Perhaps there was such a thing as magic after all: magic in the house, in the equipment, in the runes…

Headley Grange, Hampshire, spring 1974. former Free dummer Simon Kirke walks into the run-down, three‑storey former poorhouse where Led Zeppelin had recorded parts of Led Zep III and IV, where Robert Plant had sat and written the lyrics to Stairway To Heaven inside a single day, and the first thing he claps eyes on is Bonzo’s giant drum kit set up in the entrance hall, plastered in its runic symbols. “Fuck me,” he thinks. “This is great!”

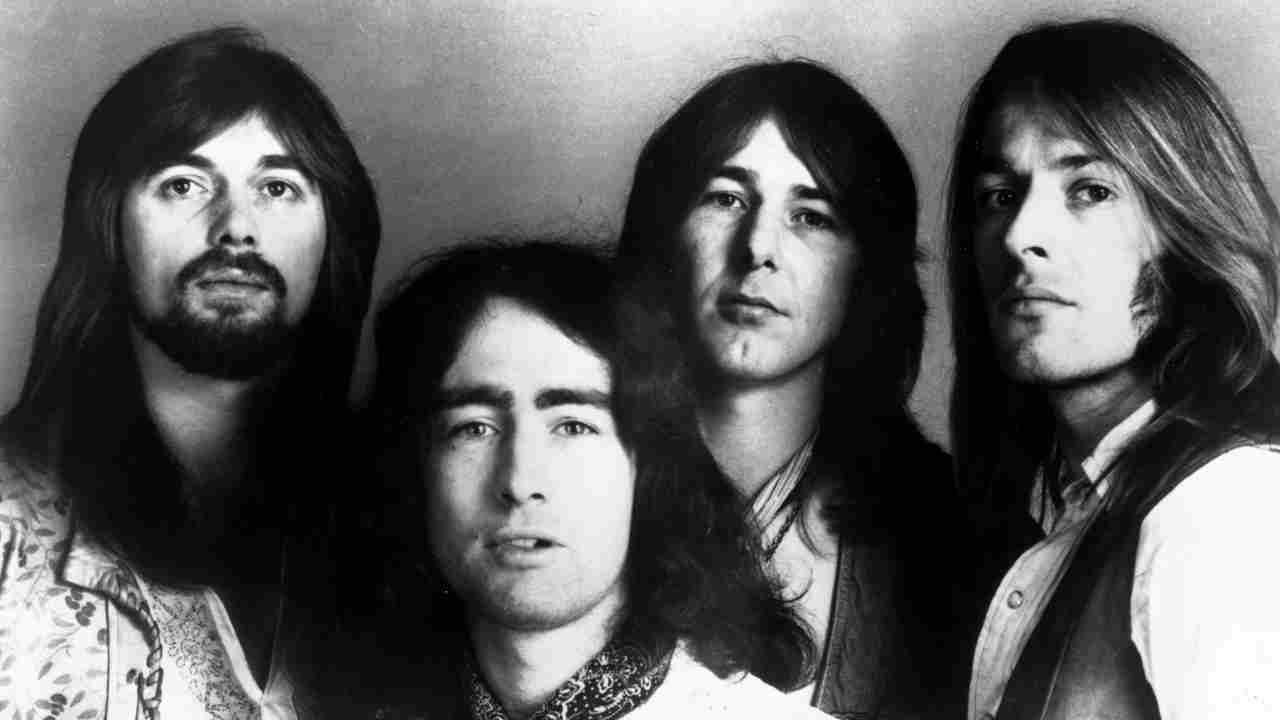

Call it magic, call it luck, call it serendipity, call it what you like, but there was something going on; something smoothing their path, clearing the way. Look at how they got here, after all. Kirke and his pal Paul Rodgers, the ‘country boy’ (read: not from swinging London), half of the late and not-yet-as-lamented-as-they-would-be Free; Mick Ralphs from Mott The Hoople, a man writing songs too good for the singer of his band to sing; and ex-King Crimson bassist Boz Burrell, a fellow who took life as easy as his wide smile. They came together in the kind of semi‑planned, semi-fortuitous way that mitigated against the label of ‘supergroup’ (and its usual connotations of musicianly self-indulgence) that was quickly applied and still sticks.

They were at the Grange because Led Zeppelin were supposed to be there – all of their gear was, and so was Ronnie Lane’s mobile recording truck – but John Paul Jones had come down with the flu and so there were 10 days of expensive studio time lying fallow while Jonesy sorted himself out. And as Bad Company shared a manager with Led Zeppelin, well…

And that was another story, another case of things sliding into place. Peter Grant, the heavyweight ex-wrestler, who was becoming the emblematic rock manager of the age. Part entrepreneur, part gangland overlord, he was the man the bullish Rodgers had been encouraged to phone by Free’s former tour manager, Clive Coulson. Grant had arranged to come and see the new band rehearse at a village hall in Surrey. They’d waited all afternoon for him to turn up, only to discover that Grant, wanting to catch an unmediated earful of what they did, had waited outside to listen to them rehearse. What he heard had convinced him to take them on.

With their material written and ready to go, it wasn’t the big man’s most difficult decision to pick up the phone and offer them the Grange once Jones went down with that bug.

Had Bad Company cut their first album anywhere else, it would still have had the songs and it would still have contained their essence, but the Grange offered something else: a strange sense of place that came in part from its history. It was the scene of a famous riot by its inmates in the 1830s, and something of their anger and despair must have seeped into the walls – and also from the bands that had brought their own peculiar energies to it. Many years later, in 2009, Jimmy Page revisited the Grange for the film It Might Get Loud and admitted to being overwhelmed by the memories and emotions that came rushing back to greet him.

Then there were the odd happenings that come with a building of that age and condition. Rodgers later recalled a picture on one of the staircases, a landscape painting of sheep that somehow transformed into wolves. There were the damp walls and the creaking floorboards and the things that went bump in the night. All of those indefinable elements are somewhere in the record, just as they are in the albums that Led Zeppelin made there, and in the subconscious dreamings of The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway, the record that Genesis would write at Headley Grange just a few weeks after Bad Company had left.

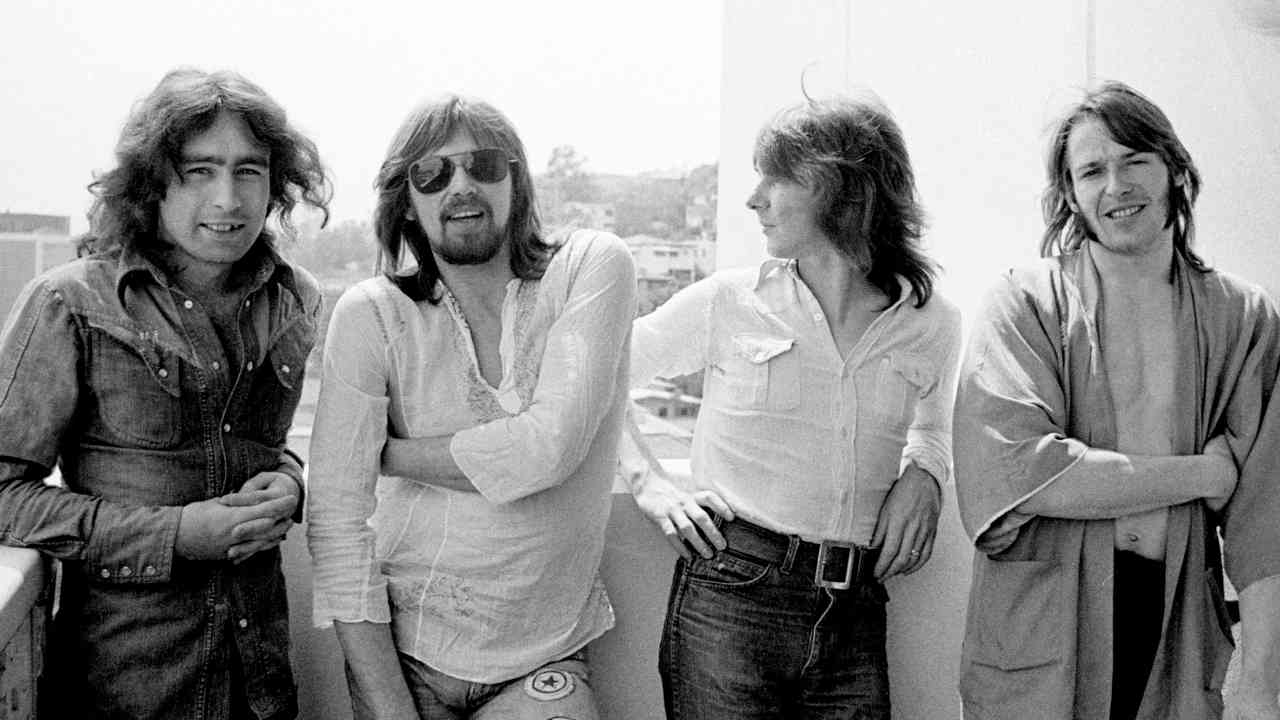

The band weren’t just digging the vibes of the Grange – they were becoming intoxicated by the new chemistry they were creating together. During the Free years, especially towards the end, Rogers and Kirke had been hostage to the addictions and insecurities that were to destroy and then end the life of their guitarist Paul Kossoff. His shimmering brilliance was symptomatically diminished to the point where, before one of their final shows, Kirke was on his knees in the dressing room trying to show Kossoff the chords to All Right Now, a song he had played hundreds, if not thousands of times. Rogers, who was equally as gifted as the guitarist – and arguably more so – now forged a new partnership with Mick Ralphs, an entirely different character to the tortured Koss.

As Simon Kirke told Classic Rock, “You couldn’t have been further away from Paul Kossoff than Mick Ralphs. I wasn’t interested in any more geniuses. Mick drank – of course he drank, he was from Hereford! – but he was great fun. And he brought Rodgers out of his shell. By the end of Free, Paul had his back to the audience; he didn’t want to know. Then Ralphs came along with his Max Wall impressions and the whole thing changed – and for the better. Paul really blossomed with Mick.”

It had been something of a coquettish courtship. Ralphs was still attached to Mott The Hoople when they met during a US tour, and Rodgers had his first post-Free band, Peace, although he was contemplating a solo record. All of that changed, though, once they had disentangled from their other partners. They were a perfect creative partnership, and one that fired right away: the first song that Ralphs showed Rodgers was Can’t Get Enough. The guitarist might have dismissed it, with some misplaced modesty, as “a three-chord bash”, but it was exactly the kind of song that Rodgers’ unsurpassable voice could fully inhabit. Kirke retained his effortless swing behind the kit and Boz Burrell proved that his playing was as easy-going as he was.

Deep within its grooves was the essence of the band to come. While Mott went off on a journey into 70s glam, Ralphs had found his home. He played Rodgers Ready For Love, another of the tunes he’d written – and actually recorded in this case – with Mott The Hoople. Once again, when the other Bad Company ingredients were mixed in, it emerged as a solid-gold staple of the classic rock sound; one of the pillars on which the genre would be built.

Rodgers had rediscovered the instincts that were beginning to desert him as Free fractured. “I found out they [Mott] had already recorded Ready For Love,” he told Mick Wall, “and I thought, ‘Oh, I don’t care…’ It was such a good song and a good vehicle for my voice. A great composition. One of Mick’s finest, actually; possibly his best.”

In Rodgers’ effortless voice, Ralphs’ songs had their ideal interpreter. There’s a yearning in the way he sings them that carries across the decades, a sweet sadness that gives the songs the common touch.

Can’t Get Enough was the first tune the band laid down, and it became a blueprint that would last throughout their career – at least the parts when Rodgers was fronting them. It’s hard to find any moment when he over-sings – his judgement and musicality are immaculate, and the band stay out of his way. The kind of showboating that blighted some of the bloated rock giants who would perish a few years later when punk arrived was entirely absent with Bad Company. What strikes the listener even now is how straightforward they are. It’s probably why the songs still sound so good on the radio stations of America that play them to this day.

Any record with those two songs on would have launched a band, but Bad Company had begun recording at the optimum moment. They had more material ready to go, and they were tight, rehearsed, seasoned. They didn’t need a producer – they weren’t Pink Floyd, after all – and they were experienced enough to know which parts of the songs needed nailing to the floor and which could kick back and allow a little of the Grange in.

Seagull, the simple and beautiful acoustic tune that would close the record, had come together when Rodgers’ lyric and melody were joined by Ralphs’ chorus arrangement. The song was completed with Rodgers sitting outside in part of the Headley Grange gardens at night, a vibe that chimed perfectly with the atmosphere of the tune. It was a trick the singer repeated on the album’s title song, the epic Bad Company, although he channelled other aspects of the night into that one.

The themes of the band ran through the song too. They had battled to keep the name when various marketers had suggested it was too negative for so freewheeling a group, but Rodgers was set on the imagery. He’d picked it up from a recently released Robert Benton Western called Bad Company, in which Jeff Bridges and Barry Brown played a couple of draft dodgers from the American Civil War in an obvious allegory for Vietnam, which was the lightning-rod conflict of the era. The three chords that introduce the song are also in the movie’s soundtrack. Rodgers won the fight and the song opened side two of the record. It’s odd to think now that it might not have been there.

“Too much clutter makes a record sound small,” Mick Ralphs would say many years later, and the rest of Bad Company lives by that credo. Rock Steady, Movin’ On, Don’t Let Me Down – all songs that could be played by any covers band worth their salt, and yet what sets them apart is the chemistry of their originators.

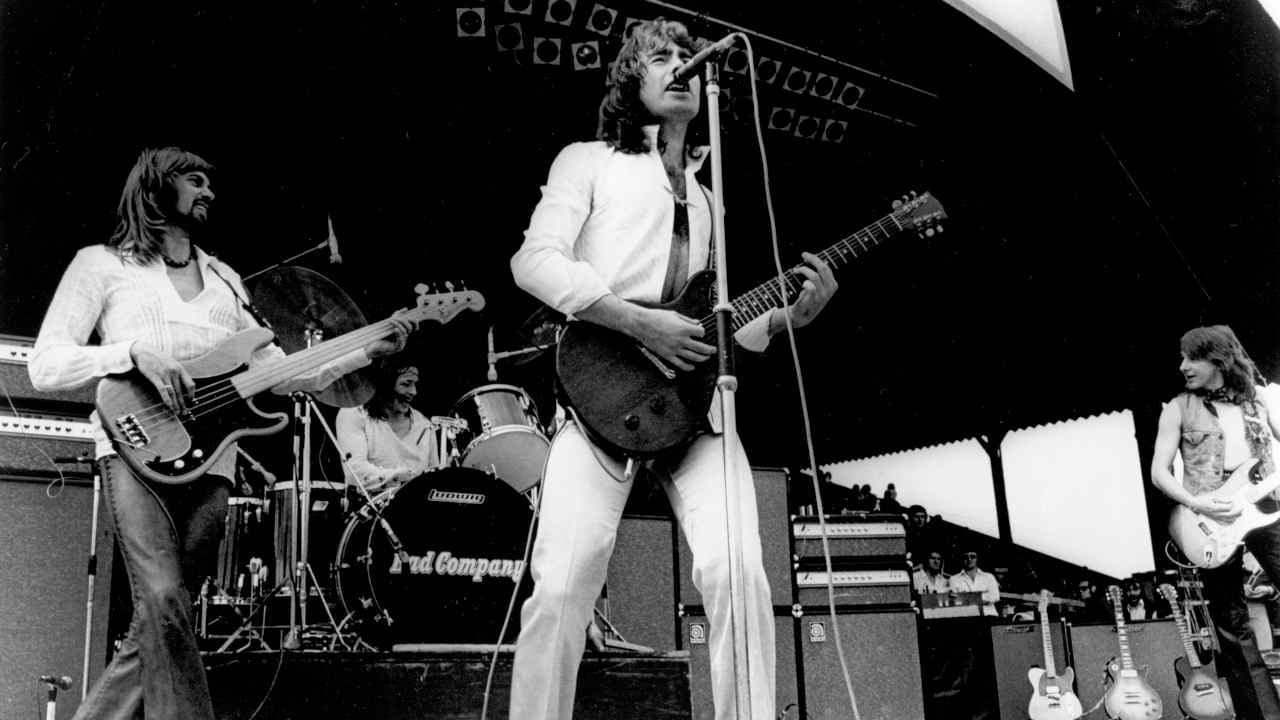

After 10 days of work at the Grange, they had a record. They also had a lot to live up to. Peter Grant had told them to worry about the music and he would take care of the rest. Eschewing the ‘no singles’ policy that was forging the Zeppelin legend, he led them out with Can’t Get Enough, a song that rocketed to the top of the US charts and made the album one of the most anticipated of 1974.

When it came, it was dressed in an austere black-and-white sleeve, the band’s name (abbreviated to just Bad Co.) running from the bottom left-hand corner to the right-hand top. It contrasted with the excess of the decade that surrounded it, where everyone from Zeppelin and The Who to Pink Floyd, Genesis and Bowie were gelling music, image and artwork into an aesthetic whole. Instead, Bad Company made the simplest of statements, one that pointed the way for the likes of AC/DC’s Back In Black and Metallica’s Black Album (and, yes, Spinal Tap’s Smell The Glove, a joke that Bad Company in a way set up).

As a suggestion of the band’s music, it was perfect, and when the record came out, an audience was waiting. It was Top Five in the UK right away, and within a couple of months it topped the US charts. Grant, with typical showmanship, kept the information from the band until they were just about to step on stage in Boston for the final show of their first American tour, when he led them into an anteroom and pulled back a sheet concealing four gold albums, one for each member of the band.

“He had tears in his eyes,” said Simon Kirke, “and so did we. He gave a lovely little speech and then he said, ‘Now get the fuck out of here and knock them dead…’”

It was a deserved triumph for them all: the four members of the band had emerged from the shadows of their past, and Grant had proved that he was more than a one-act wonder. Eight songs, tight and chilled, and with some magic inside them somewhere, were enough to clear the decks and give them all a fresh start.