You don’t have to be a comedian to know that to explain a joke is to ruin a joke. Yet satirical US news site The Onion is doing just that, albeit reluctantly, in an effort to protect the right to tell those jokes without fear of arrest.

The self-declared “world’s leading news publication” filed an amicus brief to the Supreme Court this week in support of a man who was arrested and prosecuted for creating a parody Facebook page of his local police department. Anthony Novak’s civil rights lawsuit was dismissed by a district court in April of this year, which led him to ask the Supreme Court to intervene, citing a breach of his violation of First and Fourth Amendment rights.

The case could provide an important test, in the country that gave the world Mark Twain, of the right of satirists to mimic their subjects without falling foul of the law.

The Onion, known for its sardonic and irreverent headlines (“Children, Creepy Middle-Aged Weirdos Swept Up In Harry Potter Craze”) and its use of humour to address serious issues such as mass shootings (“‘No Way to Prevent This’, Says Only Nation Where This Regularly Happens”), filed a 23-page brief in support of Mr Novak on Monday.

The brief is a spirited defence of parody as protected under the First Amendment. It is also, in parts, a work of parody itself.

“As the globe’s premier parodists, The Onion’s writers also have a self-serving interest in preventing political authorities from imprisoning humorists. This brief is submitted in the interest of at least mitigating their future punishment,” it reads.

It further notes that “the federal judiciary is staffed entirely by total Latin dorks: They quote Catullus in the original Latin in chambers. They sweetly whisper ‘stare decisis’ into their spouses’ ears,” before declaring its own writers “far more talented” than the “hack” Jonathan Swift.

The brief is a departure from the staid language of a typical amicus brief, but that is precisely the point, according to its primary author, Mike Gillis, head writer at The Onion.

“I hope it’s taken in the spirit that it’s intended, which is a sincere defence of parody, and why parody deserves this kind of historic space to operate, and why that should be kind of a blanket protection for all US citizens,” he toldThe Independent by phone this week.

The Onion was founded in Wisconsin in 1988 as a small campus newspaper and grew to a valuation of $500m in 2016. It became aware of the case through a mutual friend of the publication’s managing editor who was involved with the case.

“Our legal team looked at it, our editorial team looked at it, and we decided that it was not only interesting on its own merits, but it was also symbolic of the kind of protection that we want to see parody law afforded in the US, and has historically been afforded in the US,” Mr Gillis says.

He wrote most of the brief in one go, with input from The Onion’s own legal team and Mr Novak’s.

The brief is centered around the case of Mr Novak, a resident of Parma, Ohio. In March 2016, Mr Novak created a Facebook page that parodied the Parma police department’s online page. After receiving nearly a dozen calls from members of the public who didn’t get the joke, Parma police arrested Mr Novak, seized his electronics and charged him with a felony law that criminalises using a computer to disrupt police operations. Mr Novak was prosecuted, but found not guilty at trial.

The case might have ended there, but when he filed a civil rights case over his arrest it was thrown out by the Sixth Circuit. The court’s reasoning was that police “could reasonably believe that some of Novak’s Facebook activity was not parody”, in part because Mr Novak “delet[ed] comments that made clear the page was fake”.

The Onion, which for years has fooled politicians and other news outlets into mistaking its own satirical articles for genuine news, saw a hole in the court’s argument. It argues that the court’s requirement that Mr Novak identify his work as a parody negates its very purpose.

“I think the Sixth Circuit ruling seemed to misunderstand what parody is,” says Mr Gillis. “It is mimicking a thing. It’s trying to deceive the reader at first. Not entirely, but to give them a sense of being led down one path with a setup, and then hit with a punchline.”

As the brief notes: “The point is instead that without the capacity to fool someone, parody is functionally useless, deprived of the tools inscribed in its very etymology that allow it, again and again, to perform this rhetorically powerful sleight-of-hand: It adopts a particular form in order to critique it from within.”

“Put simply, for parody to work, it has to plausibly mimic the original,” it continues.

To demonstrate this point, The Onion’s amicus brief “pulls back the veil”, as Mr Gillis describes it, on how its own writers mimic the news outlets and leaders it parodies. The first chapter of the argument includes a lengthy example of a story The Onion might write: “Supreme Court Rules Supreme Court Rules,” and explains the reasons why it mimics the strict style of the Associated Press.

“That rhetorical form sets up the reader’s expectations for how the idiom will play out – expectations that are jarringly juxtaposed with the content of the article,” it says.

The brief continues not just as a defence of the method of parody, but its purpose and power. Parodists, The Onion argues, “can take apart an authoritarian’s cult of personality, point out the rhetorical tricks that politicians use to mislead their constituents, and even undercut a government institution’s real-world attempts at propaganda”.

It points to numerous examples of Onion articles being mistaken for the real thing by the very people it was mocking. It notes that a 2012 Onion article declaring Kim Yong-un as the sexiest man alive, for example, was picked up by the Chinese state-run news agency, together with a slideshow. Republican congressman John Fleming sounded the alarm for his constituents when he was taken in by an Onion story with the headline: “Planned Parenthood Opens $8 Billion Abortionplex.”

“The point of all this is not that it is funny when deluded figures of authority mistake satire for the actual news – even though that can be extremely funny,” the brief reads. “Rather, it’s that the parody allows these figures to puncture their own sense of self-importance by falling for what any reasonable person would recognise as an absurd escalation of their own views.”

Mr Gillis contends that the protections for parody rest on the idea of a “reasonable reader”. This is to say: a parody doesn’t have to be understood by everyone for it to be protected, only by a reasonable person.

“I mentioned this in the brief, the idea that Kim Jong-un legitimately believed that he was the sexiest man alive in the early oughts – that shows that he’s not a reasonable person. But the average reader is absolutely able to see that’s ridiculous,” he says.

Mr Gillis continues, saying that the “number of people who have fallen for our jokes is pretty daunting, but it weighs very heavily towards the deluded, the deeply confused, propagandists and authoritarians”.

“I think that’s because they are living in this elevated world that they’ve created for themselves,” he adds. “And so when we produce a piece of satire, it feeds into that kind of rarefied air that they exist in. I think the Sixth Circuit really underestimates the reader because what we’re doing wouldn’t be very funny at all if people couldn’t see through it at some point.”

The Onion’s intervention is a rare one, Mr Gillis says, and one that was made reluctantly.

“I don’t think anybody wants to see a comedian put themselves on high and dissect point by point why what they’re doing is extremely important on a day-to-day basis. I think once in a while it’s extremely interesting because it’s something that’s very rarely discussed,” he adds.

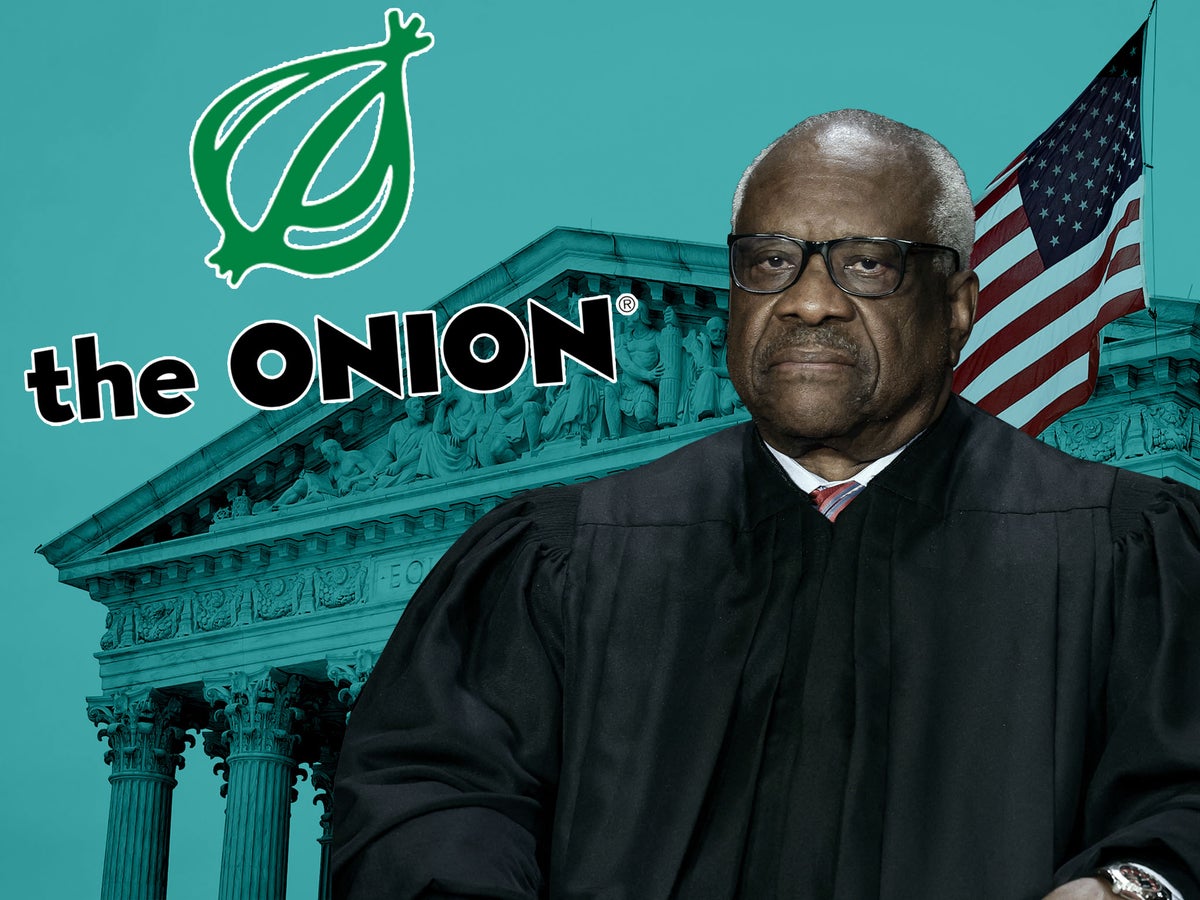

The question is: will Supreme Court judges get the joke? It is an institution not well known for its sense of humour, after all.

“Au contraire,” Mr Gillis responds. “I think Clarence Thomas told a joke back in 2013 and by all accounts it was hilarious.”