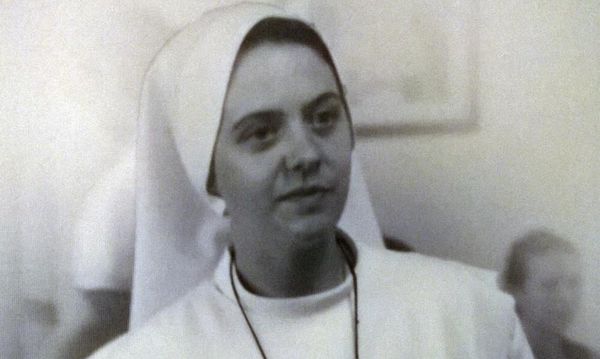

Sarah Finch considers herself an early adopter of environmentalism, even if she is not quite sure what the initial spark was. “I was only ever interested in the environment,” she says. “That’s all I wanted to do.”

She never expected her name to become part of legal history. Last week, the supreme court handed down a landmark ruling in a lawsuit that Finch fronted, ruling that the climate impact of burning coal, oil and gas must be taken into account when deciding whether to approve projects. It set an important legal precedent and threw doubt on the approval of new fossil fuel projects in the UK.

The seeds of Finch’s campaigning were sown in the 1980s, when her first job was in the Campaign for Lead Free Air, helping to overcome public suspicion of lead-free motor fuels. “That was a great experience,” she says. “We used to have quarterly meetings with the departments of transport, health and environment, representatives of the oil companies, representatives of the motor manufacturers. I got to see how decisions are made.”

At the turn of the millennium she spent six months as a press officer at the Jubilee 2000 debt cancellation campaign. “That was massive. It felt like we had rock stars, we had the world. And then when that ended we were talking about what we were going to do, and I thought: ‘I want to do that for the climate.’”

The supreme court decision last week was the culmination of years of work by Finch and a dedicated group of local campaigners fighting oil extraction in the Weald in Surrey.

Finch first became concerned when she saw a notice in her local paper in 2010 about plans by a developer to drill for oil at Horse Hill. But it was not until high-profile anti-fracking protests 10 miles away in Balcombe that she and others decided to take their campaigning up a notch.

“I was very involved in the Balcombe campaign and it made me look back at the Horse Hill application and see that it was basically a copy and paste job. So I thought, OK, Horse Hill is going to be another Balcombe.”

But the dynamics were different: Balcombe was a tight-knit village with a strong community, whereas the proposed Horse Hill site was remote. Finch acted as a bridge between more traditional local campaigners and anti-fracking activists coming in from elsewhere, and eventually helped set up a wider network called the Weald Action Group. It held community meetings, liaised with the council over protester arrests and opposed some of the many exploratory applications going through at the time.

In 2018, UK Oil & Gas put in a planning application for four new oil wells and full-scale production for 20 years. “That was a massive escalation,” says Finch. With the public attention now off fracking, campaigners turned to the huge climate impacts of these kinds of developments.

Initially, they sought a judicial review of the decision to grant Horse Hill planning permission, arguing that greenhouse gas emissions from burning the extracted oil had not been considered and it was therefore illegal.

“But it very quickly became obvious that it was wider than that,” says Finch. “One reason was that the government attached themselves very early on as an interested party. And then Friends of the Earth intervened on my side. There was a principle at stake.”

Finch never intended to be the figurehead of the legal cases. But no one else was keen to step in and, given assurances that it would probably be over in six months, she agreed to take it on.

Lawsuits are expensive and the first two rounds of the case only went ahead thanks to a huge amount of fundraising. There were gigs, an art sale and an auction. One 71-year-old woman raised thousands of pounds doing a 100-mile sponsored walk between various oil sites.

Having lost at the court of appeal, Finch and her fellow campaigners were uncertain whether to continue. But the organisation Law for Change stepped in at the last minute to cover the costs and they were encouraged to take the final step.

With the supreme court finally having ruled in her favour, Finch says she feels “absolutely vindicated but also a little bit angry, because it’s taken five years and haven’t we said the same thing all along?”

Finch is wary of painting the case as a David and Goliath battle, noting its success was down to the hard work of many people. “It just happens to be my name that’s written on the front sheet. The group has a range of strengths and they don’t let you stop. So there’s been times I’ve thought, I want to take a break from all this, and then I’ll ring up and they say: ‘You’ve got it.’

“But I also feel hugely privileged, because I know plenty of other people who’ve spoken truth to power and it hasn’t gone the right way.”

Despite the ruling, Finch is not optimistic about the way things are going. “I hope the judgment is a tipping point and will make it much harder for any new oil and gas sector to be exploited both in the UK and in other countries with similar legislation. But there’s already more than enough oil and gas and coal in production to wreck the climate, even if we stopped all new production today, so I just don’t see us weaning ourselves off it fast enough.

“But every tonne of carbon released makes things a tiny bit worse so I think you just have to do what you can do. I feel it helps my climate anxiety to be doing something even if I think it’s futile in the face of the challenges.”