Today marks 15 years since David Blaine was hoisted above London’s River Thames in a small Perspex box with only water and barely enough room to stand up and lie down.

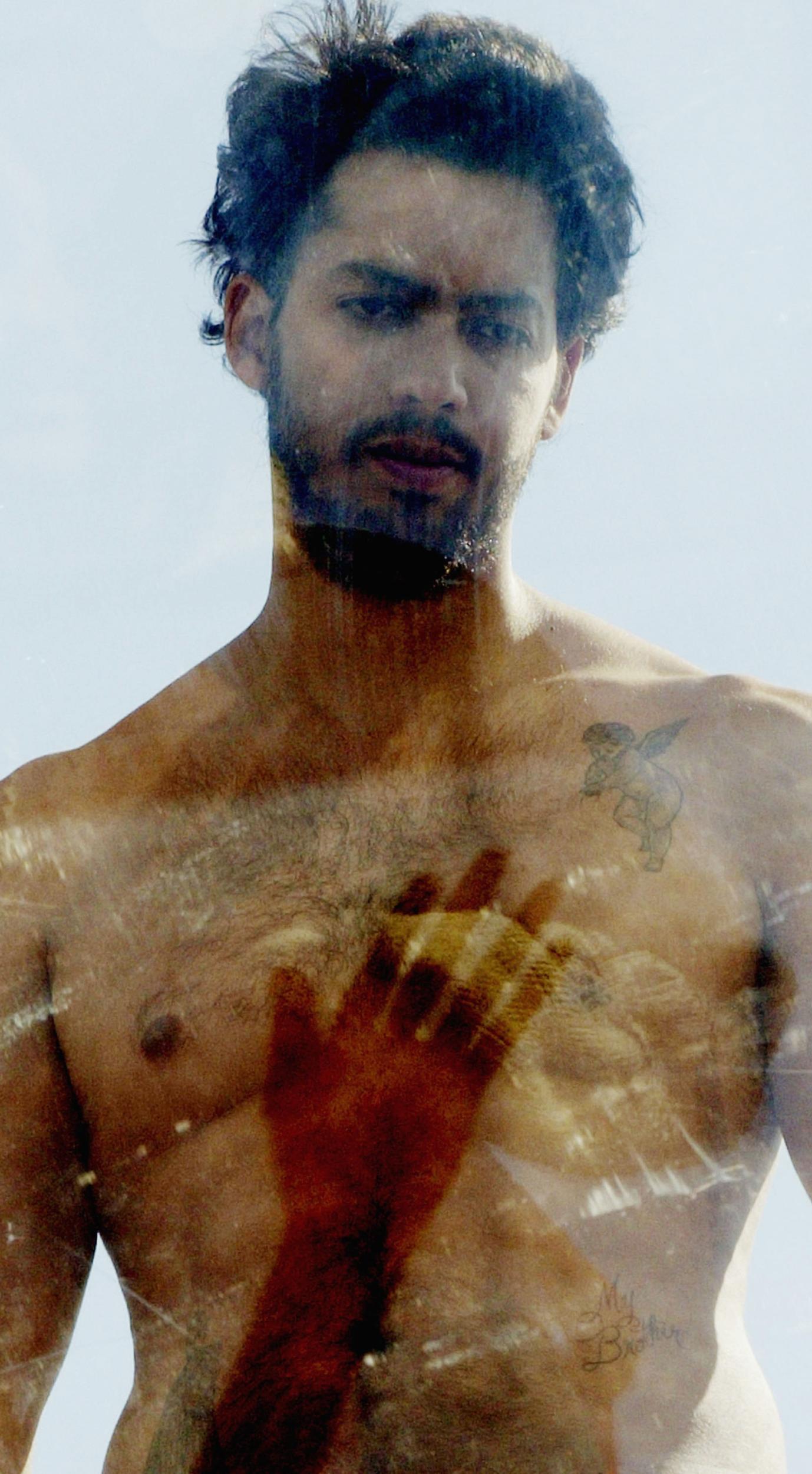

He would stagger from the 3ft by 7ft by 7ft box 44 days later – bearded, gaunt and 60 pounds lighter – with symptoms of starvation including depleted organ and bone mass, heart palpitations, breathing problems, and loss of skin pigmentation. In the final days of his self-inflicted captivity he could taste pear drops, a medical quirk caused by ketones produced when the body is forced to begin burning its fat reserves.

Or so he said. Blaine’s street magician background presented a fundamental roadblock to his forays into performance art throughout the 2000s, assuring that his feats of endurance – from being buried alive to encased in ice – were always met with scepticism. With a webcam constantly observing him in the box, few doubted that Blaine did indeed spend the full 44 days inside it, bar a few fringe theories involving holograms and body doubles. More plausible suspicions about his “starvation” spread though, including speculation that his water supply was laced with nutritional glucose and sodium supplements. He denied them all. But even if there were a few secret helping hands along the way, you can’t deny that nearly two months of solitary confinement and no solid food is still a pretty astonishing feat.

Blaine underestimated the cynicism of the British public, though. During his box residency, Blaine was pelted with eggs and paint-filled balloons. Golf balls were struck in his direction from Tower Bridge. Drummers kept him awake at night. Tabloids, ever sceptical of anything characterised by the words “postmodern” or “performance art”, seized upon the stunt, staging appetite whetting barbecues beneath Blaine and even flying a hamburger up to his box with a remote-controlled helicopter in order to taunt him.

“We think the stunt’s really poor – it’s just rubbish. 44 days of this is just boring,” 33-year-old north London web designer Jason Robinson told the BBC at the time. Robinson was so angry about the stunt that he helped set up a (sadly no longer accessible) website named Wake David that was dedicated solely to crowdsourcing ideas for how to do just that.

The UK’s “Blaine-baiting” became international news. Hollywood trade mag Variety reported in a news story entitled “Illusionist gets a rude U.K. reception” that Blaine wasn’t receiving the “oohs and ahhs” he was used to on home soil. In fact, it claimed, members of the gay community were in

Genuine peril arrived on day 10, when a man staged a before-dawn raid on the box. While accomplices distracted security guards, the man scaled the tower supporting Blaine’s box and tried to sever the pipe supplying water to it. “Go home David, go back to America. We don’t want you here,” he reportedly shouted at the illusionist, grabbing the cage and announcing: “I’m going to rock you.”

These incidents don’t show the British public at their best, but some cynicism over the stunt was understandable. His previous stunts included spending 35 hours standing atop a 100ft pillar in New York’s Bryant Park and 64 hours entombed in ice down the road in Times Square. The fact that Blaine was cheered through these had as much to do with the less controversial and metaphorical nature of these stunts as it did with differing national demeanours. Electing to starve, while millions around the world had no choice but to, was a bold and provocative move, especially given that Blaine made no explicit attempt to politicise the stunt nor relate it to the issue of world poverty.

Instead, the reasons he gave for undergoing the potentially fatal stunt oscillated between morbid fascination with death, a kind of Buddhist exploration of simplicity, and plain old attention-seeking.

“I consider it a piece of performance art, and I also consider it something that for me is like the ultimate truth,” he said at a pre-self-imprisonment press conference notable for its conclusion, when he responded to a journalist’s request for a magic trick by swiftly severing part of his ear. “When you live with nothing there’s no distractions, you’re just there as you are, struggling; I think that’s the purest state you can be in.”

Going darker in behind-the-scenes footage, he offered this explanation: “I love the idea of death and I hate life, so these [stunts] really make me feel great. And I love making people watch suffering because I had to watch it my whole life – watch people I loved and were close to deteriorate and die ... I saw everybody I knew, my mother, my father, drop dead. I feel the most alive when I’m going through these experiences.”

It was Blaine’s apparent God complex that most people latched on to though. This reading of the stunt was not helped by its supercilious title, Above the Below, nor his response to how he’d like to be remembered if indeed the challenge did claim his life: “As the greatest showman of all time.”

This is not to say that all Brits were unsupportive. At any one time there were dozens surrounding the box to cheer him on or pin messages of encouragement to the guard-fencing. One onlooker even set up a chess match beneath the box, providing Blaine with some much needed brain stimulation as he relayed moves to the ground below.

It was this wave of positivity that Channel 4 rode with its live coverage of Blaine finally exiting the box. A curious hour of television awkwardly bereft of a presenter (below), it consisted of supportive vox pops from members of the public spliced jarringly with a short film on Blaine’s 44 days of suspension created by experimental filmmaker Harmony Korine. Returning from an ad break, you weren’t sure whether you were going to be met with – from the broadcast – Barry from Watford offering pop platitudes on the nature of determination or – from the film – shots of Blaine with blood spilling from his mouth and performing card tricks surrounded by naked gyrating women all set to noise rock guitar riffs. Though it no doubt came across as pretentious to anyone contemplating carpet bombing Blaine and his box with hot dogs, the film was at times actually quite moving.

“If you live until day 44 and then die on day 60, what’s the f*cking point?” an advisor warned Blaine in candid footage of his pre-stunt preparations, referring to the fact that the real danger and threat to life came not so much with the starvation (witnessed by the public) but the refeeding process (endured in private).

The short also conveyed the delirium caused by solitary confinement, Blaine experiencing blurred vision and hallucinations, and at times laughing or crying or both. Narrating his journey as though in a poem, he discussed the profound connection to simple things he experienced when life’s distractions were stripped away, like the sun’s rising and setting, and the quotidian life of the people below it. Inscrutable and aloof a person though he is, it was hard not to feel slightly in awe of him and his resolve.

Blaine’s isolation was very of its time, and though The Times reported that “1,614 articles in the British press made reference to the exploit” that year, this pales in comparison to the number we would see had it taken place today. In 2018, it would have been experienced almost entirely through Instagram Stories and live blogs and think pieces, an assessment of its worth being made without the thought to actually visit and look the man in the eyes.

It’s easy to forget just how much of a household name David Blaine was 15 years ago and how polarising a figure. He was, at the height of his powers, magic’s Kanye West; a magnet for attention and outrage, loved and loathed in equal measure by both the public and his peers. He’d make for an entertaining biopic one day, as it’s hard to discern his sincerity from his showmanship or square his self-hatred with his solipsism. These contradictions are perhaps most stark in his remarks that closed Above the Below, made as he headed, shaking, to hospital in an ambulance:

“What do you do when your death wish exceeds your life wish? What do you do when you love life but all you dream of is dying? Can you dream of the darkness when the rainbow flies? Whether you like me or not, whether you desire in secret or openly for my demise, I just laugh.”