Scientists have uncovered antibodies that target the "dark side" of the flu virus.

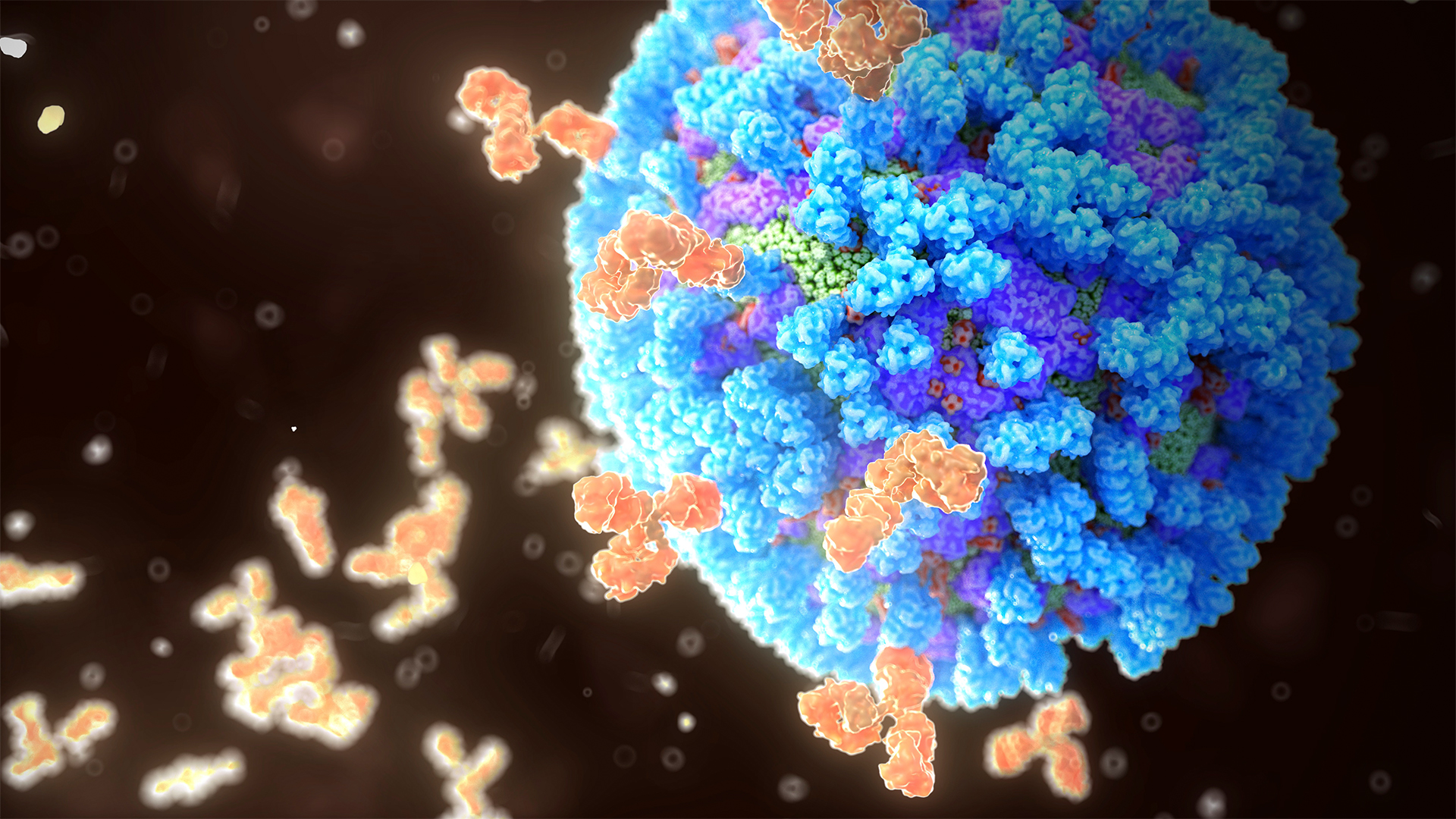

Influenza viruses have a mushroom-shaped protein known as neuraminidase (NA) that is said to have a "dark side" because the structure beneath its mushroom cap has been largely unexplored by science. Antibodies that latch onto this dark side could help form the basis for antiviral drugs and vaccines that work against many flu viruses, researchers wrote in a paper published Friday (March 1) in the journal Immunity.

Currently, flu vaccines are designed to target a different structure on the surface of flu viruses: hemagglutinin (HA). This lollipop-shaped protein lets the viruses latch onto the outside of human cells and then infiltrate them. But it mutates rapidly, which is why the flu shot must be updated every year to match the HAs of circulating flu strains.

Related: Never-before-seen antibodies can target many flu viruses

By comparison, the dark side of NA doesn't mutate nearly as fast and it looks very similar in different strains of flu virus, according to a statement from the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

NA is thought to help flu viruses navigate to their preferred receptor on the outside of host cells. Then, once a virus has infected a cell and multiplied inside it, NA helps those new viruses exit the cell. Several antiviral drugs for the flu, including Tamiflu (generic name oseltamivir), actually work by inhibiting NA and thus preventing flu viruses from escaping cells they've infected. Mutations that tweak the structure of NA can therefore make viruses less vulnerable, or resistant to such drugs.

Scientists have only ever discovered a handful of human antibodies against NA, and these generally latch onto the top or the side of the protein's mushroom cap, the researchers noted in their report. These parts of the mushroom are more prone to mutating in ways that help flu viruses dodge the effects of antiviral drugs, they added.

In their new study, the NIH scientists analyzed blood drawn from two people who'd been infected with H3N2, a subtype of influenza A virus that spreads seasonally and mutates especially quickly. In the blood samples, the team identified six antibodies that latch onto the dark side of NA.

In laboratory tests, these antibodies latched onto a number of different H3N2 viruses and slowed their replication. The antibodies also worked against a different type of influenza A, called H2N2.

In experiments with mice, the antibodies saved many rodents from a lethal dose of H3N2 virus, which hints they could be useful for the prevention and treatment of influenza in people. The antibodies showed strong protection both when they were given to mice prior to infection and when they were given afterward. The team also tested how the antibodies fared against some drug-resistant strains of flu and found they still showed the same degree of protection.

To better understand how these antibodies work, the researchers used cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM), a microscopy technique that uses beams of electrons to reveal the detailed 3D structures of molecules. The team used this to zoom in on two of the antibodies as they grabbed hold of NA. The experiment showed that the two antibodies target different parts of the dark side that don't overlap.

This suggests multiple features of the dark side could be targeted with future medicines or vaccines, and it opens up the possibility to take aim at multiple regions at once, for instance.

"Our findings help guide the development of effective countermeasures against ever-changing influenza viruses by identifying hidden conserved sites of vulnerability on the NA underside," the study authors wrote.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!