The Russian who now goes by the name of Janosh Neumann had a clear plan for how things would unfold once he crossed the threshold of the US embassy on the Caribbean island he chose as his hideout.

Neumann would offer the CIA chapter and verse about his years as a Russian intelligence officer and his work after that as a bag man for a Moscow bank specialising in money laundering. He would lay bare the intricate web of ties between Russia’s security service, the FSB, organised crime and Moscow banks. He would name names.

Neumann also knew he would have to frankly admit he too was on the take, accepting bribes and his cut of illegal deals.

In return, the Russian wanted the CIA to provide a foreign passport to somewhere quiet, he had in mind Denmark or Switzerland, and a fat chunk of money: something in the region of the $2.5m he calculated he made from money laundering over the previous three years, most of which was spent or left behind when he fled Moscow. Neumann, who was born in the then Soviet Union 36 years ago and came of age during its collapse, needed a new paymaster and a new life with his wife, a former FSB agent now called Victorya.

That was the plan, and for a while – as the CIA smuggled Janosh and Victorya through the Caribbean by yacht, and the FBI installed the couple in a luxury hotel for months and showered them with cash – it looked as if it might work out.

But seven years and several identities later, the Neumanns find themselves trapped in a nightmare after what he describes as a virtual abduction to the one place they did not want to go: the United States.

The relationship with the CIA, and later the FBI, unravelled amid accusations on both sides of betrayed promises and lies. That has left the Russian defectors living the dead end of the American dream in distant Oregon; unemployed, drowning in debt and refused the right to remain in the US by the immigration service because of their pasts but with nowhere else to go. All the while they live in fear of reprisals by former associates in Russia.

“This is not at all what we imagined when we went to the Americans. We don’t have jobs, we don’t have documents. We live in a place we never even heard of before we got here,” said Neumann. “I fucked up because I trusted the FBI. Do not trust anything to do with the US government because they will lie to you. They promise but they don’t deliver. There is no sense in cooperating.”

‘We could never go home’

In 2008, Neumann – or, as he was then, Aleksey Artamonov– realised it was time to get out of Moscow when his own father, a retired KGB officer, said “to shoot myself or they will do it for you”.

Neumann joined the FSB out of school, but after a decade in the security service, taking bribes but also watching where the real money was made, he moved to the shady end of banking as deputy head of security at a Moscow bank, Kreditimpeks. Part of his job, he says he told the CIA, was acting as the middle man in money-laundering deals with criminal gangs. Neumann describes a life flush with cash. Then, by his own admission, he “became too greedy”. His father’s warning was the signal to flee.

A Russian passport offers limited options for spontaneous travel. Most countries that do not require a visa are allied to Moscow and no place to hide. Neumann’s eye settled on an exception: the Dominican Republic. The couple landed one May evening in 2008 with two suitcases, $15,000 in cash and pictures of the life they had abandoned. They show Janosh with flowing dark locks and a taste for flowery shirts. He is chubbier than now, a reflection of the good life.

Photographs of Victorya reveal a poised elegant woman with a taste for idiosyncrasy. In one picture, posing outside a church in a sky-blue denim jacket, her hair is dyed orange.

Their most immediate concern was to disappear. Only later did they decide to defect.

“It was not a plan at all when we left Moscow. We never discussed it,” said Neumann.

Alone in the Dominican Republic, their options appeared limited. They couldn’t expect to go unnoticed on the island for long if the Russian authorities started looking. Still they hesitated to go to the Americans. Inside the FSB, in the old KGB headquarters in Moscow’s Lubyanka square, the US had remained “enemy number one”, as Neumann put it, long after the cold war.

He knew he would be branded a traitor, not least because he came from a family line serving the Russian state back to the tsar.

“It’s a really tough step. We served one country, Russia, and for us to make a decision to go with US officials, we technically became traitors the next minute,” he said. “We could never go home. You are betraying everybody who is believing in you.”

The Neumanns initially checked into a hotel in the beachside resort of Cabarete but then found a room in a villa. There, Janosh composed a letter.

A week after landing in the Caribbean, he walked into the US embassy in Santo Domingo and asked to speak to an intelligence official. A woman appeared. He showed his FSB credential and handed over the letter. They arranged to meet two hours later at a nearby cafe, Il Cappuccino.

“There were two of them,” said Neumann. “The woman was wearing a fake wig. It kept moving and she kept having to put it back in place.”

The agents first asked if the Neumanns had information about a threat to American lives. Janosh said he knew nothing about terrorism, explained his background and said he was looking to swap information for a new life in the west. The Americans asked about the couple’s motives and psychological state.

“Then they asked me, what do you have?” he said. “Financial corruption, and the connections between the Russian government and the Russian mafia there and in the US, and how the system is working with the bribing and the bank. The links to the FSB. How it all is tied together.”

One of the Americans handed Neumann $2,500 in cash.

At a second meeting two days later in a bookstore, a Russian-speaking intelligence officer asked if they knew of Americans spying for Moscow. Another agent took Neumann’s FSB credential.

The agents handed over $2,000.

There were eight meetings with the CIA over six weeks in June and July 2008. The agency gave them a cover story; they were advertising executives from Kiev.

One morning an American agent delivered them to a government office and waited as a Dominican official took them inside.

“I tried to say, hello, how are you doing?” said Victorya. “They didn’t want to hear my voice. They didn’t want to look at me.”

The couple emerged with Dominican Republic identity documents in the names of Andrey and Maria Bogden, Serbs born in Belgrade.

Family history

As the CIA sought to verify the Neumanns’ identities, Janosh poured out his family history. His father served in the KGB as a procurator. A grandfather spent the second world war as a colonel in Stalin’s intelligence interrogating Nazi soldiers because he spoke German. A great grandfather served the tsar’s secret police pursuing Bolsheviks before the 1917 revolution.

“Both lines, my mum’s line and my dad’s line, both were military or serving the secret police. It’s a family business. Some families got to work in a factory. Not us,” he said. “When I was a child, even my nanny was a soldier.”

So it seemed only natural that at the age of 17, the then Aleksey Artamonov should be sent for training at the FSB academy – what he laughingly calls “KGB high school”.

“My choice to join the FSB was not my choice. It was my father’s. We never had any kind of normal relationship as a son and dad. I was following all the time what he wanted me to do. There were two opinions at home – his and wrong,” said Neumann.

At 13, he was packed off to New York on an international exchange and a year later to Miami. His father later told him the visits were to condition him for the family business by helping to improve his English and getting to “know the enemy”.

As it turned out, Neumann liked the enemy. He enjoyed American culture. He felt freer.

“It was completely different to Russia, an open world,” he said. “My opinion about the US is not even close to my father’s.”

Neumann said he earned a master’s degree in criminal law at the FSB academy and was appointed second lieutenant. He specialised in counterintelligence and was posted to the financial crimes department where he pursued organised crime and investigated crooked bankers. Neumann also spied on foreign businessmen.

“We’d listen to their calls. We’d hear them phone their wives and then they’d be talking to their friends about picking up Russian girls. That kind of information is useful,” he said.

Neumann’s future was mapped out by his father but the two fell out after his first marriage, before Victorya, was to a woman “outside the KGB family”.

“My father’s plan was for me to go into foreign intelligence. That was always the path. He told me that’s why they sent me to visit the US. But after my marriage, there was no more talk of that. She was an outsider, not to be trusted,” he said.

Neumann said his FSB career ran into a wall. He had also seen a more lucrative path.

Neumann admits to taking bribes from corrupt banking officials when he was in the FSB’s financial crimes unit. He decided to flip over to the other side, quit the security service and took a job as deputy head of security at a Moscow bank, Kreditimpeks.

The former FSB officer told his CIA interrogators the bank oversaw a sprawling money-laundering operation on behalf of criminal groups and the rich. He said that through subsidiary banks it set up shell companies in Malta, Vietnam, the British Virgin Islands and the Baltic states where big firms, legitimate and criminal, could park their assets or launder money.

“The bank created the whole investment project,” he said. “And then it’s like a money hole. Money coming and coming. Technically if you’re reinvesting the money you don’t need to pay taxes. Or you’re creating a fake loan which says a Russian company owes money to a foreign company. You say you’re repaying the loan. That’s why the money is going from Russia to the outside.”

Neumann said the bank’s fee was up to 20% of the laundered funds and a cut was paid to his team of five men which did a lot of the legwork with underworld clients dealing in cash.

“I had a regular salary, five or six thousand dollars a month. But we could make tens of thousands of dollars every month in fees. The biggest single fee I made was $100,000. I was spending all this. Her lifestyle,” he said, stealing a look at Victorya who appeared none too pleased. “If she wanted to go to the store, I just gave her what she needed. A hundred thousand roubles. Two hundred thousand. I just picked up a block of money and gave it to her.”

Neumann told the CIA he was hired by the bank for his contacts in the Russian security service and remained a reserve FSB officer.

“FSB guys worked for us transporting cash. We used FSB credentials. Sometimes we used even government vehicles for this,” he said. “The whole operation is illegal. Completely. But for us, it was a business.”

The relationship with the FSB also forewarned the bank of investigations.

“We were paying bribes to the economic investigation department. We paid money to the organised crime units inside the police. Sometimes I was delivering the envelopes,” he said. “These guys were providing us with information. What kind of banks in Moscow were under investigation by these units. Who’s the next target for investigation. Who’s the next target for a search. Who’s being monitored by law enforcement.”

Neumann had his differences with his father but makes a point of saying he respects him as an honourable man who never took a bribe in his life and was dedicated to serving Russia and the communist cause. He blames his own corruption on the collapse of ethics with the end of the Soviet Union and the rush to make money in the 1990s. Although he says he is ashamed of taking bribes, he adds so many qualifications – almost everyone in government service is at it, my generation lost its ideals – that his remorse comes across as less than heartfelt.

Neumann also frankly concedes that the high life might have gone on had hubris not got a grip on him.

“We had so much money we felt like no one could touch us. No one could stop us,” he said.

When Kreditimpeks moved to buy a smaller bank to add to its collection of money-laundering fronts, Neumann and his men demanded 10% of a deal they had no hand in – a payout of millions of dollars.

“We got too greedy. We asked for too much and it went bad. They made the decision to move against us. The first I knew my bank accounts were frozen. Then the threats came. I knew we were in trouble,” said Neumann.

His father’s admonishment to shoot himself followed. Neumann suspects his father meant it. Janosh and Victorya made a run for it.

‘We never heard of Portland until we ended up here’

The CIA returned to each meeting with Neumann with ever more detailed questions. The Russian pressed the American agents about when they were going to get their new identities. He said the CIA discussed where the couple might go. The agents ruled out Switzerland but suggested Canada? The Neumanns wanted Sweden.

Then there was the money. Neumann said the CIA agreed a lump sum payment of $1.8m although it was never put in writing.

The debriefings continued until mid-July when the Americans suddenly said it would be safer to move to Puerto Rico, a US territory just to the east. They would go by boat.

The Neumanns boarded a catamaran around 3am on 16 July accompanied by a CIA agent. Hurricane Bertha passed through a few days earlier and was still churning up the Caribbean. The couple was sick most of the way and soaked to the skin.

Around noon, a US coast guard cutter took the Neumanns on board. The pair expected Puerto Rico to be the end of their journey but they were immediately driven to an airport and ushered on to a small jet, still in wet clothes. It was not until they were in the air that they discovered they were on their way to the United States.

“We had no idea we were going to be on that plane,” said Neumann.

A few hours later the couple landed in Virginia. On their first night in the US, they were taken for dinner by a Russian-speaking CIA agent. The Neumanns got drunk. Janosh told Russian jokes. No one talked business.

The next day three FBI agents arrived dressed in similar dark suits and looking, as Neumann describes it, as if they had stepped out of the film Men in Black.

“They sat opposite us in a row,” he said. “One of the first things they asked was, did you kill anyone? I was clear. No, never.”

The CIA brought the Neumanns into the country but they said the FBI swiftly embraced them as useful in investigating Russian organised crime with tentacles in the US.

The bureau’s lead agent on the case, whose first name is Karen (the FBI asked the Guardian not to publish her surname), a Russian mafia specialist, built an unusually close relationship with the couple, particularly Victorya, who said the two women held long, sometimes highly personal phone conversations and exchanged hundreds of text messages.

Meanwhile Neumann said the promises of a better future kept coming.

“The FBI assured us we would receive passports, social security cards, driver’s licences. That we would get certified copies of our Russian qualifications to use in the US so we could find jobs,” he said. “The Virginia FBI office said we could have a green card within a year if we cooperated.”

Then the FBI dropped the bombshell that the deal to pay the Neumanns $1.8m was off. Instead they would received a $300,000 lump sum, still a considerable amount of money. There was also a contract which paid the couple paid $3,500 a month each to assist with investigations.

The pair has steadfastly refused to discuss the details of their work for the FBI because the contract forbids it but there are clues in the wording which refers to Neumann as JJN.

“JJN agrees to assist the FBI in collecting evidence and intelligence against subjects,” it said. Neumann is required to communicate with suspects and wear a wire, and to read and translate documents.

In short, he was expected to help reel in his former comrades in arms in illegal banking deals and money laundering in Russia and the US. He has declined to say if his work for the FBI has resulted in prosecutions.

Victorya said she was used in a different capacity.

“I got together info remotely. Not on the Russian community. Both organised crime and terrorism,” she said.

After a few months, the Neumanns were moved again, this time to Philadelphia. After three months there, Karen flew the couple to Salt Lake City to appear before a judge and change their names. Neumann was asked to come up with a new name and settled on Janosh from the Roman god with two faces looking at the past and the future. He chose Neumann for “new man”.

“Afterwards Karen said, now we’re going to Portland. I said, where the hell is Portland? We never heard of Portland until we ended up here. What I know about Portland, it’s something between Seattle and San Francisco with a Ukrainian who plays for the basketball team,” said Neumann.

Between the US and Russia: an issue of cooperation

The FBI agent drove the couple to Oregon in November 2008 and settled them into Portland where they remain. Their contract was renewed each year but there was still no sign of the promised foreign passports so the Neumanns began pushing for American identity documents. Anything to be able to build a normal life.

“I asked, where are our documents and when can we go and do our thing? We’re tired. They tried to say they were working on it to find out which place is best for you and blah, blah, blah,” he said.

But the relationship was already beginning to sour. Neumann said the FBI began to describe him as uncooperative.

“They put in a report that I was threatening them and not fully cooperative,” said Neumann. He says the threats were not physical but to take legal action.

The issue of cooperation may be tied to his insistence that he would not talk about the FSB’s legitimate activities, only the illegal ones.

“I told them: I’m going to help you but I’m not going to do anything that crosses a line,” he said.

It was important to Neumann that he not be seen as a traitor to Russia, whatever his father might think.

“I never set up anyone from the Russian intelligence. I never screwed anyone with whom I was working. So no one was in danger because of me,” he said. “If I screw up gangsters, criminals, guys who are dirty, guys who are corrupted, I don’t give a shit.”

There was also a question of credibility. Some in the FBI doubted the veracity of the Neumanns’ information. There are hints in legal documents that the couple promised more than they could deliver. Some of the agents didn’t like their manner.

“A few times we heard that we stepped on some toes. They called us rude and pushy. They don’t believe what we are saying most of the time because we can’t prove it immediately,” he said.

Janosh said his information conflicted with some of the bureau’s long-held working assumptions to the embarrassment of some agents.

Victorya said Janosh had a tendency to be combative.

“A lot of times the word ‘arrogant’ was used and people don’t like arrogant people. You may be too arrogant. I heard that,” she said.

Certainly, Neumann can sound superior as he derides the FBI as “like a second-rate soccer team” and compares it unfavourably with the FSB. But if the Neumann’s credibility was part of the problem, events in Russia were to provide some corroboration of his claims.

***

Last year, Kreditimpeks’s banking licence was revoked over more than 13bn roubles in “suspicious transactions” during 2013 alone and for repeated breaches of financial regulations.

It followed a raid on the bank in 2013 over an 8bn rouble VAT fraud scam by six shell companies. The bank was accused of laundering billions of roubles through a property deal in Turkey. Kreditimpeks was also named in an official report as having received more than 600m roubles in stolen government money during 2009 and 2010.

After five years, the FBI cancelled the Neumanns’ contract without explanation. That meant the end of their visas under a programme for people cooperating with federal law enforcement and the loss of work permits. Without jobs, the money dried up.

Even as the relationship with the FBI grew more troubled, the one between Victorya and Karen became more intimate. Victorya shared her fears and troubles, including a health crisis in part brought on by the stress of life in exile.

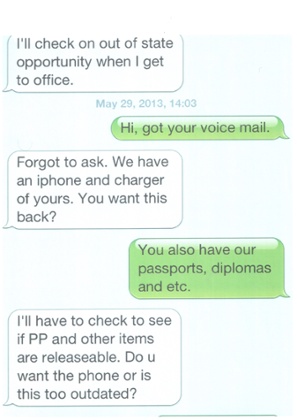

Much of the relationship is documented in hundreds of text messages Victorya has kept. Among them is one from May 2013, in which she told the FBI agent they were facing eviction from their apartment.

Victorya claimed she was owed a final payment of $7,000 for work done for the FBI, enough to cover the outstanding rent. Karen responded: “My agent is putting the payment request in today. I will push it through. We have the money.”

But the money did not come.

The Neumanns paid off the outstanding rent by selling their car but still had to leave the apartment because they could not afford the next month’s payment. They say they have sold many of their possessions and now rely on occasional part-time work and loans from a friend to keep the bills paid.

Still, the CIA and FBI gave them a $300,000 lump sum and paid them $7,000 a month for years – well above what most Americans earn. Where did it all go?

For a while the Neumanns continued to spend as they had in Moscow. They drove upmarket cars and lived in the expensive end of downtown Portland, in part because they did not have the identity documents and credit history required to rent through normal channels. But a good part of the money was sucked up by the US’s overpriced medical system as Victorya’s health collapsed under the strain of uncertain exile.

She guards the details but Victorya required a series of operations that cost more than $130,000 as well as long-term care she can no longer afford.

The Neumanns’ story at times seems so unlikely that one of their own lawyers, Judy Snyder, was hesitant to believe it.

“I had the initial scepticism that you might expect,” she said. “But with the multitude of documents there were pieces that were painting a fairly vivid picture which we corroborated partly.”

Snyder has seen the contracts with the FBI, also seen by the Guardian, which she is confident are genuine. The Neumanns also had copies of the Dominican Republic identity cards the CIA arranged and of Janosh’s FSB credentials.

“Everything that we could validate was validated,” she said.

Snyder hired a former FBI agent to poke around among old contacts in the bureau. He confirmed that the Neumanns had worked for the FBI.

“Based upon what we were able to validate, the behaviour of the US government was deplorable,” said Snyder. “They have been responsible for making commitments that have not been fulfilled and have basically abandoned Jan and Victorya after they have finished with them.”

Snyder struggles to explain the Neumanns’ treatment.

“My suspicions are that people made promises either they had no intention of fulfilling or promises that they were incapable of fulfilling. They didn’t bother about whether they were capable of doing it because all they cared about was getting the information that Jan and Victorya could provide,” she said.

“We had contact with several well-intentioned people who work for the government both at CIS [immigration service] level and the FBI level and the Senate level, people who really wanted to help, and even they were thwarted. The issue of who is placing the obstacles in Jan and Victorya’s path is not at all clear to me but it is certainly someone with enough power and authority to thwart even well-intentioned representatives of our government who are trying to help.”

Without papers to remain in the US, the Neumanns applied for political asylum. Months later it was refused in part because the immigration service said Janosh is a threat to US national security as a former intelligence agent of a hostile foreign power.

Snyder is scornful.

“If the government is interested in a person because of what they can bring to the table, and wants to bring them into the country because of those experiences and wants them to work for our government because of those experiences, how can they then say, well never mind we’re going to cut you loose without any assistance because of what you did in a foreign country? That’s ludicrous,” she said.

Asylum was also rejected on other grounds which are more tricky for Neumann. An immigration officer recorded that the Russian admitted to what Karen described in a text as “hurting people due to their political beliefs”.

Neumann vigorously denies this. The problem may lay in his use of English which is good but not always precise. Neumann said he was asked if he used force during interrogations as an FSB officer.

“He asked, are you doing anything physical? I said, not by myself. It’s not my job to do so. Of course I know how this looks like. I know how to do this. But I never do this by myself,” he said he told the immigration officer.

As he describes the interview, it becomes apparent that Neumann does not understand that the phrase “not by myself” can sound as if he was torturing a suspect in league with another interrogator when he meant to say he himself did not use force. But even with that qualification, it sounds as if he was present during torture.

Neumann may have compounded his problem by elaborating on his answer.

“I can ask 25 times the same question to a person. But for local guys, interrogation means using water, electricity, they cut their balls and ass. That’s what they’re doing. I said to him, I’m not doing this,” he said.

Asked why he would use an asylum interview to describe the FSB’s torture techniques and how he thought that would help his case, Neumann replied: “He asked a general question and I gave him a general answer.”

The immigration service also concluded Neumann discriminates against people based on their ethnicity. Asked why it would think that, he said he described Russian mafia as dominated by Armenians and Jews.

“It’s not my fault they are organised. It’s like in the US. Most of the mafia families are Italians. It doesn’t mean I hate Italians,” he said.

Karen called the asylum interview a “disaster” in a text to Victorya.

***

Although the FBI cut off the Neumanns’ contract, some of its agents felt they owed it to the couple to sort out the immigration issue. Karen arranged for one of the bureau’s lawyers to write the couple’s appeal but she warned Victorya it would almost certainly be refused again. Neumann is still awaiting the appeal interview.

Neumann eventually gave up on the FBI and hired Snyder who filed a notice of intention to sue against the bureau, the CIA, the Department of Homeland Security and the immigration service. It claims damages for false imprisonment on the grounds the couple was brought to the US without their consent and are unable to leave because the FBI refuses to hand back their Russian passports. The suit accuses the US government of fraud for allegedly failing to follow through on its commitments.

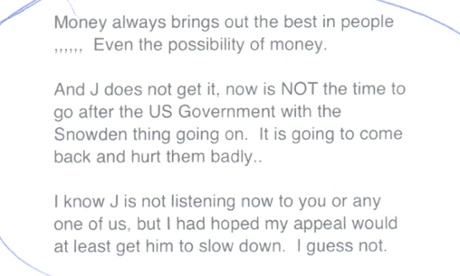

Neumann insists the legal action is not about the money. Karen thinks differently and warns Victorya that the timing is bad with Edward Snowden in Moscow following his revelations in the Guardian.

“Money always brings out the best in people ,,,,, Even the possibility of money. And J does not get it, now is NOT the time to go after the US Government with the Snowden thing going on. It’s going to come back and hurt them badly,” she said in a message.

In another text, the FBI agent writes: “J is an adult and the lawyer cannot protect him when his true identity is made public. Money will not help then. And even if the government pays, it will not be for years. A lot of permanent damage for short term gain.”

Karen also warns Victorya that suing the FBI may result in the release of her medical records which could make it harder for her to find a job.

But the FBI agent acknowledges the crisis the Neumanns are facing.

“I understand and i know the fear. Falling off the edge is a scary possibility,” she wrote.

Eventually, Victorya tells Karen that she has lost confidence in the promises of documents.

Karen replies: “I cant seem to make that happen.”

In desperation, the Neumanns turned to Oregon senator Ron Wyden, who sits on the intelligence committee. One of his staff, John Dickas, said in an email to the Neumanns that the FBI acknowledged its responsibility to help them win approval to remain in the US. But Wyden’s office has not had any more success than anyone else in discovering why the bureau soured on the Neummans.

Wyden’s spokesman, Keith Chu, said in written answers to the Guardian that “the senator’s staff have made inquiries to the FBI about this case, and continue to ask follow-up questions to get additional information”.

“The FBI has been somewhat slow to respond to inquiries about this case,” he said.

Chu said that Senator Wyden is also in communication with the immigration service “to resolve the Neummans’ asylum claim as soon as possible”.

Janosh stopped listening to the FBI’s warnings to keep a low profile. Desperate for work, he landed a small acting job in a television series set in Portland. This produced the unusual spectacle of a foreign defector, living undercover with a new identity, popping up in the nationally syndicated sci-fi police drama Grimm.

Neumann plays a heavy sent to abduct a woman from her hotel room. Dressed in a black suit with his thick Russian accent still in place, he does a passable impression of a mobster.

“Basically I just played myself,” he said.

Neumann’s appearance is fleeting. Within a few minutes he is shot dead.

Earlier this year, Karen sent a text to Victorya with the name of a New York lawyer, Michael Wildes, who has experience of representing whistleblowers, defectors and foreign diplomats collaborating with the US.

Wildes told the couple the FBI offered to pay his fees. He started work on their case but the payment from the bureau never arrived. So he stopped.

“There are a low of politics involved in all these law enforcement agencies. My sense, not just from this case but other cases, is everyone’s concerned about exposing their methods and procedures. There’s a delicacy involved,” he said.

“This is a family that put themselves in harm’s way for the protection of our interests in a very delicate region and should be given every deference for that. Both as a measure of gratitude and as a strong message to other people out there who would want to help America’s homeland security issues abroad.”

The Neumann’s have now retained Wildes themselves.

The FBI declined to comment. It said it does not comment on the use of specific informers. It is understood that individual agents continue to help the Neumanns on their immigration battle.

Janosh Neumann is as much bewildered and disappointed as he is angry. He expected better of the Americans because they are not Russians.

Once feted and charmed by the CIA and FBI as a valuable intelligence asset, he is struggling to understand how it is his future is being decided by an immigration service which holds him in no regard at all.

So was it a mistake to walk into the US embassy seven years ago?

“My big mistake was first to trust the bureau,” said Janosh. “To be honest with you, I had an absolutely different opinion about their professional level, about their dignity. This is a huge disappointment for me.”

Victorya’s frustrations are not only directed at US officials.

“Even though I’m very bitter and disappointed, I don’t think it was a mistake. For me, the mistake was to leave [Moscow] initially. It’s hugely different between why he left and why I left. I left for him. I didn’t leave because I had to leave. But we cannot go back,” she said.

Victorya said she feels badly let down by the FBI as a whole but is still uncertain about whether Karen was sincerely trying to help or playing them all along.

It’s unlikely the couple will be deported given their years of cooperation with the US authorities. They would almost certainly lose their freedom, and possibly their lives, if they were returned to Russia.

But their dreams of living the life they imagined defectors enjoy – having the run of Europe with new identities, invented histories and flush with money – are long gone. Instead they get to live like so many Americans, struggling to make ends meet, fighting off the debt collectors and worrying about the immigration service banging on the door.