Detective Charles Smythe, deputy inspector Seymour Pine and six fellow officers from the New York Police Department (NYPD) entered the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village in the early hours of Saturday 28 June 1969 little realising they were about to make history.

“Police! We’re taking the place!” they barked, barging their way through the double doors of 51 and 53 Christopher Street as the establishment’s patrons rolled their eyes in exasperation. Another shakedown.

The bar, a well-known hangout for the city’s fledgling gay community, was an easy mark for corrupt officers.

Dubbed “Lily Law” or “Betty Badge” by their prey, these officers could pick up a weekly payoff from the owners - the Genovese crime family - in exchange for turning a blind eye to its serving drinks without a liquor licence and not leaking the names of influential customers to the press. The envelope of cash they pocketed in return for their compliance was known as “gayola”.

The Stonewall Inn had once been a stable. It had no running water to wash its glasses, no fire exit and the toilets frequently broke but it was a haven for the city’s outsiders, a sanctuary from a conservative state that considered their very existence a threat to public decency and national security and where dancing was permitted for a $3 entrance fee.

Its clientele was mixed-race but primarily comprised of gay men, although some lesbians and homeless teens sleeping rough in nearby Christopher Park often visited, drawn to the inclusive party atmosphere within its walls, painted black.

The cops usually tipped off the bar before carrying out one of its semi-regular raids, but this time refrained.

One theory was that the Stonewall Inn’s Mafia owners had begun extorting rich customers, particularly Wall Street traders, realising there was more money to be made from selling their silence than mixing drinks. Doing so, the theory goes, estranged the authorities from their kickbacks, prompting them to shutdown the bar permanently in revenge.

Smythe, Pine and their plainclothes team walked in on a crowded dance floor of some 205 revellers that balmy summer night - which happened to follow the day musical star and gay icon Judy Garland had been laid to rest - and barred the doors.

But their attempts to line up and frisk those patrons they intended to take into custody met with unexpected resistance.

The Stonewall’s cornered customers had simply had enough of being persecuted, refusing to hand over their ID cards or co-operate with officers seeking to verify the gender of cross-dressers, an intrusive and dehumanising routine.

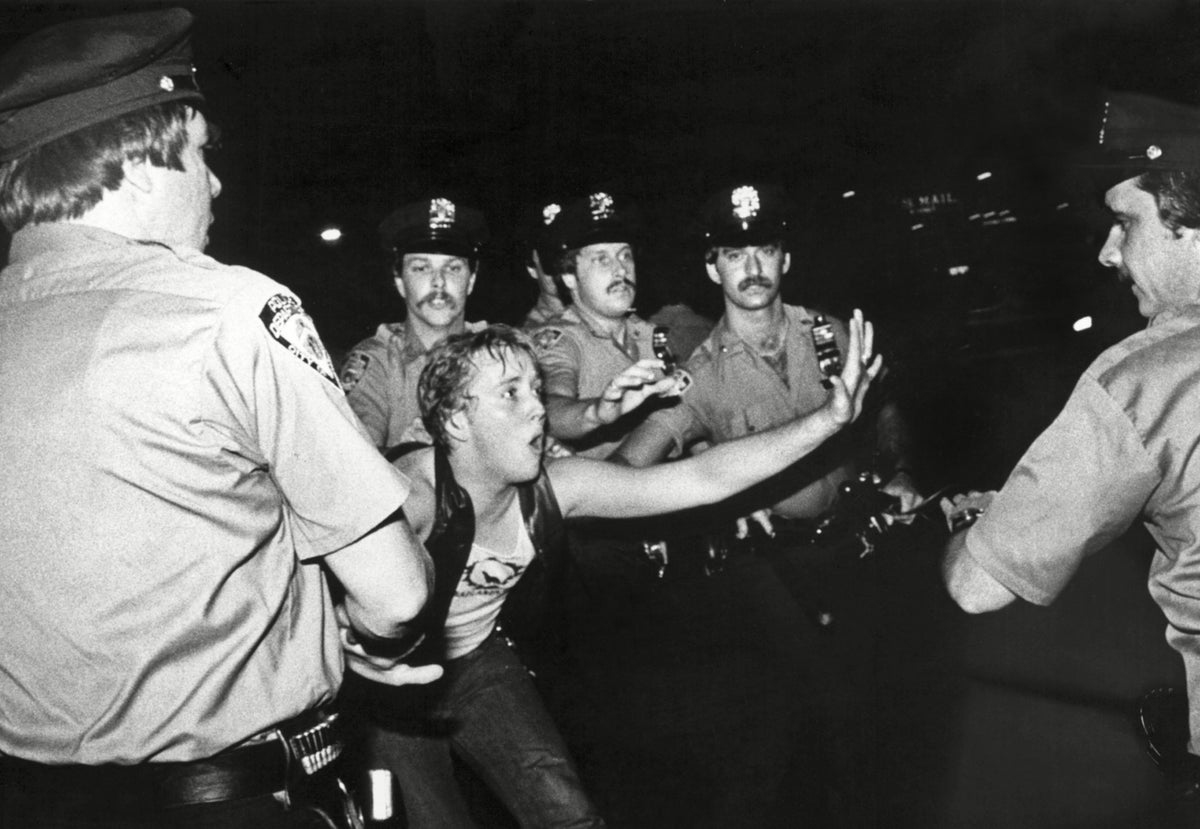

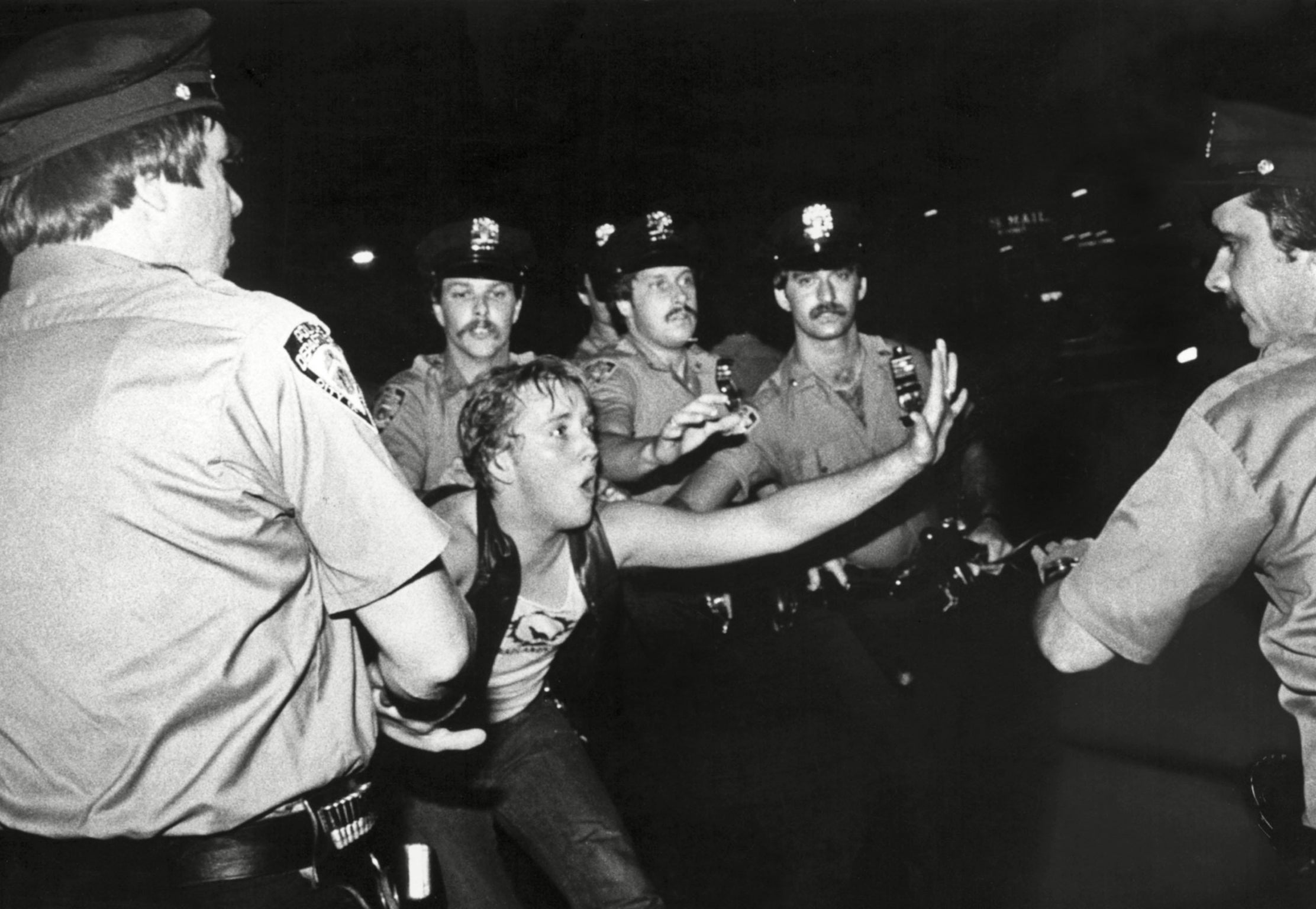

A lengthy delay caused by the authorities having to await the arrival of a wagon to collect the Inn’s seized alcohol stock allowed tensions to fester on Christopher Street, with anger mounting among the growing crowd of bystanders over the officers’ treatment of the bar’s lesbian patrons, some of whom they are said to have molested during searches.

Suspected Mafia members were finally loaded into one wagon and arrested customers into another. Onlookers began to chant “Gay power!” and sing “We Shall Overcome”, booing when an officer shoved a transvestite and cheering when he was hit in the face with a purse in retaliation.

Matters finally came to a head when one woman – later named as Storme DeLarverie - complained about the tight handcuffs placed on her wrists and was beaten with a nightstick, prompting her to fight back against four officers and incite the crowd to come to her aid. The scene erupted.

Activists Marsha P Johnson and Sylvia Rivera - trans women of colour, the former celebrating her 25th birthday that night – were among the first to throw bottles at the police before being joined by others throwing pennies and beer cans. What followed was a 45-minute melee, the crowd taking on the NYPD with rubbish bins, flaming garbage, cobblestones and bricks from a neighbouring construction site.

The cops - along with folk singer Dave Van Ronk and Village Voice writer Howard Smith, who had both been compelled to investigate the chaos - barricaded themselves inside the Stonewall for their own safety, covering the windows with plywood planks, only for the doors to be charged in with a parking meter torn out of the pavement for use as an impromptu battering ram.

As the protesters broke in and the bartop was set on fire with lighter fluid, a Tactical Police Force unit arrived to free their colleagues.

They were greeted by a chorus line, its participants linking arms and kicking their legs in the air like Parisian cancan dancers.

When order was finally restored in the early hours of the morning, the Stonewall Inn had been completely trashed – its washroom, mirrors, jukeboxes and cigarette machines all destroyed. Thirteen people were arrested, four officers treated for injuries and many others hospitalised.

The rioting resumed the following evening and for several nights after, by which point the bar had already become a focal point for anti-police unrest, its walls daubed with graffiti declaring “Drag power!” and “They invaded our rights!”.

Johnson is said to have smashed a patrol car’s windshield by dropping her bag on it from the top of a lamppost as thousands took to the streets of Greenwich Village in defiant mood, rocking cars and rallying against a humiliated NYPD.

Their point had been well and truly made.

As Beat poet Allen Ginsberg put it: “Gay power! Isn’t that great! It’s about time we did something to assert ourselves... You know, the guys there were so beautiful – they’ve lost that wounded look that fags all had 10 years ago.”

In Stonewall’s immediate aftermath, the Gay Liberation Front and the less confrontational, more orderly Gay Activists Alliance were soon formed to organise rights activism while the newspapers Gay, Come Out! and Gay Power entered publication, preaching empowerment.

On the one year anniversary of the riots, marchers coordinated by activist Brenda Howard and others gathered in Manhattan – and at parallel events in Chicago and Los Angeles - to celebrate “Christopher Street Liberation Day”, honouring the Stonewall riots and what had quickly been recognised as a watershed moment in LGBT+ rights. Gay Pride was born, with more and more cities across the world staging their own carnivals and street parades to champion gay, lesbian and trans culture.

It took another 30 years before a US president, Bill Clinton, officially declared June “Gay and Lesbian Pride Month”. Fellow Democrat Barack Obama extended its title to the more inclusive “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Pride Month” in 2009.

The Stonewall riots were both a spontaneous outburst of frustration and anger at the oppression of LGBT+ people and very much a product of their moment.

One of the most turbulent decades in American history, the 1960s had begun with a rush of counter-culture optimism but was spiralling towards disillusionment by its close after the assassinations of John F Kennedy, Bobby Kennedy, Malcolm X and the Reverend Dr Martin Luther King Jr and the ever-more-futile sacrifice of young American life in an unwinnable Vietnam War.

The hippie dream would die with Charles Manson and Altamont and the righteous anger of the Black Panthers seemed like the only means left open for those determined to achieve the goals of the civil rights movement and bring about meaningful social reform.

The Stonewall fightback may have been chaotic but it was also exactly the sort of radical, authentic, provocative eruption the world needed to wake up to the rights and fundamental human dignity of citizens in America and beyond who had suffered in the shadows for far too long.