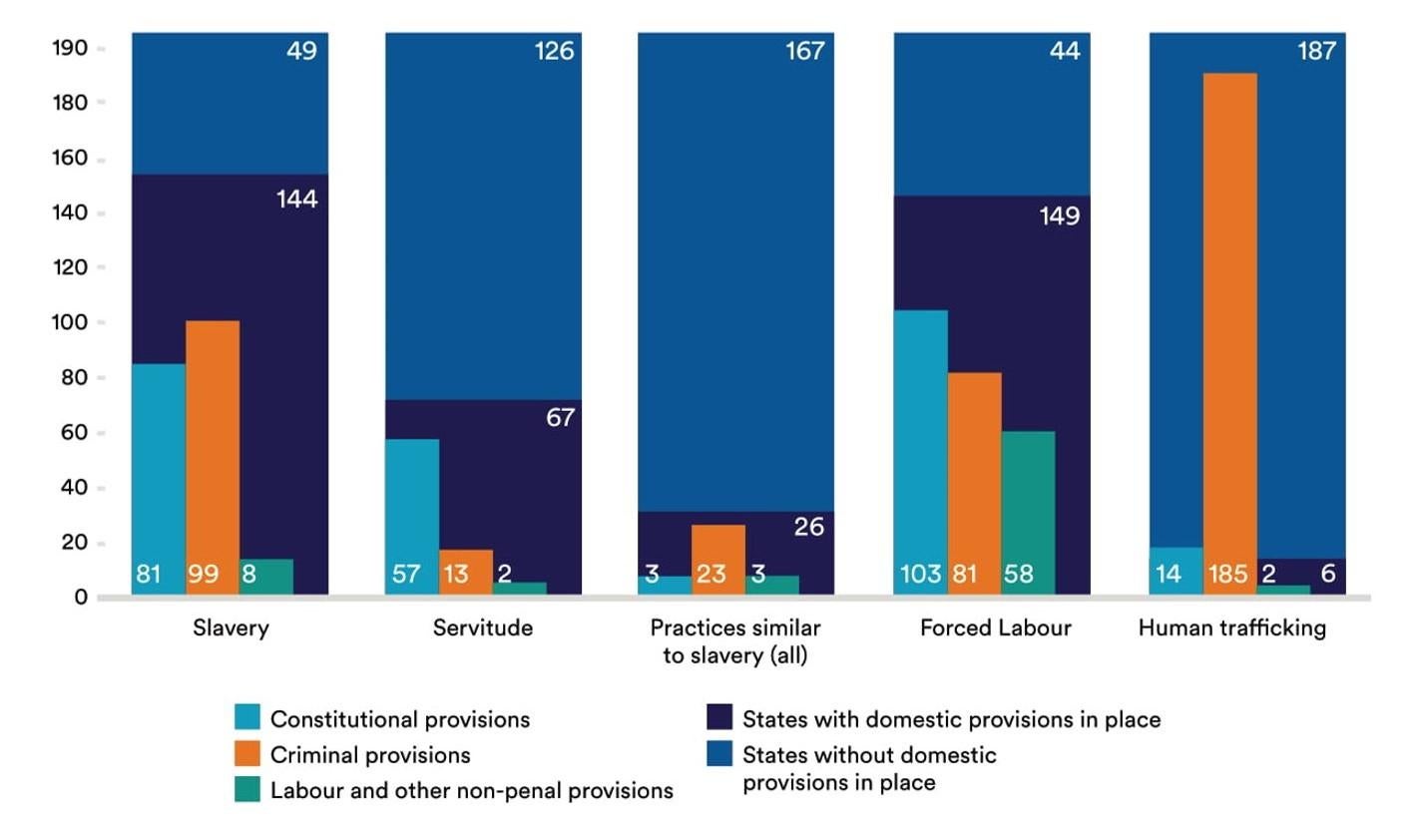

Although 96 per cent of all these countries have some form of domestic anti-trafficking legislation in place, many of them appear to have failed to prohibit other types of human exploitation in their domestic law. Most notably, our research reveals that:

- 94 states (49 per cent) appear not to have criminal legislation prohibiting slavery

- 112 states (58 per cent) appear not to have put in place penal provisions punishing forced labour

- 180 states (93 per cent) appear not to have enacted legislative provisions criminalising servitude

- 170 states (88 per cent) appear to have failed to criminalise the four institutions and practices similar to slavery.

In all these countries, there is no criminal law in place to punish people for subjecting people to these extreme forms of human exploitation. Abuses in these cases can only be prosecuted indirectly through other offences – such as human trafficking – if they are prosecuted at all. In short, slavery is far from being illegal everywhere

A short history

So how did this happen?

The answer lies at the heart of the great British abolition movement, which ended the transoceanic slave trades. This was a movement to abolish laws allowing the slave trade as legitimate commerce. During the 19th century, states were not asked to pass legislation to criminalise the slave trade, rather they were asked to repeal – that is, to abolish – any laws allowing for the slave trade.

This movement was followed up by the League of Nations in 1926 adopting the Slavery Convention, which required states do the same: abolish any legislation allowing for slavery. But the introduction of the international human rights regime changed this. From 1948 onwards, states were called upon to prohibit, rather than simply abolish, slavery.

As a result, states were required to do more than simply ensure they did not have any laws on the books allowing for slavery; they had to actively put in place laws seeking to stop a person from enslaving another. But many appear not to have criminalised slavery, as they had undertaken to do.

This is because for nearly 90 years (from 1926 to 2016), it was generally agreed that slavery, which was considered to require the ownership of another person, could no longer occur because states had repealed all laws allowing for property rights in persons. The effective consensus was that slavery had been legislated out of existence. So the thinking went: if slavery could no longer exist, there was no reason to pass laws to prohibit it.

This thinking was galvanised by the definition of slavery first set out in 1926. That definition states that slavery is the “status or condition of a person over whom any or all of the powers attaching to the right of ownership are exercised”. But courts the world over have recently come to recognise that this definition applies beyond situations where one person legally owns another person.

So let’s dig into the language of that definition. Traditionally, slavery was created through systems of legal ownership in people – chattel slavery, with law reinforcing and protecting the rights of some to hold others as property. The newly recognised “condition” of slavery, on the other hand, covers situations of de facto slavery (slavery in fact), where legal ownership is absent but a person exercises power over another akin to ownership – that is, they hold the person in a condition of slavery.

This creates the possibility of recognising slavery in a world where it has been abolished in law, but persists in fact. Torture, by analogy, was abolished in law during the 18th century, but persists despite being outlawed.

Stories of slavery

Slavery may have been abolished, but there are still many who are born into slavery or brought into it at a young age and therefore do not know or recall anything different. Efforts by non-governmental organisations to free entire villages from hereditary slavery in Mauritania demonstrate this acutely, with survivors initially having no notion of a different existence and having to be slowly introduced to processes towards liberation.

This is a country in which the practice of buying and selling slaves has continued since the 13th century, with those enslaved serving families as livestock herders, agricultural workers, and domestic servants for generations, with little to no freedom of movement. This continues despite the fact that slavery was abolished.

Selek’ha Mint Ahmed Lebeid and her mother were born into slavery in Mauritania. She wrote about her experiences in 2006: “I was taken from my mother when I was two years old by my master … he inherited us from his father … I was a slave with these people, like my mother, like my cousins. We suffered a lot.

“When I was very small I looked after the goats, and from the age of about seven I looked after the master’s children and did the household chores – cooking, collecting water, and washing clothes … when I was 10 years old I was given to a marabout [a holy man], who in turn gave me to his daughter as a marriage gift, to be her slave. I was never paid, but I had to do everything, and if I did not do things right I was beaten and insulted. My life was like this until I was about 20 years old. They kept watch over me and never let me go far from home. But I felt my situation was wrong. I saw how others lived.”

As this story shows, slavery turns on control. Control of a person of such an intensity as to negate a person’s agency, their personal liberty, or their freedom. Where slavery is concerned, this overarching control is typically established through violence: it effectively requires the will of a person to be broken. This control need not be exercised through courts of law, but may be exercised by enslavers operating outside legal frameworks. In the case of Mauritania, legal slavery has been abolished since 1981.

Once this control is established, other powers understood in the context of ownership come into play: to buy or sell a person, to use or manage them, or even to dispose of them. So slavery can exist without legal ownership if a person acts as if they owned the person enslaved. This – de facto slavery – continues to persist today on a large scale.

The stories of people around the world who have experienced extreme forms of exploitation testify to the continued existence of slavery. Listening to the voices of people who have been robbed of their agency and personal liberty, and controlled so as to be treated as if they are a thing that somebody owns, makes it clear that slavery persists.

In 1994, Mende Nazer was captured as a child following a militia raid on her village in Sudan. She was beaten and sexually abused, eventually sold into domestic slavery to a family in the Sudanese capital of Khartoum. As a young adult she was transferred to the family of a diplomat in the UK, eventually escaping in 2002.

“Some people say I was treated like an animal,” reflected Nazer, “But I tell them: no, I wasn't. Because an animal – like a cat or a dog – gets stroked, and love and affection. I had none of that.”

Human trafficking

Because of this remarkably late consensus on what slavery means in a post-abolition world, only very specific practices related to severe human exploitation are currently covered under national laws around the world – primarily, human trafficking. And while most countries have anti-trafficking legislation in place (our database shows that 93 per cent of states have criminal laws against trafficking in some form), human trafficking legislation does not prohibit multiple other forms of human exploitation, including slavery itself.

Human trafficking is defined in international law, while other catch-all terms, such as “modern slavery”, are not. In international law, human trafficking consists of three elements: the act (recruiting, transporting, transferring, harbouring, or receiving the person); the use of coercion to facilitate this act; and an intention to exploit that person. The crime of trafficking requires all three of its elements to be present. Prosecuting the exploitation itself – be it, for instance, forced labour or slavery – would require specific domestic legislation beyond provisions addressing trafficking.

So having domestic human trafficking legislation in place does not enable prosecution of forced labour, servitude or slavery as offences in domestic law. And while the vast majority of states have domestic criminal provisions prohibiting trafficking, most have not yet looked beyond this to legislate against the full range of exploitation practices they have committed to prohibit.

Shockingly, our research reveals that less than 5 per cent of the 175 states that have undertaken legally binding obligations to criminalise human trafficking have fully aligned their national law with the international definition of trafficking. This is because they have narrowly interpreted what constitutes human trafficking, creating only partial criminalisation of slavery. The scale of this failing is clear:

- a handful of states criminalise trafficking in children, but not in adults

- some states criminalise trafficking in women or children, specifically excluding victims who are men from protection

- 121 states have not recognised that trafficking in children should not require coercive means (as required by the Palermo protocol)

- 31 states do not criminalise all relevant acts associated with trafficking, and 86 do not capture the full range of coercive means

- several states have focused exclusively on suppressing trafficking for the purposes of sexual exploitation, and thereby failed to outlaw trafficking for the purposes of slavery, servitude, forced labour, institutions and practices similar to slavery, or organ harvesting.

Our database

While there is no shortage of recognition of de facto slavery in the decisions of international courts around the world, the degree to which this understanding is reflected in national laws has not – until now – been clear. The last systematic attempt to gather domestic laws on slavery was published over 50 years ago, in 1966.

Not only is this report now outdated; the definition of slavery it tested against – slavery under legal ownership – has been thoroughly displaced with the recognition in international law that a person can, in fact, be held in the condition of slavery. This means that there has never been a global review of antislavery laws in the sense of the fuller definition, nor has there ever been such a review of laws governing all of modern slavery in its various forms. It is this significant gap in modern slavery research and evidence that we set out to fill.

We compiled the national laws relating to slavery, trafficking, and related forms of exploitation of all 193 UN member states. From over 700 domestic statutes, more than 4,000 individual provisions were extracted and analysed to establish the extent to which each and every state has carried out its international commitments to prohibit these practices through domestic legislation.

This collection of legislation is not perfect. The difficulties of accessing legislation across all of the world’s countries make it inevitably incomplete. Language barriers, difficulties of translating legal provisions, and differences in the structures of national legal systems also presented obstacles. But these challenges were offset by conducting searches in multiple languages, triangulating sources, and the use of translation software where necessary.

The findings

The results, as we’ve shown, are shocking. In 94 countries, a person cannot be prosecuted for enslaving another human being. This implicates almost half of all the world’s countries in potential breaches of the international obligation to prohibit slavery.

What’s more, only 12 states appear to explicitly set out a national definition of slavery that reflects the international one. In most cases, this leaves it up to the courts to interpret the meaning of slavery (and to do so in line with international law). Some states use phrases such as “buying and selling human beings”, which leaves out many of the powers of ownership that might be exercised over a person in a case of contemporary slavery. This means that even in the countries where slavery has been prohibited in criminal law, only some situations of slavery have been made illegal.

Also surprising is the fact that states who have undertaken international obligations are not significantly more (or less) likely to have implemented domestic legislation addressing any of the kinds of exploitation considered in our study. States who have signed up to the relevant treaties, and those who have not, are almost equally likely to have domestic provisions criminalising the various forms of modern slavery. Signing onto treaties seems to have no impact on the likelihood that a state will take domestic action, at least in statistical terms. However, this does not mean that international commitments are not a significant factor in shaping particular states’ national antislavery efforts.

The picture is similarly bleak when it comes to other forms of exploitation. For example, 112 states appear to be without penal sanctions to address forced labour, a widespread practice ensnaring 25 million people.

In an effort to support their families, many of those forced into labour in developed countries are unaware they are not taking up legitimate work. Travelling to another country for what they believe to be decent work, often through informal contacts or employment agencies, they find themselves in a foreign country with no support mechanism and little or no knowledge of the language. Typically, their identity documents are taken by their traffickers, which limits their ability to escape and enables control through the threat of exposure to the authorities as “illegal” immigrants.

They are often forced to work for little or no pay and for long hours, in agriculture, factories, construction, restaurants, and through forced criminality, such as cannabis farming. Beaten and degraded, some are sold or gifted to others, and many are purposefully supplied with drugs and alcohol to create a dependency on their trafficker and reduce the risk of escape. Edward (not his real name) explains: “I felt very sick, hungry and tired all the time. I was sold, from person to person, bartered for right in front of my face. I heard one man say I wasn’t even worth £300. I felt worthless. Like rubbish on the floor. I wished I could die, that it could all be behind. I just wanted a painless death. I finally decided I would rather be killed trying to escape.”

Our database also reveals widespread gaps in the prohibition of other practices related to slavery. In short, despite the fact that most countries have undertaken legally binding obligations through international treaties, few have actually criminalised slavery, the slave trade, servitude, forced labour, or institutions and practices similar to slavery.

A better future

Clearly, this situation needs to change. States must work towards a future in which the claim that “slavery is illegal everywhere” becomes a reality.

Our database should make the design of future legislation easier. We can respond to the demands of different contexts by analysing how similar states have responded to shared challenges, and adapt these approaches as needed. We can assess the strengths and weaknesses of different choices in context, and respond to problems with the type of evidence-based analysis provided here.

To this end, we are currently developing model legislation and guidelines meant to assist states in adapting their domestic legal frameworks to meet their obligations to prohibit human exploitation in an effective manner. Now that we have identified widespread gaps in domestic laws, we must move to fill these with evidence-based, effective, and appropriate provisions.

While legislation is only a first step towards effectively eradicating slavery, it is fundamental to harnessing the power of the state against slavery. It is necessary to prevent impunity for violations of this most fundamental human right, and vital for victims obtaining support and redress. It also sends an important signal about human exploitation.

The time has come to move beyond the assumption that slavery is already illegal everywhere. Laws do not currently adequately and effectively address the phenomenon, and they must.

Katarina Schwarz is a Rights Lab associate director and assistant professor at the University of Nottingham, is a professor of international law at the University of Hull, and Rights Lab research fellow in survivor voices at the University of Nottingham. This article originally appeared in The Conversation