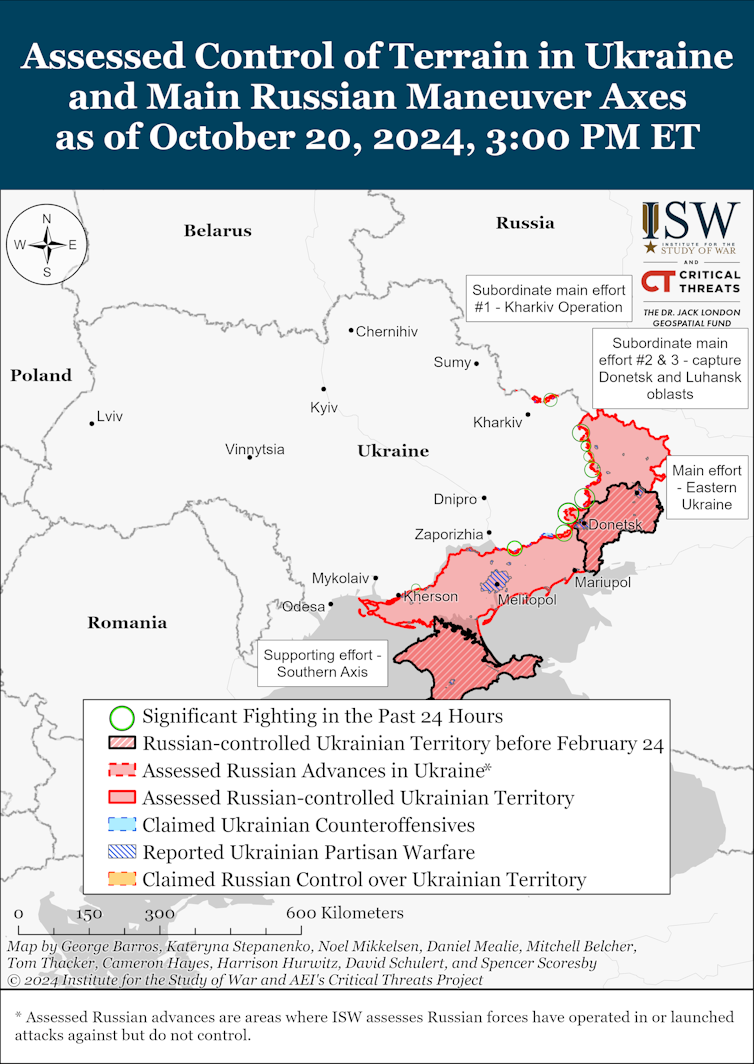

Reports have emerged in recent months of particularly savage casualties among Russian troops fighting in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine, as the Russian military bids to capture as much territory as it can, possibly with one eye on a potential ceasefire deal. Much will depend on the outcome of the US election. Donald Trump has said he will end military aid to Ukraine if elected, bringing the war to an end in “one day”.

This could mean that Kyiv will be forced to cede Ukrainian territory along current lines of occupation. Analysts have commented that this was one of the motivations for Ukraine’s Kursk offensive inside Russia in August, since territory captured by Ukraine would be a valuable bargaining chip in negotiations.

But meanwhile Russia’s offensive in eastern Ukraine has been particularly bloody, with US intelligence reports of casualty numbers of up to 1,000 per day, dead and wounded. This calls to mind the “meat grinder” tactics of previous Russian and Soviet military campaigns.

The “meat grinder” is a collective battlefield approach that values high troop density and intensity to overwhelm the enemy. It is a uniquely Russian approach nine decades in the making, consisting of a combination two much older strategies, namely attrition and mass mobilisation.

At the heart of attrition is the notion of abundance. The opponent is physically and psychologically exhausted by the sheer force of numbers, as wave after wave of cannon fodder are relentlessly deployed. Mass mobilisation is the large-scale movement of troops to a particular location with the intention of overpowering the adversary. Neither approach recognises the intrinsic value of individual lives.

Despite being outmatched in organisation and tactics, the Russian military successfully undertook a war of attrition against Napoleon’s invasion in 1812. A century later, the Russian empire generated enormous casualties but successfully launch large-scale counterattacks during the first world war.

The “meat grinder” became embedded in Soviet military tactics. The phrase “quantity has a quality of its own” has apocryphal roots in Stalin’s leadership during the second world war. Key battles such as Stalingrad and Kursk involved the deployment of millions of soldiers, and the Soviet army eventually crushed the Nazi blitzkrieg through sheer weight of numbers on the eastern front.

Past victories do not guarantee future success. But – for the Russian president, Vladimir Putin, and his military planners – it seems the dead and disabled bodies of their own soldiers are necessary collateral damage. It is estimated that more than 70,000 Russian troops have died since 2022. But it has been reported that Russian casualty rates are now rising more rapidly due to its military’s increased reliance on inexperienced fighters.

Civilian recruits now make up the greatest proportion of deaths since the invasion began. This increase is partially their lack of military knowledge in a challenging fighting environment against a highly motivated enemy. But inadequate medical care and poor quality protective kit are also important factors. The Russian state media shares carefully curated images and stories of the deceased but morale is still crashing, and military wives and mothers are rebelling.

Ultimate sacrifice

Putin’s meat grinder continues to expand, however. The Russian government announced plans to spend £133.8 billion on national security and defence in 2025, equivalent to 41% of annual government expenditure. All healthy men aged 18 to 30 can now be conscripted, and Russia has recently ordered a third increase in Russian troops. The recruitment of a further 180,000 soldiers will make Russia’s army the second largest in the world, with nearly 2.4 million members. Yet this army is unqualified and offers little protection for the individual soldier.

Ukraine does not view its soldiers’ lives as disposable in the same way – and they are comparatively well trained and resourced. But the dynamic in Ukraine may be changing. The country’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, signed new conscription laws in April 2024 that lowered the age of conscription to 25, and it has reached the point where eligible men are now being dragged away from restaurants and nightclubs by army recruiters.

Russia’s meat-grinder tactics are not infallible and will eventually collapse. Large formations can quickly become large targets in an age of remote reconnaissance. While Russia can coerce military participation through the carrot of high wages and the stick of forced conscription, a large and unmotivated army is not well-equipped for modern warfare and will eventually produce diminishing returns.

Even declaration of martial law in the whole of Russia – Putin introduced martial law in occupied part of Ukraine in September 2022 – would not overcome the deeply embedded structural issues Russia faces. Poor care of soldiers and veterans will generate long-term challenges in the form of disability and treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder.

The social and cultural harms of a poor culture of care are already manifesting in Russia. Approximately 190 serious crimes have been committed by veterans upon returning home. With Putin showing no interest in peace, we can only hope that the Russian war machine burns itself out – and that the long-term consequences are not terminal.

Becky Alexis-Martin is affiliated with the British American Security Information Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.