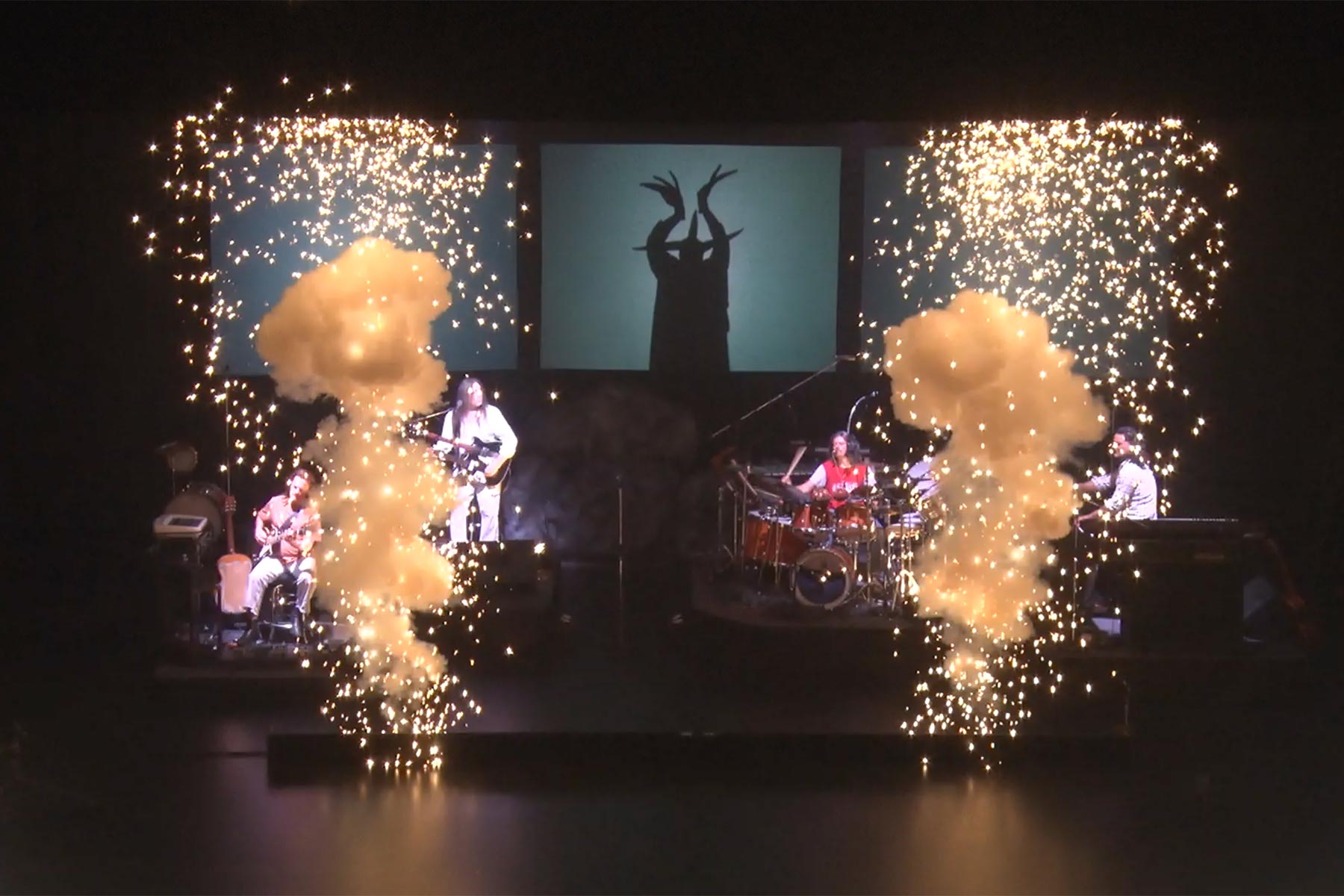

It starts with a frenetic piano solo, played hand over hand, two notes at a time, sounding like the first fast drops of a downpour soon to come. A panorama of Manhattan appears, parcelled out on three screens above the stage: the southern view of the island in the mid-1970s, smaller and lonelier than today’s cityscape. The light over New York shifts from dusk to night to dawn to day as the pianist plays nineteen bars, slowing down to make way for a single crash of cymbals. A picture of a curled-up and forlorn-looking baby sheep fades in across the skyscrapers on the middle screen, and a raspy voice sings the first line of the first song of the nearly-two-hour saga ahead: “And the lamb / lies down / on Broadway.”

I feel the hair on my skin spring to a stand. I enter an alternate life: it is 1975, and I am at a Genesis concert. The band is performing its new double LP, The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway, which tells the story of Rael, a young part–Puerto Rican graffiti artist who is pulled into a shadowy world full of peril, where he is seduced by a siren and turned into a pustular beast. Peter Gabriel, the band’s lead singer, plays both Rael and his grotesque “Slipperman” alter ego, leaping from a riser and darting across the stage in jeans and a leather jacket or lurching around in a bile-coloured, boil-covered leotard and giant round head. Behind him, guitar players Mike Rutherford and Steve Hackett, keyboardist Tony Banks, and drummer Phil Collins play intricate passages of which each note is inextricable from the story.

Yes, it’s bizarre: it’s progressive rock. The genre emerged in the late 1960s, mostly in England, and Genesis was a founding member. So were King Crimson, Pink Floyd, Yes, and Rush. Labyrinthine songs with unexpected shifts in key and metre, stories that feature ghosts and monsters and angels and aliens—these are the staples of prog, as it’s fondly known. You have to be highly skilled—virtuosic, even—to play it; to appreciate it, you have to be more than a bit nerdy. “Supper’s Ready,” the nearly-twenty-four-minute seven-part “song” that claims the entire second side of Genesis’s 1972 record Foxtrot, is perhaps peak prog, with what fans have speculated are references to theology, tautology, and pop culture. Gabriel frequently changed costumes during “Supper’s Ready,” at one point wearing a red headpiece made of two three-dimensional triangles as an incarnation of the menacing forces Gog and Magog, versions of which appear in the Old and New Testaments and also the Quran.

Gabriel walked away from Genesis in 1975, and Phil Collins took over as frontman. For a while, the band continued to play what I call Old Genesis songs—the material written and performed after Hackett and Collins joined, in 1970, and before Gabriel left. Collins sang them well but completely differently than Gabriel had. The costumes, the characters—all that was over, and seemingly forever. The band moved away from prog, at first perceptibly and then conclusively. By the mid-’80s, it was a pop band, keeping company on the charts with Madonna and Huey Lewis.

That’s when I fell in love with Old Genesis. I was in my mid-teens. It was a Sunday afternoon, and I was in the back seat of my parents’ station wagon, trying for the seventh or eighth time to read Rael’s impenetrable story inside The Lamb’s gatefold cover. Somewhere along the 401, I had an epiphany. I didn’t have to understand The Lamb. I could just accept it, absorb it, and enjoy it, in all its weirdness. Back at home, I played the record again, elated and despondent at once. Because I would never get to see my favourite band perform it live.

But then, miraculously, I did. In April 2022, wearing a face mask and a sweater that I had to take off repeatedly (hello, menopause), I saw an Old Genesis concert—word for word, note for note. Everything was as I’d imagined; everything was as it was—the lights, the sets, the costumes. Rutherford was even wearing the same white pants and shirt he always did. His long hair, as always, was hanging loose. But a trained eye would have caught this important difference: he was holding his guitar to the right, not the left.

In her book Send in the Clones, Georgina Gregory suggests that a number of systems converged in the mid-to-late 1970s to give rise to the first known tribute bands. One was the gaping grief that continued to simmer for years after the 1970 breakup of the Beatles; several of the earliest tribute bands paid homage to the Fab Four. Another was the birth of stadium rock, which meant fans would never again see groups like the Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin in anything like an intimate setting. And then there was the growth of a nostalgia culture around rock and roll. In its dawning days, rock music was defined by its shunning of the past; twenty years later, the hippies of the ’60s wanted to relive their youth.

The nostalgia around Old Genesis has a unique intensity. That incarnation of the band only really existed for about five years, and many fans missed its heyday. For us, the nostalgia is for something we didn’t experience; it’s almost nostalgia for nostalgia. Serge Morissette was thirteen when he became a Genesis fan. This was in 1973, the year the band released its fifth studio album, Selling England by the Pound. Morissette grew up near Thetford Mines, Quebec, a city of about 26,000, south of the provincial capital. He wasn’t old enough to travel to Quebec City for a Genesis concert until 1977, so he never saw them play with Gabriel. He came to understand the full extent of what he’d missed after moving to Montreal for university in 1979. He was part of a fan club that included people who had been to Old Genesis shows. They shared photos and talked about concerts they had been to, particularly one at the Université de Montréal’s sports centre, known as CEPSUM, in November 1973, when Genesis was touring Selling England. It changed their lives, they said. “What Peter was doing, it was totally credible,” one of them told Morissette. “You believed in the guy.” This fan showed Morissette some Super 8 footage he’d taped of a concert from the same tour as the CEPSUM show. After he saw the film, Morissette wanted to see the show. In person. More than ever.

I said Genesis fans are uniquely nostalgic, but Morissette doesn’t strike me as someone who has spent much time in “if only” land. He’s more of a doer. By 1993, he’d graduated from mechanical engineering at UdeM and was working at the Société de transport de Montréal. He had a side gig at the Spectrum, a beloved (and bygone) venue on Sainte-Catherine Street in Montreal, where he helped out with visual effects and video editing. The owners happened to be fans of Old Genesis. When Morissette proposed a show commemorating the twentieth anniversary of Genesis’s CEPSUM concert, they agreed.

And that was how Morissette met Sébastien Lemothe, a young Montreal bass player who had recently formed a band called the Musical Box (TMB). Unlike the handful of Genesis tribute bands gigging in the city’s club circuit, TMB played Old Genesis music exclusively, with a focus on songs from the Selling England tour. They had a real Mellotron, an analogue precursor to the modern sampler that went out of production in the 1980s, and were as intent on reproducing the exact sound of Selling England as Morissette was on making the show look exactly as it did in 1973: the same lights, the same sets, the same costumes. TMB was “a perfect fit” for his purposes, Morissette says, the only small wrinkles being that it was a seven-piece band (there had been only five musicians on stage at the CEPSUM show) and that the lead singer did not play the flute, as Gabriel had done on the tour. Morissette decided he could live with the discrepancies and invited TMB to be a part of his project.

The show was set to run for three nights. Tickets were $20 a piece, a price that seemed exorbitant for what people understood was a cover band. On the first night, “the venue was empty,” Morissette tells me. (In fact, he remembers, they sold around 200 tickets; the venue’s capacity was about 1,200.) But when the keyboardist played the ominous opening chords of “Watcher of the Skies,” and a caped figure appeared on a darkened stage wearing a batwing fascinator and UV paint around his eyes, the Genesis fan who had filmed the Super 8 footage of the original production stood beside Morissette and cried, “That’s it! That’s it!” A TV crew filmed a live spot, and it ran on the ten o’clock news; the next two nights sold out. TMB took the show to Quebec City, and it sold out there too.

Lemothe wanted to keep going, to keep tweaking the show and bring it as close as possible to the original performances. (Lemothe was not available to be interviewed for this story.) He hired Morissette as a kind of consultant. Soon, TMB was looking for a new singer; the original frontman left the band in 1994. Enter Denis Gagné, who also grew up in Thetford Mines. (Two other current band members grew up there—drummer Marc Laflamme and François Gagnon, the band’s “Steve Hackett.”) Gagné and Morissette had met years earlier at a lip-synched Genesis tribute show Morissette put on at the local CÉGEP. (Morissette tells me Gagné still has the poster from that show). Gagné auditioned and became the band’s “Peter.”

Gagné had a bar shaved down the middle of his scalp just like the one Gabriel had in the early ’70s. He watched hours of video so as to copy Gabriel’s movements, down to the way he held and hit his tambourine. He memorized Gabriel’s spiels between songs; when performing for French-speaking audiences, he spoke French (his first language) haltingly, just as Gabriel had done. He and Morissette studied photos of the glittery rainbow cape Gabriel wore in “Watcher of the Skies” and spent days trying to determine what it was made of. Was it transparent? How did it react to black lights? When they discovered that the particular fabric was no longer being made, they sought out old swathes from textile warehouses, managing to find it in only five of the seventeen colours included in the original cape. They had to stitch in other “close enough” material.

Over the next five years, TMB expanded its repertoire, adding reproductions of Genesis’s tours of Nursery Cryme, which came out in 1971, and more frequently of Foxtrot. By 1998, the band had built a big following in Quebec and seen some success in Ontario but struggled to find an audience anywhere else. TMB had formed a corporation, which was losing money. The band couldn’t keep paying to play, and they couldn’t play in Montreal and Quebec City forever. They decided to see if they could do the one tour they hadn’t yet tackled: The Lamb. If not, they would call it a day.

The first tribute band I ever saw was a group called Over the Garden Wall, a name taken from the Genesis song “I Know What I Like.” This was in the late ’80s, shortly after I’d moved to Montreal for university. The band played a mix of Old and post-Gabriel Genesis, and the singer wore parts of the costumes for some of the songs. I felt like I was at a party with sixty people who had also experienced a eureka moment in the back seat of their parents’ car. For the band, I felt a kind of awed gratitude. I could not quite fathom they were willing to play make-believe in front of a live audience.

I never sought them out again. I started following contemporary bands, and at some point, I became—like many people—dismissive of tributes. A prevailing notion took hold in the 1960s and ’70s that rock music should be original, authentic, written by the performer. Gregory points out that copyright laws have cemented this aesthetic, suggesting that “to perform anything other than one’s own material is symptomatic of creative bankruptcy.”

But the words “original” and “authentic” lie at the heart of TMB’s raison d’être. And to do The Lamb in proper TMB style, the band would have to recreate a slideshow that featured about 1,000 images, many of them staged: a gloved hand shaving a furry white heart with a straight razor, a man cradling a porcupine. The pictures accompanied the songs, but they were more than a complement—they were another layer of storytelling. There was no footage clear or comprehensive enough to discern each and every frame. TMB needed access to the original slides—but first, they needed permission to perform The Lamb at all.

Because it essentially qualifies as a musical (story plus music), anyone wanting to recreate The Lamb has to obtain a special licence called “grand rights.” Morissette reached out to Tony Smith, Genesis’s long-time manager, who said Morissette would have to ask Gabriel. He was eventually able to contact Annie Parsons, who worked at Gabriel’s record label, Real World. The answer was no, Parsons told Morissette: Gabriel wanted to adapt The Lamb himself. Morissette called her back. “Mrs. Parsons,” he said, “maybe my request isn’t clear. What we are asking for is permission to recreate The Lamb. Peter won’t recreate it; he will do something else with it. What we are asking for is not in competition in any way.” Morissette could hear the exasperation in Parsons’s voice, but she relented. “‘Send me some video, and I will ask him again,’” he remembers her saying.

About a month later, Morissette received a fax with Gabriel’s response: this time, the answer was yes. It took about two years in all to secure a one-year licence to perform the show. TMB paid to have the slides copied and delivered to Montreal. New costumes and sets were built over several months. Every single festering bubble on the Slipperman getup was reconstructed by hand, using clay and latex. TMB premiered its Lamb production on October 11, 2000, at the Spectrum and played several more shows in Quebec and Ontario over the next nine months.

The Lamb was a turning point. TMB had always seen itself as having less in common with a tribute band than, say, an orchestra playing Beethoven; now, Beethoven was taking the orchestra seriously. In 2002, when TMB brought its Selling England show on a seven-stop tour of the UK, the band members met Rutherford and Hackett at a rehearsal space in Chiddingfold, the Surrey village where Genesis’s recording studio, the Farm, is located. Hackett performed an encore with the band at Royal Albert Hall. Morissette visited Banks in his home. Gabriel saw TMB perform in Bristol and told Morissette to have Gagné phone him the next day. Gagné demurred; he was trying to protect his voice for the next show. “Serge looked at me and said, ‘Peter Gabriel is asking you to call him—you’re saying you’re not going to call him?’” Gagné tells me, speaking English with a slight British accent. He did, of course, speak to his archetype in the end.

In 2003, TMB visited the Farm, where they listened to the original Selling England tapes. They were also able to see the guitars Rutherford used on Genesis’s Selling England and The Lamb tours—both of them double-neck Rickenbackers, with a twelve-string guitar on one neck—which TMB had recreated for the left-handed Lemothe. That same year, after a second tour in Europe, TMB broke even for the first time. Since then, they’ve averaged about fifty shows annually, rotating between different productions. By the time I saw them play The Lamb in 2022, they were touring it for the fourth time. After the show, I did the math. Genesis put on just over 100 performances of The Lamb; TMB had played maybe three times that. I wondered if they knew The Lamb better than Genesis ever did. And also if they loved it better.

To see a TMB show as a fan of Old Genesis is to enter into a contract with the band. The band members will pretend to be Genesis and you will pretend to believe them. And in the course of the two-hour concert, if all goes to plan, there will be at least a few fractions of a second when you aren’t pretending.

At first, I thought this was why TMB mattered—because of people like me and Jack Beermann, who grew up in Skokie, Illinois. At sixteen, Beermann actually turned down the chance to go to a Lamb show in Chicago in 1975. “Ah, man,” he said to the friend who offered him a ticket. “I’m tired. My parents probably won’t let me go out. Thanks anyway.” After seeing Genesis play a year later—sans Gabriel—he went out and bought all the old records. “‘Supper’s Ready’ was the most amazing thing I’d ever heard,” he tells me. He became a super fan, collecting bootlegs, joining fan clubs, and going to see Genesis at least once on each of their subsequent tours. He heard about TMB through a Majordomo email list, and in 1994, he travelled to Montreal from Boston to see the band play at the Spectrum. As soon as the show started, he sat up in his seat. “I wasn’t expecting them to have a real Mellotron,” he says. When TMB performed “Supper’s Ready,” Beermann became emotional. Missing out on Old Genesis was “the biggest regret in my life,” he tells me. Seeing TMB, “I felt like I could rest.”

This is the kind of story I expected to hear. Then I talked to Thomas Manchon, who was born in 1987 and went to see TMB’s Selling England show in Paris in the early 2000s. He didn’t know anything about the costumes or the theatrics. “It was totally new for me,” he says. “It was just like a teenager in the ’70s going to a Genesis show.” It takes me a moment to grasp what this means: in a sense, for Manchon, TMB is Old Genesis. He never had to mourn what he missed: he never missed anything. “The first time I heard ‘Supper’s Ready’ was during a Musical Box show,” he says.

For the past several years, Manchon has been helping TMB find Old Genesis archival material. In 2021, he sent Morissette some footage from a 1974 Selling England concert in Santa Monica. In the middle of the song “Battle of Epping Forest,” Gabriel took off his hat and threw it on the floor behind Rutherford. Morissette called Gagné and Lemothe immediately; none of them had ever seen Gabriel do this before. “We were yelling like kids,” says Morissette. This hat throw will likely show up in TMB’s refreshed Selling England show, on a tour that begins in November. It will be fifty years since Genesis played at the CEPSUM.

Morissette likens what TMB does to archaeology. I keep wondering whether it can be called art. Ian Benhamou, who joined TMB as keyboardist in 2018, thinks the word “artistic” might apply better; after all, he says, TMB is not creating anything new. But when I ask the band’s drummer, Marc Laflamme, “Is it art?” he is categorical: “It definitely is.” With TMB’s commitment to detail and accuracy, he says, they have invented a new way of paying tribute to Genesis. It’s not that they’re necessarily better than other Genesis tribute bands. It’s that they are the most devoted.

I ask Morissette who or what all his painstaking replication work is for. Is it for Genesis fans? Is it for Genesis? Is it in the name of some larger cause: the preservation of art? “Oh, it’s for me,” he says. He tells me that he started recreating the shows because he never got to see the real ones. But then it dawned on him that when he’s watching live music, he lives in the present. “It means I’m happy,” he says. “I’m living in the moment that is happening. I’m not thinking about the future or the past.”

I ask if he ever has a moment, like I did in The Lamb show, when he feels as though he’s watching the original band. He says that he is especially satisfied when TMB plays “Apocalypse in 9/8”—the sixth section of “Supper’s Ready,” when Gagné comes out wearing the geometrical headgear, and behind him, a special projector throws flames onto the sets. “For me,” he says, “it’s Genesis.” Does he enter an alternate reality? Does he forget that both he and the band are pretending? I doubt it. But I like to think that, at some point, the fact that Rutherford is holding his double-neck guitar to the right rather than the left blurs into the background. Just for a few fractions of a second.