Pope Francis, the 266th Supreme Pontiff and the first Latin American and first Jesuit to lead the Roman Catholic Church, has died aged 88.

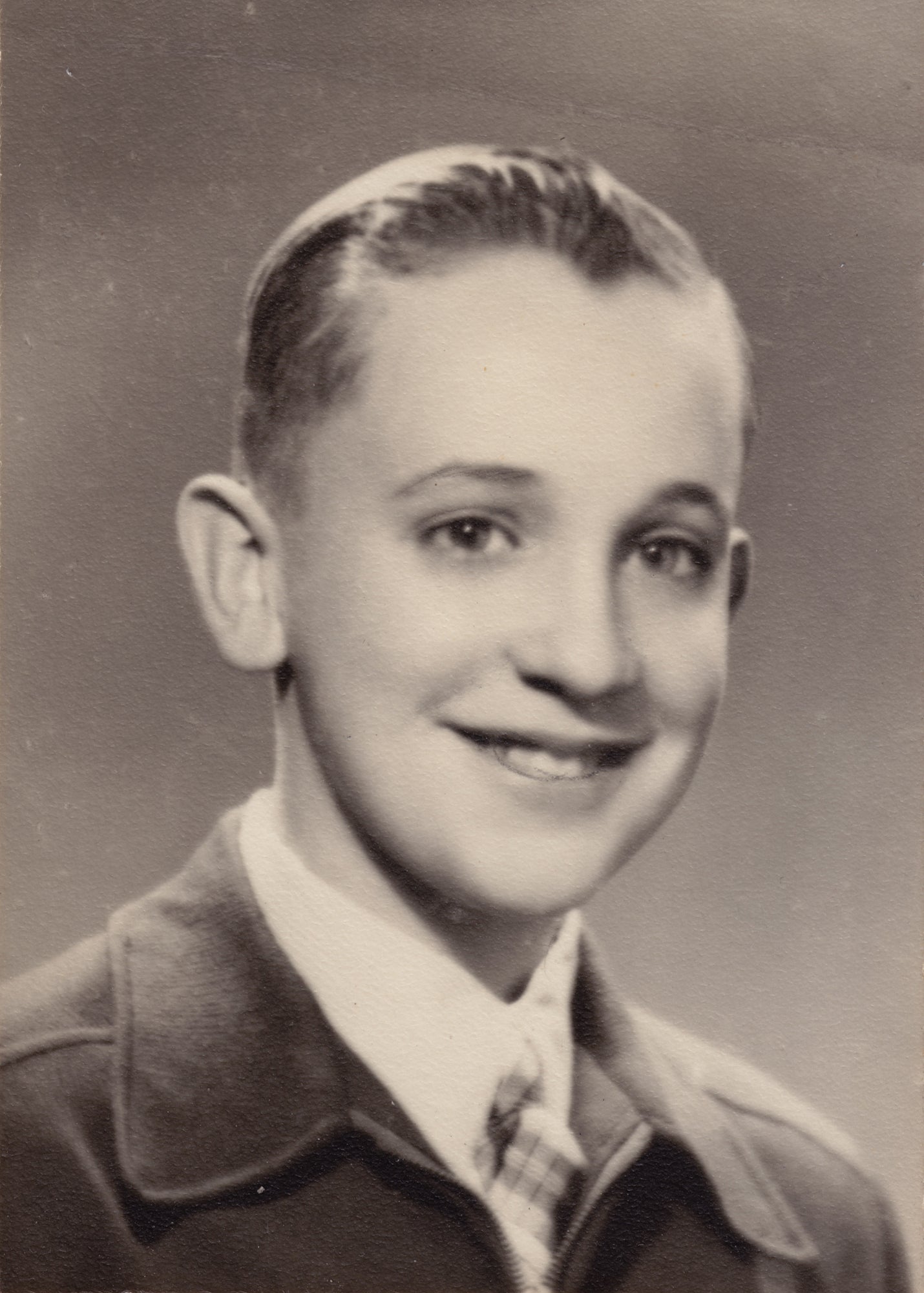

He was born Jorge Mario Bergoglio on 17 December 1936 in the Flores district of Buenos Aires, Argentina, the son of Italian immigrants. His father, Mario, whose family had left their homeland when Benito Mussolini came to power, was an accountant employed by the railways and his mother, Regina Sivori, a housewife devoted to raising the couple’s five children.

As a boy, Jorge Bergoglio attended the Wilfrid Baron de los Santos Angeles school in Ramos Mejia before earning a qualification as a chemical technician from the Escuela Tecnica Industrial 27 Hipolito Yrigoyen, which enabled him to give up his part-time jobs as a bouncer and janitor to work at the Hickethier-Bachmann Laboratory, a food processing plant.

As fond of football, neorealist cinema and tango as any self-respecting Argentine, Bergoglio abandoned his career after being inspired to join the priesthood, instead studying at the archdiocesan seminary at Villa Devoto in his home city. His resolve was tested when he fell in love with a young woman, although ultimately it never wavered. A dangerous bout of pneumonia, contracted when he was 21, might also have curtailed his mission, but his life was saved when surgeons removed a portion of his right lung.

Recovering, Bergoglio entered the Jesuit novitiate of the Society of Jesus on 11 March 1958 before turning to academia, studying humanities in Santiago, Chile, until 1963 when he returned to Buenos Aires to earn a licentiate in philosophy from the Colegio Maximo de San Jose in San Miguel. After graduating, he taught literature and psychology at Santa Fe’s Colegio de la Inmaculada Concepcion from 1964 to 1965 and then at the Colegio del Salvatore in 1966.

Bergoglio returned to San Miguel between 1967 and 1970 to earn a degree in theology, in the midst of which, on 13 December 1969, he was ordained as a Jesuit priest by Archbishop Ramon Jose Castellano. He then continued his training at the University of Alcala de Henares in Spain between 1970 and 1971, before taking his final vows on 22 April 1973.

Just three months later, he was named provincial superior of the Society of Jesus in Argentina, a post he held for six years, his tenure happening to coincide with Jorge Videla’s military coup, which overthrew the country’s leftist president Isabel Peron.

Bergoglio would later be accused of failing to stand up to the junta during the Dirty War years and even of directly collaborating with the dictatorship, particularly over the case of two priests, Orlando Yorio and Franz Jalics, who were kidnapped and tortured in 1976. He always resolutely denied doing so, saying he had actively shielded people from the regime on church property, even claiming to have given his identification papers to one man who physically resembled him so that he could escape across the border.

Bergoglio spent the 1980s serving as a seminary teacher in San Miguel and as rector of the Colegio Maximo de San Jose before departing for Germany in 1986 to pursue his postgraduate studies at the Sankt Georgen Graduate School of Philosophy and Theology in Frankfurt.

On 20 May 1992, he was appointed Auxiliary Bishop of Buenos Aires by Pope John Paul II and Bishop of Auca on 27 June. When Cardinal Antonio Quarracino died six years later, Bergoglio succeeded him as the city’s archbishop and, three years after that, he was made a cardinal.

An increasingly prominent public figure in Argentina in those roles, Bergoglio became known for his efforts to aid the impoverished occupants of the slums of Buenos Aires, preferring to live in a humble downtown apartment himself and travel on foot or by public transport when the country became embroiled in economic crisis at the turn of the century.

“My people are poor and I am one of them,” he once said, continuing to live by that dictum even as Pope, when he gave up the luxury penthouse occupied by his predecessors at the Apostolic Palace and his summer retreat at Castel Gandolfo, preferring to live simply in the Vatican’s Domus Sanctae Marthae (House of Saint Martha) guesthouse instead.

Gone too were the plush red leather “shoes of the fisherman” worn by his predecessors. He kept the same simple black shoes he always used and wore cheap plastic watches, giving some away so they could be auctioned off for charity.

Greater renown brought political complications for the church leader over the next decade, a time of great change for Argentina, in particular when the government of Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner legalised same-sex marriage in 2010 and promoted free contraception and artificial insemination. Bergoglio’s relations with Kirchner were as tense as they had been with her husband and predecessor Nestor Kirchner and would only ease in later years.

With the surprise resignation of Pope Benedict XVI on health grounds, Jorge Mario Bergoglio, by now 76, found himself elected Supreme Pontiff by the papal conclave on 13 March 2013, choosing the name Pope Francis in honour of St Francis of Assisi. He had been a popular choice for the papacy because he was believed to hold relatively orthodox attitudes towards sexual ethics while also being socially progressive, meaning that both traditionalist Catholics and modernisers could be satisfied.

Entering the Vatican, Pope Francis made it his mission to rein in Curia bureaucracy, stamp out financial corruption and address the Church’s shameful history of concealing systemic sexual abuse among the priesthood.

Averse to stuffy formality, the new Pope made for a genial presence on the world stage and endeared himself to a younger generation by maintaining that the Church should apologise to the LGBT+ community for past wrongs rather than sit in judgement, speaking out passionately on the climate crisis as a “moral” concern, against the death penalty and denouncing the inhumane treatment of refugees in Europe, decrying the squalid conditions many asylum seekers endured in over-crowded detention centres.

Under his watch, an overhauled Vatican constitution allowed any baptised lay Catholic, including women, to head most departments in the Catholic Church’s central administration. He put more women in senior Vatican roles than any previous pope – but not as many as progressives wanted.

Mindful of the need to appease the conservatives within his congregation and strike a balance in his public statements, Pope Francis also used his office to speak up for the “traditional” family, reaffirm the Church’s opposition to contraception and declined to endorse the ordination of female priests, despite being broadly supportive of women’s rights within Catholicism.

He led by example when Italy was particularly hard hit by the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, cancelling his regular audiences in St Peter’s Square to prevent the spread of the virus, calling on Catholics to get the vaccine as a matter of personal responsibility and again reminding followers not to forget the less fortunate at a time of international turmoil.

In response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Francis appealed to both sides to find a peaceful resolution to the “spiral of violence and death”, but, for many, he was too cautious in seeking to avoid criticising Vladimir Putin outright. The conflict brought relations between the Vatican and the Russian Orthodox Church to a new low in 2022 when Francis said its head, Patriarch Kirill, who supported the conflict, should not act like “Putin’s altar boy”.

Francis enjoyed considerable prestige internationally, both for his calls for social justice as well as for risky political overtures. He made more than 45 international trips, including the first by any pope to Iraq, United Arab Emirates, Myanmar, North Macedonia, Bahrain and Mongolia.

In 2014, secret contacts mediated by the Vatican resulted in a rapprochement between the long-hostile United States and Cuba.

In 2018, he led the Vatican to a landmark deal on the appointment of bishops in China, which conservatives criticized as a sell-out by the Church to Beijing’s communist government.

In the 2018 interview with Reuters, he said Donald Trump’s decision to pull out of the 2015 Paris climate agreement had pained him “because the future of humanity is at stake”. The Pope and Trump were at odds over many issues, mostly immigration.

Throughout his pontificate, Francis spoke out for the rights of refugees and criticised countries that shunned migrants. He visited the Greek island of Lesbos and brought a dozen refugees to Italy on his plane, and asked Church institutions to work to stop human trafficking and modern slavery.

The longer his reign continued, the more criticism he faced from conservatives, with critics speaking out before the Synod of Bishops in October 2023 to warn that he posed a “risk to the very identity of the Church” by proclaiming it must be “open to all”. Cardinal Raymond Burke, for one, accused him of “bringing forward an agenda that is more political and human than ecclesial and divine” and cautioned that his push to modernise would bring only the “poison of confusion, error and division”.

Pope Francis responded in an address the following day by urging the bishops not to be drawn into “human strategies, political calculations or ideological battles” and stressing that the gathering was not to be treated as “a parliamentary meeting or a plan of reformation”, a characteristically pragmatic answer that underscored the vast complexity of the task before him: namely, leading so ancient an institution into the 21st century.

In February 2025, days after rebuking new US president Donald Trump for his hostile policies targeting illegal immigrants, Pope Francis was taken into care at Rome’s Gemelli Hospital with a respiratory infection that was later confirmed as a “polymicrobial infection”, which doctors said merited a prolonged stay and amounted to a “complex clinical situation”, leaving Catholics around the world to pray for his recovery.

Jorge Mario Bergoglio (Pope Francis), Supreme Pontiff, born 17 December 1936, died 21 April 2025