If the pre-election budget was designed to address the cost of living, it missed something. In an effort to help those whose wages aren’t growing as quickly as prices, it offered

a one-off A$250 payment to income support recipients

a temporary increase in the low-and-middle-income tax offset

a six-month halving of the fuel excise

But it failed to offer help to some of the Australians who need it the most.

Australians only spend 3 per cent of their incomes on petrol. The typical renter spends more than 10 times as much on rent.

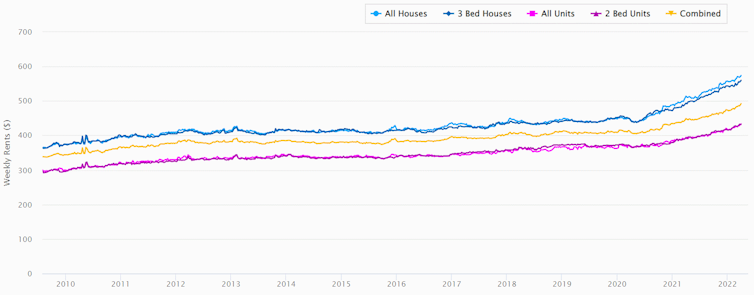

After a minor and temporary reprieve early in the pandemic, advertised rents are again on the rise – up nearly 10% over the last 12 months.

Weekly rents, national

Low-income renters are especially hard hit. More than half suffer rental stress, meaning they spend more than 30% of their income on rent.

One-third have less than $500 of savings on hand in the event of an emergency.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison has responded to complaints about rent by saying the “best way to support people renting a house is to help them buy a house”.

Cutting deposits can’t cut it

Morrison points to the federal government’s decision to more than double the size of the Home Guarantee Scheme, which helps people buy a home with less than the standard 20% deposit.

From this year, up to 50,000 people will be able to access the scheme, under which the government offers a guarantee to the banks that cuts the up-front deposit to 5% for ordinary first home buyers and just 2% for 5,000 single parents. There are 10,000 places reserved for regional house buyers.

Read more: The compelling case for a future fund for social housing

The expanded scheme will help some Australians buy their first home earlier, but for everyone else looking to buy a house, the extra demand created by the scheme risks pushing up prices even higher.

And many renters won’t be able to find even the 5% deposit. Five per cent of $600,000 is $30,000.

Rent assistance assists less

If we really wanted to help low-income renters, we would boost rent assistance.

Commonwealth Rent Assistance is paid to pensioners, other beneficiaries and those receiving more than the base rate of Family Tax Benefit Part A who rent in the private rental market or community housing.

Paid at the rate of 75 cents for every dollar of rent above a threshold until a maximum, it works out at up to for $72.90 a week for a single and $68.70 for each member of a couple.

Read more: $1 billion per year (or less) could halve rental housing stress

It hasn’t kept pace with rent. Boosting it by 40%, (roughly $1,450 a year for a single), would restore it to where it was in relation to rent, albeit at a substantial cost – $2 billion per year.

If the new rate was linked to the rents low-income earners actually pay, rather than to overall inflation as it has been, renters would be protected in the future.

Some argue this would lead to higher rents. But that’s unlikely. Most low-income renters first pay what’s needed to put a roof over their heads, then use what they have left to cover food and other bills, rather than offering more rent.

Rents needs properties

The other thing governments can do is to increase the number of homes.

Australian cities are not delivering denser forms of housing – townhouses and apartments – in the quantities Australians say they want.

The people who already live in a given suburb usually want it to stay as it is, whereas the people who would like to live there don’t get a say because they can’t vote in council elections. Their interests are left unrepresented, meaning housing isn’t built where it is needed.

Read more: Older women often rent in poverty – shared home equity could help

The Commonwealth can help drive change by offering the states incentives tied to how well housing supply keeps up with population growth.

This will only reduce rents slowly, but low-income renters stand to gain the most since they are the first to lose out in the scramble today, just as they seem to have lost out in the pre-election budget.

Grattan Institute began with contributions to its endowment of $15 million from each of the Federal and Victorian Governments, $4 million from BHP Billiton, and $1 million from NAB. In order to safeguard its independence, Grattan Institute's board controls this endowment. The funds are invested and contribute to funding Grattan Institute's activities. Grattan Institute also receives funding from corporates, foundations, and individuals to support its general activities, as disclosed on its website.

Brendan Coates does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.