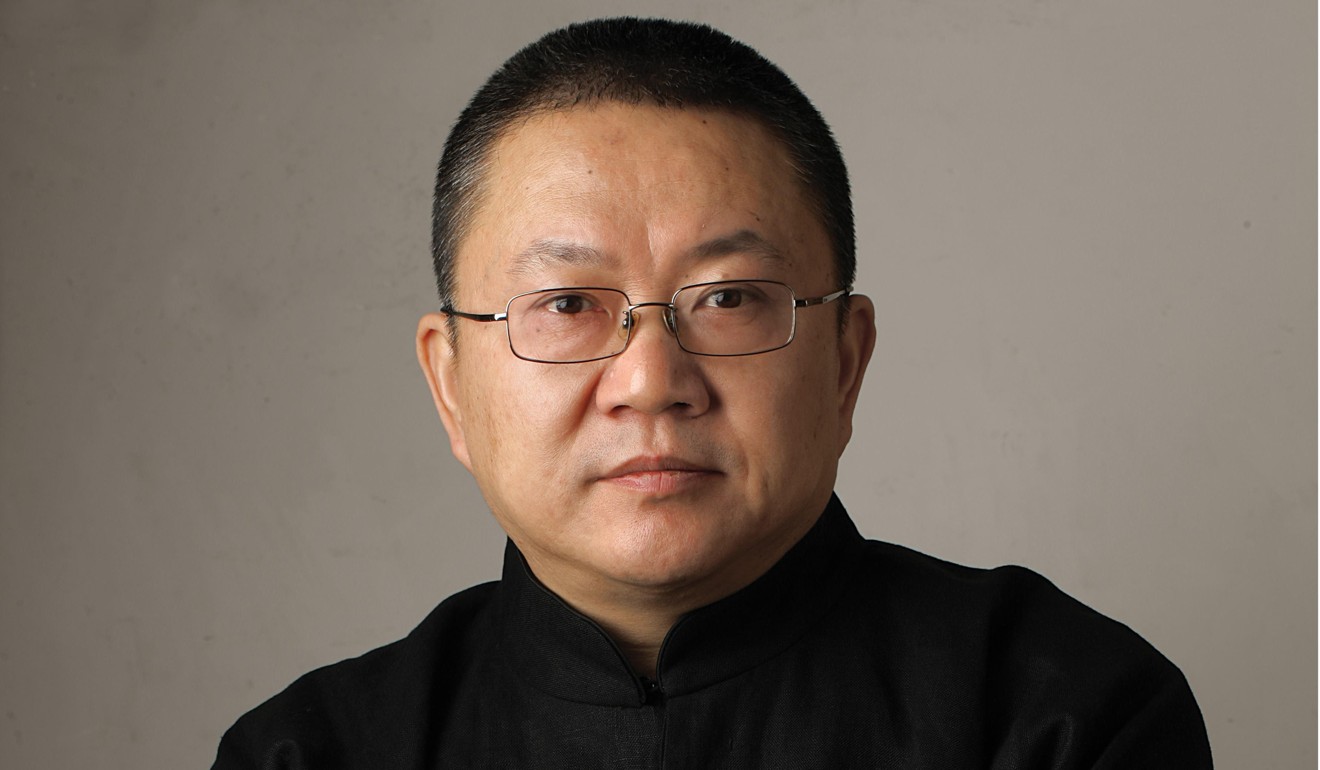

Wang Shu’s rejection of what he calls “professional, soulless architecture” has almost become a war cry. That kind of architecture, he believes, is ruining China.

“We are the largest construction site in the world, but the majority of materials used are concrete and steel,” he says. “There is almost no place for handmade, traditional and natural materials. But we are committed to turning that around. We want to bring back manual construction into modernisation.”

How architects are changing high-rise life with amazing balconies

Wang’s rebuke of rampant modernisation, and the self-described “contemporary traditional” style, has gained his practice an international audience. It has struck a chord with the French in particular, which is why a major retrospective of his and his wife Lu Wenyu’s work is currently on show in Bordeaux.

Even the name of the architecture firm they founded in 1997 draws from their rebel-with-a-cause ethos. “We called it Amateur Architecture Studio because, in China, we have a lot of professional architects, but almost no good architects,” Wang says, chuckling softly. “Secondly, our Chinese tradition lies not in professional architects but the history of craftsmanship, which is quite different.” That’s why he prefers the title “artisan” to “architect”.

Wang also calls for the safeguarding of China’s threatened countryside against what he describes as the sweeping destruction of history and culture in the rush towards urbanisation. In 2012, he even became the first Chinese citizen to receive the Pritzker Prize, architecture’s most prestigious award, for his standpoint on the issue and for his commitment to reviving traditional craftsmanship. The jury cited his ability to transcend the usual past-versus-future, traditional-versus-modern divide in producing architecture that was “timeless, deeply rooted in its context and yet universal”.

As he rallies to the cause, Wang believes education is critical. He and his wife have taught at Hangzhou’s fine arts school, the China Academy of Art, since 2000, and Wang is now the school’s dean of architecture. In 2002, the couple started to design a new school campus on the city’s outskirts. Wang describes the Xiangshan Campus, completed in 2002, as “an experiment in trying to influence the city with the countryside”.

That mission may be of universal relevance, and is gaining the couple increasing worldwide recognition, but, according to Lu, they remain marginalised in China.

“Huge agencies monopolise the system there, employing thousands of workers on large-scale mega projects that are not of a human scale and are really bad for the environment,” she says. “And we don’t want to be part of that.”

Wang has also been a visiting professor at Harvard University in the US, and has given guest lectures everywhere from the Singapore University of Technology and Design to the University of Hong Kong. His work has been exhibited at places including the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2016 and Denmark’s Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. At the latter his work was part of a new series of exhibitions dedicated to “pacesetting and prize-winning architects”.

The current retrospective in Bordeaux – the first show for Amateur Architecture Studio in France – is billed as this summer’s “major exhibition” at Arc en Rêve, an architectural centre committed to cultural and environmental guardianship in the fields of urbanism and design (the centre’s name is a play on words that means “dream architecture”).

Francine Fort, director of the centre, says the pair’s thoughtful resistance appeals to tradition-loving French people.

“In China, intellectuals were resistance fighters and they paid steeply for that,” she says. “Now Wang Shu and Lu Wenyu are fighting to stop the wholesale construction that is destroying China.”

Under the vaulted cathedral ceilings of the centre’s grande galerie, the show spotlights five key projects by Amateur Architecture Studio, including models of some of the 30 buildings of the Xiangshan Campus made with materials brought from China.

Wang, who visited Bordeaux with his wife in July, calls the couple’s 9,000 square metre (97,000 square foot) campus a “big village”. It comprises a series of small buildings including peaked-roofed studios for individual professors, as well as a tea house, meeting centre and guest house.

In signature fashion they used traditional Chinese building materials such as natural stone, wood and bamboo, which were combined with textured concrete and recycled bricks and roof tiles.

“We invented a new construction system by adapting artisan building techniques to a more contemporary style,” Wang says. “In the walls we used 40 different sizes of salvaged materials. This new way of craftsmanship makes students realise just how much of a rich mix they can use in projects.”

He says they were successful in going beyond the usual separation between city and countryside, adding that his driving vision is to translate the countryside to cities.

“A richer, more diverse world lies in the countryside. We want to recover different ways of building, and re-establish the relationship between buildings and nature. At the Xiangshan Campus you can look out and see the buildings’ relationship to each other – they are having a dialogue with each other like village buildings.”

Also on show at the Bordeaux exhibition are two Amateur Architecture Studio projects from China’s eastern Zhejiang province that made waves at the 2016 Venice Biennale: the continuing regeneration of the isolated village of Wencun, west of Hangzhou city, and construction of the newly opened Fuyang Cultural Complex.

Wang says he accepted the job of designing the Fuyang Cultural Complex, a sprawling 40,000 square metre art gallery, history museum and archive centre in Fuyang district, on the basis that he would be able to redesign and conserve the rural village of Wencun about 30 miles away. Around 30 other villages in the area, he says, had been demolished in recent years.

Inspired by the mountainous landscape, he built two dozen new houses around the surviving buildings that incorporated the traditional wa pan technique of mixing different stones and bricks in the walls to create stability, while creating rustic textured facades.

“For me the most important thing was to make buildings in scale with the surrounding environment, and to ensure they have a close relationship with local materials and craftsmanship,” Wang says.

Lu says the same wa pan recycling technique was used in the Ningbo History Museum, a structure designed by the couple that opened in 2008. “The artisans used stones, bricks and other debris – up to 1,500 years old – gathered from the ruins of nearby villages to make the [soaring angular] facades of the museum,” she explains.

Despite Wang’s love of craftsmanship, he rejects overly quaint reinterpretations of tradition. As he says in the Bordeaux exhibition literature: “Reducing tradition to a decorative symbol and then applying it to the surface of a modern building is precisely what kills the true meaning of tradition.”

At the Fuyang Cultural Complex, the huge multi-peaked roof mimics the mountain silhouettes in the background as well as traditional Chinese pagoda architecture.

Wang compares the complex’s design to a landscape painting, the same analogy he uses for the Xiangshan Campus with its surrounding lakes and forest. Nature – clearly his wellspring of creativity – is all around, he says, adding: “Our long history in China is rooted in the countryside.”

Five unfinished projects designed by late architect Zaha Hadid

But Chinese culture and history are fast vanishing because of unbridled development. Wang says 90 per cent of the country’s built heritage has already disappeared, including many of his projects from the 1990s.

“The countryside is in the process of becoming the city,” he laments, adding that future construction could help China hang on to its past if his message gets through.

“I learn from the countryside to try to influence city people, so then they will maybe understand that [urbanisation] is not just about high-rise buildings.

“China has a big chance to keep hold of what’s left … but if they don’t take care and turn the current situation around, all will be gone within a decade.”

The Wang Shu, Lu Wenyu exhibition runs until October 28 at Arc en Rêve, Entrepôt, 7 Rue Ferrere, Bordeaux