To his nearly 200,000 followers on Instagram, Raven Smith speaks in what could be termed “gay internet”: dry, lusty, disillusioned, pictures of celebrities make up much of his feed. His captions read like howls of ironic despair and source the universality buried in pop culture camp. “Christmas shopping on a budget,” he writes alongside an image of Winona Ryder shoplifting. “SUNDAYS” appears next to a slide of Trinny Woodall in a cloud of cigarette smoke. There’s Victoria Beckham in a lab coat. Cassie in Euphoria looking wrecked. The bored it-girl who fell out a window in Sex and the City. Princess Diana. Princess Diana. Princess Diana.

Smith is also a Vogue columnist, red carpet fixture and bestselling author – his 2020 book Trivial Pursuits anatomised the mini, ludicrous traumas of modern life. And now his latest essay collection grapples with the most omnipresent mammal that isn’t actually talked about very much: men. Who are they? Why are they? Where did we find them? Raven Smith’s Men is about the males that have come to define his life. There are tales of fathers, boyfriends, perverts and Ken dolls; porn, steroids, sports teams and lads. It’s as wise as it is bawdy; the chain-smoking baby of Eve Babitz and Kim Cattrall. In tone, it feels like an astute, elevated version of Smith’s Instagram feed, something he’d hoped for.

“If you’re online all day being funny, which I am,” he says with a wink, “there is a feeling of being misunderstood. When I was at school, people wouldn’t take me seriously because I was funny. I hated it, so for a while I became more and more serious. It felt like the only way to prove that I was smart.” A few days ago, he had a conversation with his husband about why Raven Smith’s Men had come about. “Did I write this whole book to prove I don’t just do jokes? But he’s like… ‘The book is funny, though.’”

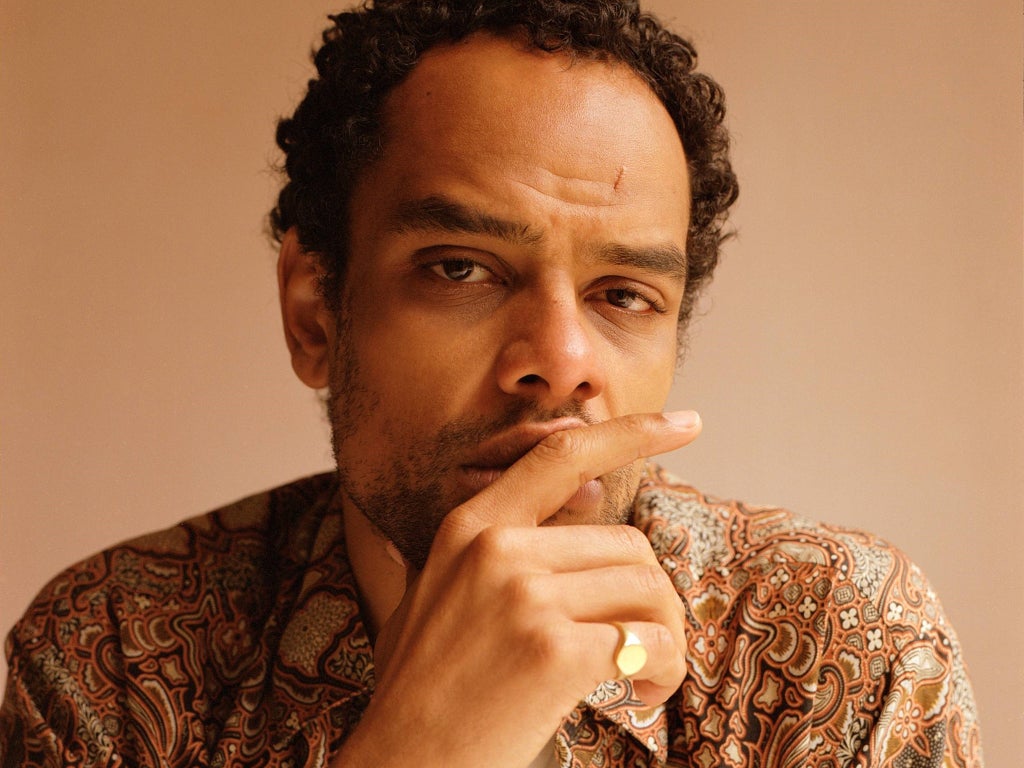

We meet at an art gallery cafe in south London where Smith – who’s been 32 “for several years”, according to his bio – is road-testing a new ensemble ahead of a forthcoming holiday. He has a process. He wears a few sartorial standards – white tube socks, a tailored trouser and always the same brand of navy-blue sneakers – alongside a shock of something new. Photographs of different looks will be taken and contrasted with one another, like a lo-fi version of Alicia Silverstone’s virtual wardrobe software in Clueless. He’s mulling his pistachio T-shirt. “It’s a bit younger than I would normally wear,” he explains. “But I think if I wore it with a pearl, it’d be quite nice for daytime, or a kind of beachy hotel?” He thumbs it, thoughtfully.

I ask him why men are usually so chaotic. “A lot of traditional masculinity is this mixture of power and dominance,” he suggests. “You’re only allowed to show aggression, and that conditioning is hard to break.” He says this navigation of our baser instincts applies, on one level or another, to all men. “I’m a smart, intelligent being, but also like a chimp full of testosterone.”

Raven Smith’s Men came to Smith like a detective story. He wanted to crack the mystery of manhood. “The most important people in my life are women, but I don’t lie awake at night asking why women are the way they are. I guess it’s genetic narcissism. How do I be a man? Am I not doing it right? It’s like men are a club I was born into that I still don’t f***ing get.” Plus, he could hardly write Raven Smith’s Women. “It sounds quite Peter Stringfellow, doesn’t it?”

I’ve repeatedly been told I’m not like other boys. I just accept that now

Something Raven Smith’s Men isn’t is a trauma memoir. Smith grew up in Brighton, the only child of a white mother and a Black father, who split up shortly after he was born. He writes that his childhood was “fine”, his psychological tablecloth “fairly spill-free”. His years of pretending to be straight as a teenager were more anthropologically fascinating than scarring: “Horny and grim,” he says of his heterosexual male friends at the time. “Such base-level, dick analogy chat.” He feels similarly distant from other mini-traumas that happened after. Yes, he is “slightly estranged” from his father, who once called him a disappointment, and he’d sometimes drink to excess in his twenties, and his flatmate died by suicide. But in person and in his book, there’s little finality to any of it, no clear-eyed summing up of what are very complex situations. Things happen. Shrug emoji. “No one ever puts a nice bow on it,” he explains. “Accepting that is why I’m happy.”

How did he get to a point where he’d describe himself as “slightly too self-assured”? He says it’s about balance. “What makes me happy is not pretending I’m not sad. Sad things have happened to me, but they’re not who I am. They’re just part of who I am. People ask me sometimes why I’m so confident. I think it’s just acceptance. From an early age, people have questioned my identity. At school, I was brown and all my classmates were white. Being a gay man is like being an outsider of both masculinity and femininity and yet inhabiting the characteristics of both. I’ve repeatedly been told I’m not like other boys. I just accept that now. We are all those moments.”

For a minute, I feel like I’m speaking to Oprah, or the final boss of total clarity and self-belief. But something keeps nagging at me – surely things must rankle him? “Oh, yeah,” he replies. “I have nemeses. And no one gets under my skin like another gay man.” Let’s parse that, I interject. He lets out a glorious cackle. “I don’t have that kind of relationship with women. I can fall out with a woman and quickly make up with them. It doesn’t hit the same when I fall out with gay men, in terms of how I feel about myself.” He notices that I’m intrigued. “Yeah, it’s murky.” That laugh again. “My relationship with gay men has always got an edge to it.” Is it a sense of competition? Or envy? “It’s not as simple as that. But also…” He sighs. “When I was 21, all my gay friends slept with each other all the time. But none of them slept with me. So I was like… hang on a minute. It’s not like I wanted to sleep with them, but I felt like an outsider to it.”

In Raven Smith’s Men, there is a brief aside stuffed towards its climax in which Smith admits to always having “this underlying feeling that I’m not pretty, not in a conventional way”. We know that beauty is subjective, that capitalism is “set up” to make us all feel like gremlins, but that – deep down, in our quietest, most cringeworthy moments – some of us do wish we could spend a day being, as he writes, “catalogue hot”. It struck me as a rare acknowledgment of men actually thinking about their own sexual desireability, or lack thereof. And a level of vulnerability unusual for a book climate that seems to have decided that being a man starts and ends with men’s rights bogeyman Jordan Peterson eating from troughs of meat. It’s less immediately funny than when Smith writes about faking an orgasm the first time he got handsy with a boy, but it’s also truer, messier, and certainly more frightening to ever admit.

Smith circles his empty coffee cup with a spoon. He reiterates that this kind of thing washes over him now. “All these things that should feel bad, they don’t feel bad to me any more. The thing I’m most proud of is not quite fitting into a box. I’m not traditionally masculine or traditionally feminine. I’m not white like half my family, and not Black like the other half of my family. Those are the things I like the most about myself, even if they’re the things that gave me the most anxiety when I was young. I don’t carry those things now, like I’m not enough.”

I’m still not entirely convinced, but later I ponder why I was trying so hard to unravel the mystery of Raven Smith, despite what felt like his total candour. And if, in a sense, I’d reiterated his thesis. Maybe, if you identify as a man, all you do is try to crack the mystery of being a man. How you do it, how others do it, and how hard it is to just accept ourselves for who we are. It’s like the patriarchy has given us all the apparent tools we need, but no instructions on how to use them. And thank god someone has come along to make us not feel so alone with that.

‘Raven Smith’s Men’ is in shops now via 4th Estate Books