Netflix recently announced it has acquired the rights to some of Roald Dahl’s best known works and intends to adapt them into a new animated series.

The streaming giant secured the blessing of the writer’s estate, managed by his widow Felicity, and intends to “expand” a number of his stories for the screen, including Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, The BFG, Matilda and The Twits.

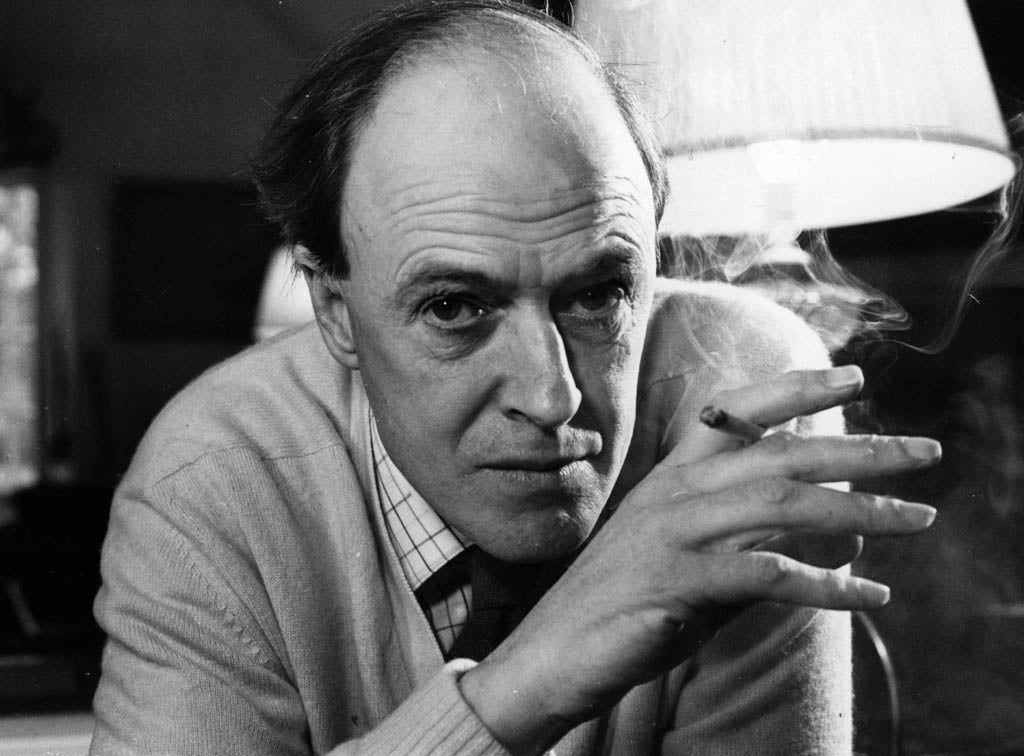

The author, who passed away in 1990, had served as a fighter pilot in the Second World War and went on to write several of the most loved children’s books of all time, selling more than 250m copies worldwide. His partnership with Quentin Blake was as inseparable a marriage of author and illustrator as that between Lewis Carroll and John Tenniel or AA Milne and EH Shepard.

And yet Roald Dahl was also a highly complex character, as the Royal Mint’s decision to scrap a commemorative coin in his honour attests.

We hold Enid Blyton to account for the more regrettable attitudes revealed by her prose and should not spare Dahl the same scrutiny. Nor should we allow the man’s personal failings to overshadow his adored body of work, one of the most remarkably inventive in the history of English literature.

Dahl’s novels are often dark affairs, filled with cruelty, bereavement and Dickensian adults prone to gluttony and sadism. The author clearly felt compelled to warn his young readers about the evils of the world, taking the lesson from earlier fairy tales that they could stand hard truths and would be the stronger for hearing them.

With this extraordinary writer in mind, here’s our selection of his 10 finest works.

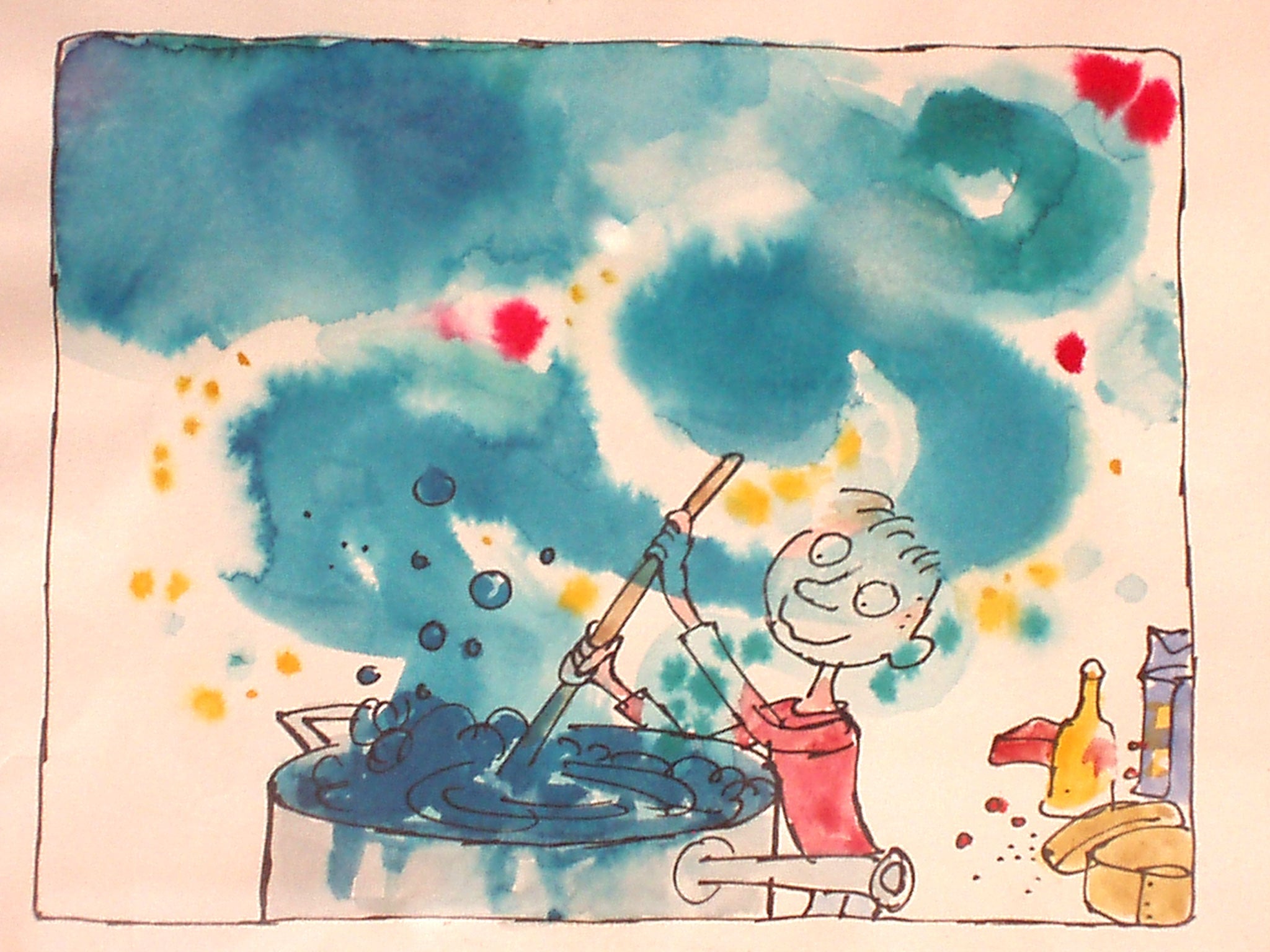

10. George’s Marvellous Medicine (1981)

The story of George Kranky, who concocts his own miracle elixir from deodorant, shampoo, floor polish, horseradish sauce, gin, brown paint, engine oil and anti-freeze to replace his tyrannical grandmother’s regular prescription dose in the hope of improving her mood. Dahl’s book had to be issued with a disclaimer warning children not to try this at home.

The author himself ignored the caution, however, enjoying a game with his own family wherein he would mix strangely-coloured drinks from milk, peach juice and other cordials, pretending the result was a magic potion.

Anticipating Matilda in encouraging children to take revenge on their adult tormentors with practical jokes, it also owes a debt to the “Drink Me” episode in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) in blowing up the aged relative to the size of a farmhouse.

9. Danny the Champion of the World (1975)

Expanded from a short story Dahl had published in The New Yorker in 1959, Danny tells the story of a boy growing up with his father William, a garage attendant, in a gipsy caravan beside a wood.

Danny discovers his parent has a sideline as a pheasant poacher and vows to help him catch the entire local flock before the squire, Victor Hazell, can stage a shooting party.

A moving tale of rural poverty alleviated by sudden inspiration, Dahl’s description of the countryside is based on the hills and farmland around Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire, where he lived, and the resulting work has something in common with Barry Hines’s A Kestrel for a Knave (1968) in its portrait of boyhood sorrow and loneliness.

Dahl himself owned a Romany wagon much like that described in the book, and wrote the novel sat inside it at the bottom of his garden. It was often a makeshift playroom for his children.

8. James and the Giant Peach (1961)

Dahl often wrote about youngsters whose parents are suddenly taken away from them in shocking circumstances: in the case of James Henry Trotter, his are run down by an escaped rhinoceros during a shopping expedition to London.

Consigned to live as a de facto slave with his cruel aunts on the White Cliffs of Dover, James is given a bag of “crocodile tongues” by a mysterious old man who promises they will bring him joy and adventure. The boy duly spills them in the garden, causing a peach to grow to enormous proportions and eventually roll out to sea, taking James with it.

James befriends the eccentric insects living inside it and together the group lash its stem to a flock of seagulls, who fly the peach across the Atlantic to New York City, where it is speared atop the Empire State Building.

A fantastic flight of invention, riffing on Jack and the Beanstalk, Jonathan Swift, surrealism and perhaps even the promise of LSD at the dawn of the psychedelic Swinging Sixties, James and the Giant Peach may be Dahl’s wildest creation.

7. Boy (1984)

This memoir recounts the author's childhood growing up in Llandaff, Wales, the son of Norweigian parents, and traces his young life through to the end of his tenure at private school and his setting out for a job with Royal Dutch Shell in Tanzania.

Boy is a superb document of life in the Britain of the 1920s and 1930s, but is also highly revealing about the genesis of the writer’s obsessions. “The Great Mouse Plot” - detailing an eight-year-old Roald and his friends hiding a dead rodent inside a gobstopper jar at the local sweetshop to upset its unpleasant owner, Mrs Pratchett - could have come from one of his novels.

The violent reprisal, in which Roald was caned by his headmaster while Mrs Pratchett looked on with grim approval, seems to have shaped his unforgiving view of adults thereafter.

Dahl would continue his biography with a second book, Going Solo (1986), recording his war service with the RAF.

6. Fantastic Mr Fox (1970)

Like Danny the Champion of the World, Fantastic Mr Fox is another story drawn from the countryside near Dahl’s home, concerning a roguish father getting one over on local landowners.

Mr Fox’s raiding missions on the poultry and cider stores of villainous farmers Boggis, Bunce and Bean (“one fat, one short, one lean”) give us nature red in tooth and claw. One moment in which its chicken shack Robin Hood protagonist loses his tail to a shotgun blast is particularly traumatic.

Wes Anderson made a handsome stop-motion animation of the book in 2009, voiced by George Clooney and Meryl Streep. He stayed in Dahl’s famous writing shed to compose the screenplay and gave Mrs Fox the maiden name “Felicity” in tribute to the author’s wife, whom he befriended.

5. The Twits (1980)

A highly misanthropic entry, The Twits recounts an arms race between an unhappily married couple, each bidding to humiliate and traumatise the other through an ever-more cruel series of pranks.

Mr Twit’s attempt to convince his wife she is shrinking by adding an extra sliver of wood to her cane every night is as good an illustration of gaslighting as you will ever see, an extraordinarily dark piece of psychology to have included in a book for children, even for a writer as unflinching as Dahl.

A passage about the unpleasant personality of Mrs Twit eroding her once-attractive face into ugliness is especially fine, while his repulsive description of her husband’s filthy beard attests to a life-long loathing of facial hair. The poet Michael Rosen told BBC Radio 4’s Word of Mouth in 2016 that the writer had once lambasted him for his own on the set of a TV show.

4. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964)

Perhaps Dahl’s most widely read book, Charlie captures its author’s own childhood love of sweets – as discussed in Boy - and provides a vehicle for his uncompromising personal morality.

When reclusive confectioner Willy Wonka suddenly announces a plan to include golden tickets inside the wrappers of his chocolate bars, permitting the holder to tour his factory, the promotion creates a media sensation. Against the odds, the impoverished Charlie Bucket finds one and follows the other lucky recipients through the gates.

For all the wonder Dahl conjures in his description of the chocolate river, Inventing Room and Oompa-Loompas, the novel also carries a decidedly sinister undercurrent, unfolding like a slasher film as the other children are effectively bumped off one by one as their faults and flaws are made apparent, leaving Charlie the last boy standing.

The characters are highly memorable and superbly named - Violet Beauregarde, Veruca Salt, Augustus Gloop - and, in Mike Teavee, Dahl offers a satire of materialistic American youth obsessed with screens that was decades ahead of its time. His sequel, Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator (1972), is even more eccentric.

3. The BFG (1982)

Roald Dahl always had a fascination with wordplay, working out the optimum pun, neologism or nonsense coinage in draft before settling on the definitive version.

Rarely was his use of language more playful than in The BFG, in which the titular Big Friendly Giant speaks in a tongue known as “gobblefunk”: “I know exactly what words I am wanting to say, but somehow or other they is always getting squiff-squiddled around.”

The giant catches dreams in bottles and adopts Sophie - a heroine named after Dahl’s first grandchild - after the girl learns of his existence, taking her on an adventure involving “snozzcumbers”, “frobscottle” and plenty of “whizzpopping”. They encounter rival giants who eat “human beans” and end up at Buckingham Palace to appeal to the Queen for the arrest of said brutes.

2. The Witches (1983)

Unquestionably the writer’s scariest book, this tale of a boy and his cigar-huffing Norwegian grandmother encountering an international conference of witches at a luxury hotel in Bournemouth drew on Dahl’s Scandinavian heritage to flavourful effect.

His characterisation of the harpies – bald, square-toed, pearly-eyed – lives long in the memory, as does the grandmother’s haunting tale of a childhood friend trapped for all time inside a painting.

The Grand High Witch’s genocidal plan to wipe out the children of the world with poisoned confectionery reads like a perversion of Willy Wonka’s golden ticket scheme, while the narrator’s being turned into a mouse looks all the way back to the author’s own youth as described in Boy, that book itself inspired by his having commenced work on The Witches.

It was brilliantly adapted for the screen by the late Nic Roeg in 1990, with Anjelica Houston and Mai Zetterling ideally cast, the former unforgettably grotesque as the Grand High Witch in her true form.

1. Matilda (1988)

Matilda is a child prodigy and precocious reader inexplicably born to the uncouth and profoundly crooked car salesman Harry Wormwood and his vain wife Zinnia.

At school, she encounters the perfect teacher Miss Honey - who immediately recognises her gifts - and the tyrannical headmistress Miss Trunchbull, a sadistic former track-and-field athlete with a penchant for flinging girls like a shot put.

Learning the (deeply sinister) truth about the two women’s shared past, Matilda conspires to help her sponsor and bring down her tormentor with the aid of newly discovered telekinetic powers.

An ode to the joys of reading and an unabashed celebration of the intellect triumphant, Matilda sees Dahl express his black-and-white view of adult behaviour more explicitly than ever.

Hugely popular, Matilda has run as a West End musical since 2010 and this year inspired a statue staring down Donald Trump and Quentin Blake to return to his easel to imagine the grown-up Matilda on the book’s 30th birthday.