Editor’s note: This story was originally published January 28, 2018. We have republished it following Roger Federer’s retirement announcement Thursday.

Forget Tom Brady. Forget LeBron James. Forget Tiger Woods, if you hadn’t already. With a thrilling five-set win over Marin Cilic in the Australian Open final, Roger Federer, in the midst of the greatest late-career comeback sport has ever seen, won his 20th major and undoubtedly clinched his spot as the greatest athlete of his generation.

Federer, 36, had now won three of the last six Grand Slams. He’s the best tennis player in the world, again, at an age when Pete Sampras had already been retired for a half-decade. His longevity is stunning: When he returned to the winner’s circle at last year’s Australian Open, it was supposed to be an epilogue to a tremendous career. Turns out it merely started another chapter.

How rare is Federer’s mid-30s dominance? In the past 45 years, only five men have ever won a Slam while older than 30 years, 10 months. None won multiple titles past that age and the oldest among them was aged 32. Federer, on the other hand, has four titles since hitting that age – almost as much as everybody else who’s ever picked up a racquet since 1973, combined. He has three Slams since turning 35 when no one of this, of the previous era, had one older than 32. It’s another assortment of firsts for a player who’s been setting them since 2003.

With all the recent success, it’s hard to remember just how impossible this all seemed as recently as 13 months ago. Yet the doubting of Roger Federer started long before that.

At the start of this decade, Federer was already widely considered the greatest tennis player in history. With his sublime footwork, picturesque backhand and an unparalleled on-court genius, Federer won 11 of 17 of Grand Slams from 2003-07 and then five of the next 10 after that. Overall, from the 2003 Wimbledon through the 2010 Australian Open, Federer won 16 of 27 majors and played in the finals of six more. Amazingly, for a seven-year stretch, there were only five majors that didn’t feature Roger Federer on the final Sunday.

And then Federer turned 30, an age at which some athletes (quarterbacks, basketball players, soccer stars) are hitting their prime while others (running backs, Olympic athletes and tennis players) are on their way over the hill. Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic were five years younger than Federer and hitting their strides just as Federer was fading. The new guard was in and Fed, like so many before him, would likely fade into the tennis ether. Players simply didn’t last this long. Federer knew this as well as anyone: At one point in 2009, he announced that making it to the the 2012 London Olympics was a goal of his.

He was to be an ancient 30 years old at those Games.

After he won the 2010 Australian Open, Federer went nine majors without a win (and eight without playing in the final), prompting endless questions about whether he’d ever get another major to his name. When he ended that noise by winning seventh Wimbledon in 2012, tying his idol Pete Sampras for most all time, it merely started the cycle anew. “Could Federer ever win again (again)?”

The general consensus was that he couldn’t. Federer would keep playing his graceful brand of tennis to some success – win some tournaments, make another deep run or two in a major, but that was it. Thirty-year-olds simply didn’t hang around that long. Federer might be able to stick with Nadal, Djokovic and Andy Murray for a little longer, but even the extraordinary Swiss master couldn’t keep Father Time on the run forever.

That was six years ago. And in in the interim it got way worse before it got better.

In 2013, Federer fell to No. 7 in the rankings – his first time out of the top three in a decade. He lost a shock match in the second round of Wimbledon, snapping his record streak of 36-straight Grand Slam quarterfinals. In three of the next four majors, he’d fail to reach the quarters and his ranking would fall to No. 8 – a place it hadn’t been in 12 years.

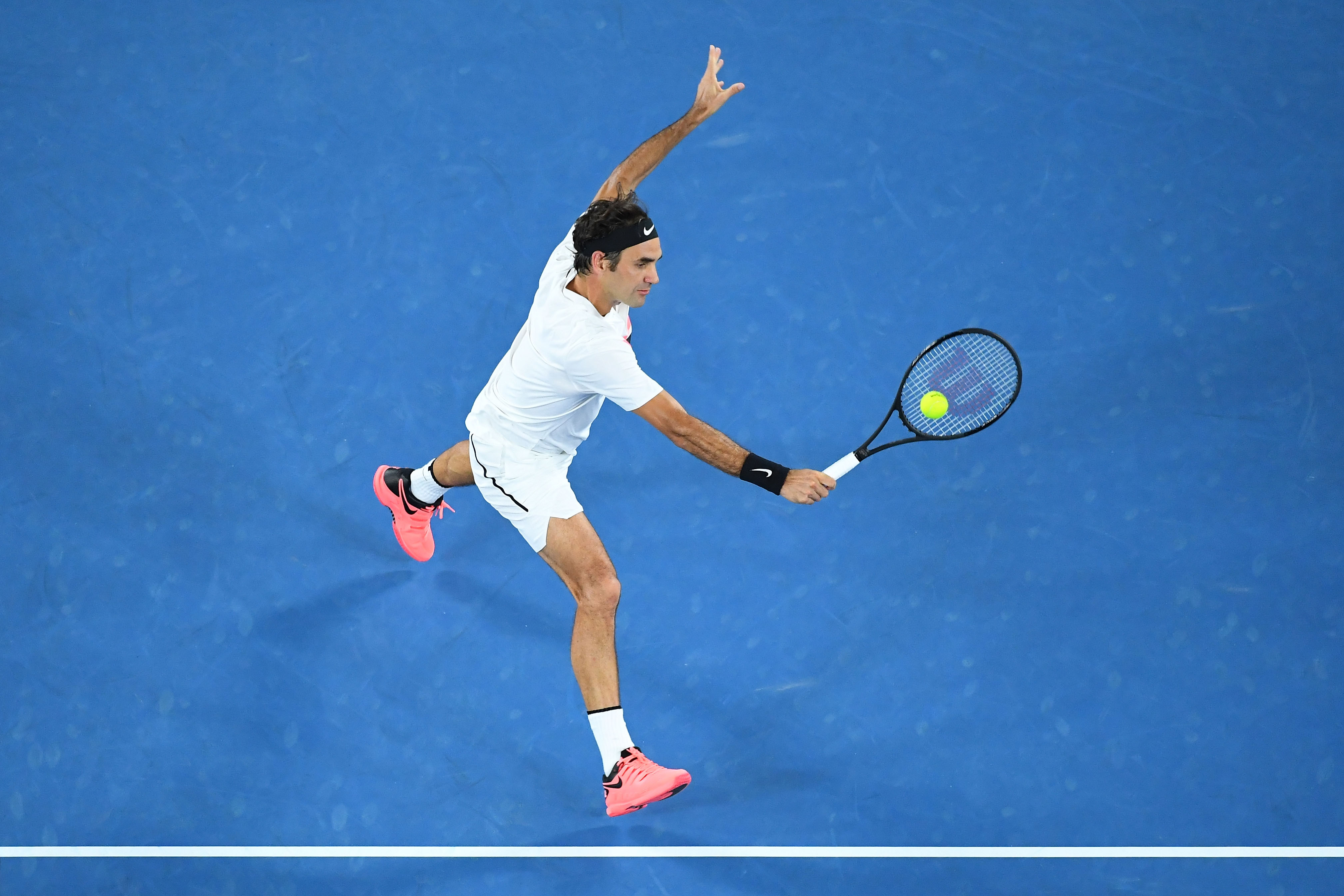

But Federer modernized his game – changing to a 97-inch racquet head that would purportedly give him more power, if less control. After a grace period, Federer was able to get both power and control and soon he was whipping his classic one-handed backhand like it was his heyday. Along with a Steph Curry jump shot, the Federer backhand is the most beautiful sight in sports. Firm, but smooth. Powerful, but controlled. He manipulates the ball as if the racquet was an extension of his hand. (When Federer said in a press conference that he wouldn’t teach his kid the one-hander, it prompted Chris Clarey of The New York Times to liken it to Da Vinci telling his kids not to draw.)

Federer was competitive in a few Grand Slam finals during that time – all losses to Djokovic, who was now the immovable force Federer used to be – but he was playing well enough where it was realistic to think that if he got a favorable Grand Slam draw and saw some of his rivals drop out early in the tournament, he could get one more title before hanging up his racquets.

Then the injuries started. Federer, who had played in a record 65-straight majors, slipped while giving his daughters a bath at the 2016 Australian Open and had to miss that year’s French Open. A comeback at Wimbledon almost got him to the final, but the back trouble from that accident in Melbourne proved to be too much to overcome and Federer made the unprecedented move of sitting out the rest of the season off to recuperate. He’d endured the rigors of 15 endless tennis seasons. Perhaps the break would reinvigorate his game. Or perhaps his career would be felled by the same back issues that had ended so many before him.

It was the former. By a lot.

Federer made his Grand Slam return at the 2017 Australian Open and, ranked No. 17, looked fresher than he had in a decade. He won the major, his first in nearly five years. The predicted recipe for a title (hope some rivals lose, play short matches and ride an easy draw to a title) was thrown out in Melbourne as Federer played three of the world’s best in the final three rounds and went to five sets in each. In the final, he met his arch-rival Rafael Nadal in a match that may have had more riding on it than any other in history. With a win, Federer would win Slam No. 18, extending his record and finally snapping his drought. If Nadal won, he’d get his 15th, just two behind Federer. With his requisite win on the red clay of Roland Garros, Nadal could have been on Federer’s heels, just one Slam behind, and suddenly the G.O.A.T. debate would have been up for grabs once more. (The Spaniard also extend his career dominance over Federer – which has been in a sticking point with the anti-Fed faction who ask how Federer can be the best if he can’t beat Nadal?)

Down a break in the final set, Federer stormed back to beat Nadal, got on the winning side of that two-Slam swing and set off one of the most stunning seasons in tennis history. Federer won both springtime American hard court tournaments (beating Nadal both times and changing the entire tenor of that rivalry), had his best start to a season in 11 years, then unorthodoxly skipped the entire clay-court season, dominated the field at Wimbledon without dropping a set and then played strong to close the season. He finished 52-5 with two Slams, three Masters 1000 titles and his best winning percentage in 11 years (and his fourth-best ever).

He entered this year’s tournament in Melbourne as the favorite and the only healthy member of the Big Five. (Andy Murray was out while Djokovic, Nadal and Stan Wawrinka were compromised.) At 36, he was the freshest of all. Federer survived the carnage that saw other top seeds fall in every round and made the final against Cilic, the tall, powerful Croatian who beat Federer in the 2014 U.S. Open semifinal (when the draw had opened up and Federer looked like he’d finally get that elusive major) but was bested by The Fed in last year’s Wimbledon final.

Federer took the first set with ease, lost a tiebreak in an even second set, cruised in the third and then went up a break in the fourth. He was three games from another major. And then it all fell apart. Suddenly, Cilic looked like he did during his U.S. Open title run and Federer had the uncertainty and doubt that had plagued him during his down years. When the Swiss was experiencing his semifinal and finals losses at majors back in 2013-16, it wasn’t because he was getting run off the court, it was because he couldn’t get the big point at the big moment. He was almost allergic to break points then. When his serve abandoned him in the fourth set, the crowd at Rod Laver Arena – rabidly pro-Federer, as crowds always are – went quiet. It was happening again. Federer couldn’t locate a first serve, Cilic had him moving and a fifth set would be a dogfight in which Cilic seemed to have the upper-hand.

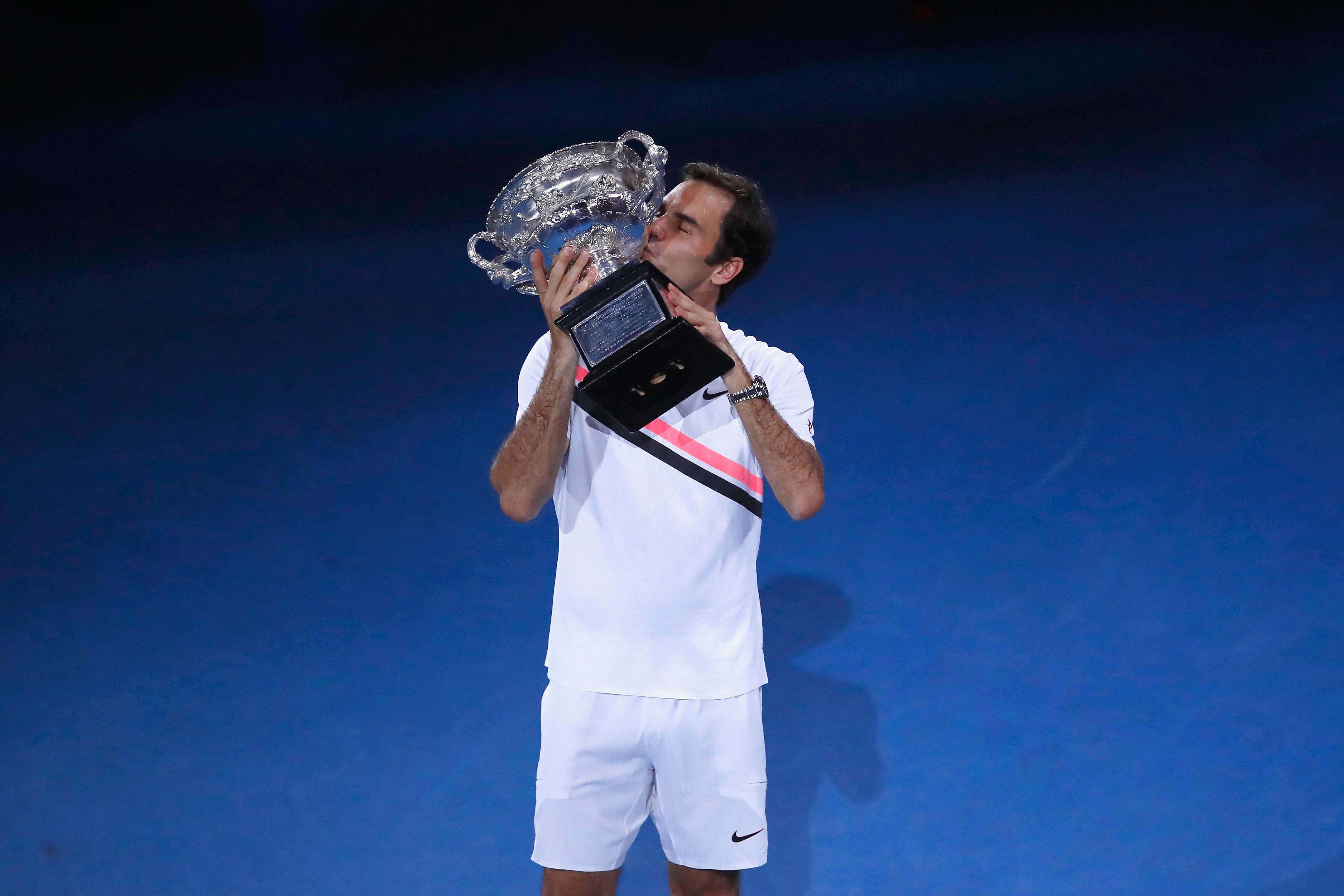

But after saving two break points in his opening service game and breaking Cilic the next game, Federer cruised to a 6-1 final-set win, his victory only delayed by a last-shot challenge (just like it’d been in 2017 against Nadal). Was it more remarkable that Federer is the second-oldest Grand Slam champion ever (and the oldest in 45 years) or that it would have been a major surprise if he wasn’t?

This Australian Open was the 200th Grand Slam played in the Open era (which began in 1968). Federer has won 20 of those, or one out of every 10. He’s won three of the last six. Since he was supposed to be washed up at age 30, Federer has won four majors. Meanwhile, no player born in 1989 or later has ever been the victor at a Grand Slam. Those players could be as old as 29 now, the same age Federer was when the whispers first started as his tennis mortality.

No career in any sport can compare. The dominance of the early years coupled with the unexpected resurgence in the twilight. It’d be like if Jack Nicklaus had won the ’86 Masters and then followed it up with the ’86 U.S. Open, ’87 U.S. Open and a few player of the year awards.

There are other once-in-a-generation athletes currently playing other sports. One will be on center stage next Sunday, as 40-year-old Tom Brady goes for his sixth Super Bowl title. LeBron James may not be Michael Jordan, but that’s always been far too casually thrown around as an insult instead of a celebration that LeBron is even in the same conversation. Tiger had the greatest run that this sporting generation has ever seen, but it was eight years of magic followed by eight years of pain.

Each of those other greats has a “yeah, but” attached to their case. Brady’s success is tied to Bill Belichick’s, which isn’t a knock, it just makes them more of a G.O.A.T. team than G.O.A.T. individuals. (Imagine Brady without Belichick and vice-versa. One is Aaron Rodgers the other is Bill Parcells. Hall of Fame worthy, but not historic.) Then there’s LeBron, who hasn’t been his best on the big stage and has suffered from his indecisiveness. Tiger – well, you know what happened with Tiger.

Yet Roger Federer persists. He looks as fresh at 36 as he did at 26 and plays with an intensity and appreciation that can only come with perspective gained by a player who almost saw it all disappear. Federer knows he’s one stumble away from a back injury that’ll ruin his career and plays like it. But it’s not a tentative game; Federer is playing like it’s okay that each point might be his last. He’s content with it.

The win in Melbourne allowed Federer to successfully defend a Grand Slam title for the first time in a decade. At the end, he wept, an emotional release for all the self-doubt that followed the greatness, all the greatness that followed the self-doubt and the appreciation that maybe he won’t ever again be standing at center court holding a trophy aloft.

But the last time Federer wept on the court after an Australian Open final, he’d just lost to Rafael Nadal, capping a six-month period in which Nadal had defeated him in the greatest tennis match ever played (which snapped Federer’s record Wimbledon winning streak at five tournaments and 41 matches) and then another Slam final in Melbourne. At the time, the speculation was that Federer could see the end was coming. Nadal was younger, faster and fitter. Federer was on his way to 30. The end was in sight.

That was nine years and a sporting lifetime ago.