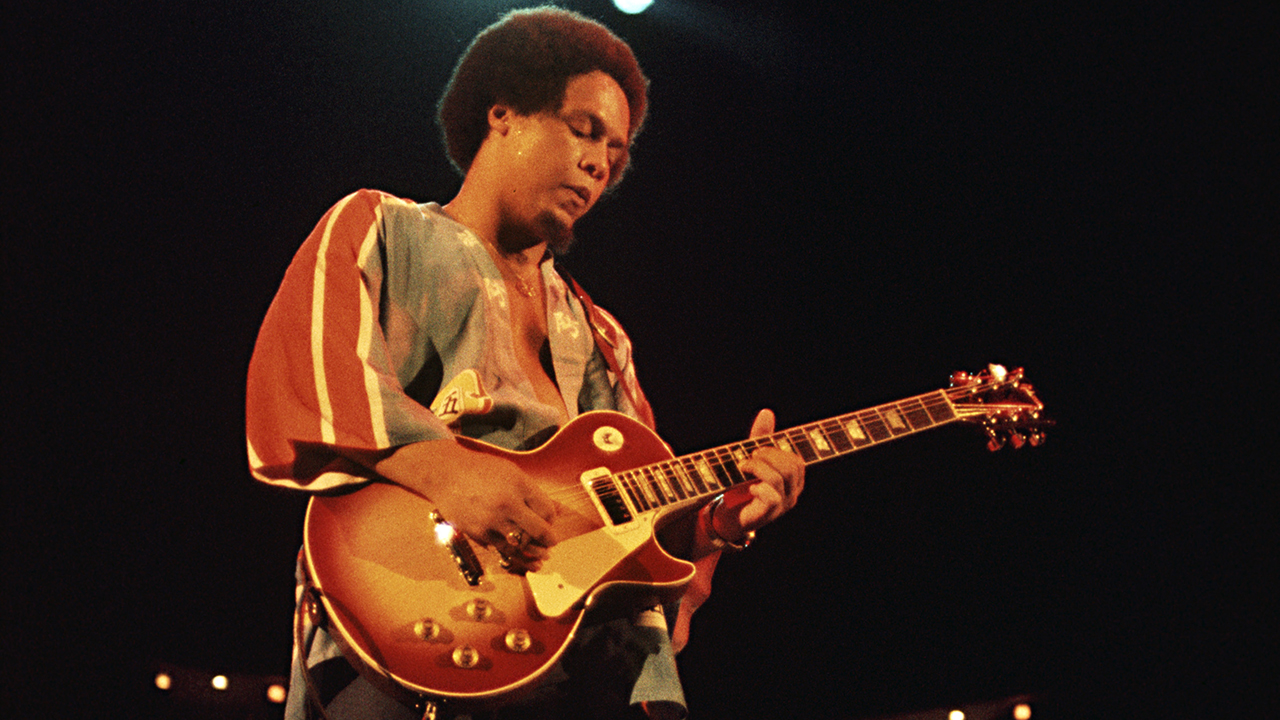

Caleb Quaye left the music business in the ‘80s, after a career spent inheriting assignments slated for Jimmy Page and palling around with Pete Townshend and Elton John. “But I kept playing,” he tells Guitar World, “in a Christian band for my church and at evangelistic events.”

In the ‘70s Quaye was an ace whose licks enhanced tracks ranging from Harry Nilsson’s Coconut to Elton John’s Tiny Dancer. He was a full-time member of John’s band and also lent his talents to Lou Reed, Hall & Oates, Mick Jagger, Paul McCartney, The Beach Boys, Peter Criss.

It’s his days with Elton John that mean the most. “I was easy in the studio,” he recalls. “Elton might say, ‘I want it to sound like this.’ We all knew what ‘this’ meant – we could creatively turn on a dime.

“We understood his influences. Elton and I spent a lot of time in those early days listening to music, playing and spending all our money at record stores buying all kinds of import albums.”

Despite being out of the business for over 40 years, Quaye’s legacy looms large. One can’t help but wonder what it might have looked like if he’d stuck around – but he has no regrets.

“I’m proud of my contribution to music history. The whole journey in life has been grea,” he says..

“I’ve come to see that it was orchestrated by God. There’s a delusion in the industry, where people become successful and think it's all them. Real freedom comes when you discover it’s not all about you.

“It’s a blessing to bless others with music. I get emails that say, ‘Your work and playing meant a lot.’ It gives me peace. It’s wonderful to have been able to do that.”

What got you into studio work?

“A friend of mine, Billy Nicholls, was signed to Andrew Oldham’s Immediate label. Billy would come in with demos and I would engineer for them. When Billy recorded his first album at Olympic Studios, he wanted me to play on it because I’d helped with his demos.

“Back then everything was union musicians; there was a contractor in the studio, David Katz, and his brother, Charlie. Charlie would be the booker for the strings, and David would book the rhythm section.

“I was there on a rhythm section date; I was maybe 16. After we finished, David said, ‘Caleb, I like what you’re doing. I’ve got all this work lined up for Jimmy Page, but he doesn’t want to do it anymore.’ Jimmy was a top studio guy, but he’d had a meltdown, got fed up and joined the Yardbirds.

“David said, ‘Would you like to do it?’ I said, ‘Yes, sir – I would love to.’ He said, ‘First, I need you to join the Musicians’ Union.’ I ran down the street to the MU office and signed on. All the work lined up for Jimmy Page went to me.”

Was it challenging to measure up to Jimmy’s sound and style?

“I was free to do it as I would do it. Nobody ever said, ‘We need you to play like Jimmy.’ Like most sessions, if there was something specific in the arrangement I’d play it. But outside of that, I was free to do it as I wanted.”

One of your early credits is with Lou Reed on his debut record, featuring Steve Howe. What was that like?

“The recording was spread out over a few days. They used different guitar players, but Steve and I weren't in the same room at the same time. This would have been ’72; I remember using my ’64 Fender Strat going through my Fender Deluxe.”

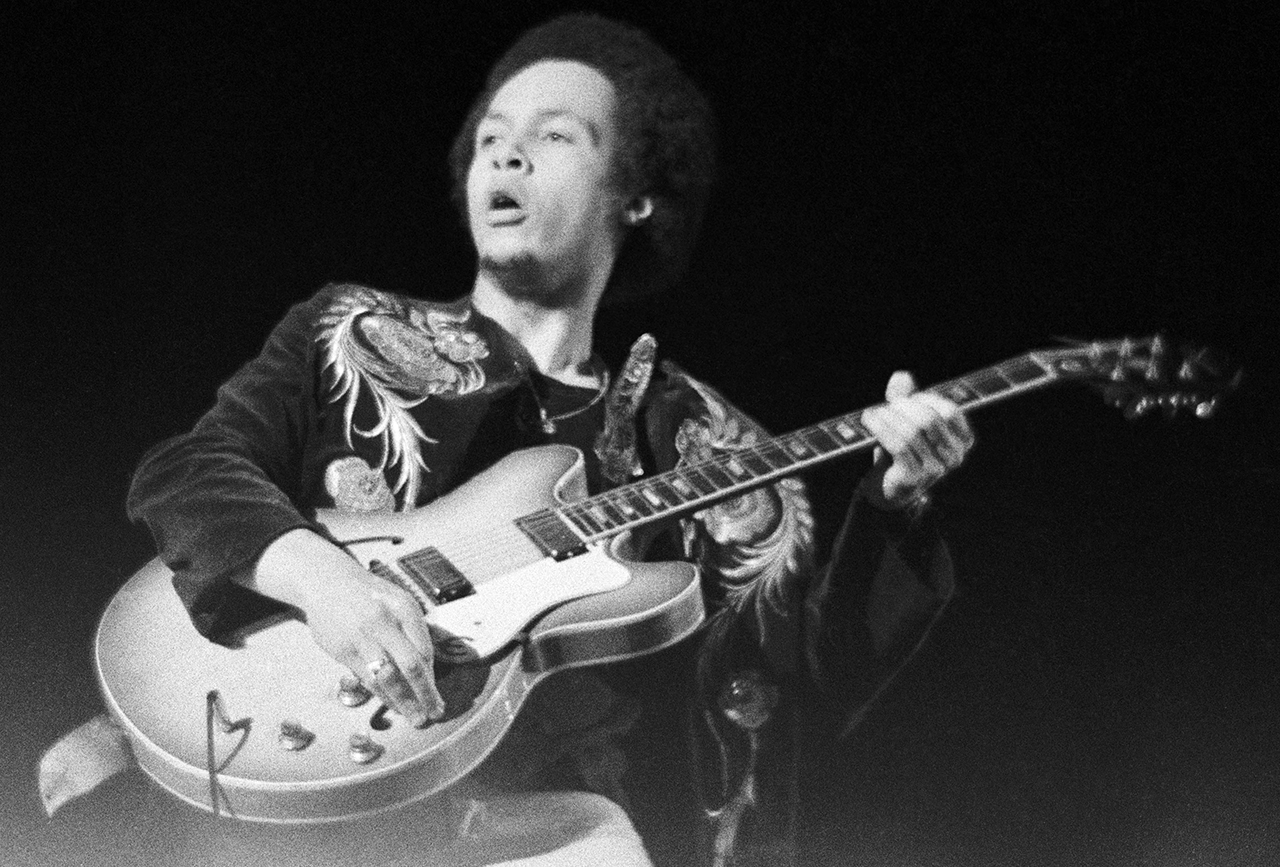

Around the same time you worked closely with Pete Townshend on a song called Forever’s No Time at All, where you played bass, drums and guitar.

“That was great fun. I remember it well to this day – it was with Billy Nicholls, who wrote the song. We cut the track with Billy on acoustic and doing a guide vocal. Then I played drums and added bass and electric. I used my Fender Strat going through the Fender Deluxe.

That tune is made up of one chord… it took 16 hours to record!

“The bass was one of Pete’s; it might have been a Gibson EB-0. He had it hanging on the wall in the studio. Pete engineered the session, and he was having a field day! He loved engineering and he was like a scientist. We had a great time.”

Did Pete give much guidance?

“He just let me do what I do. There was an interview with Pete back in those days that's recently been unearthed. He talked about the session and graciously said he thought I was a genius!”

Why do you think Pete liked your playing so much?

“It was the jazz influence. I remember taking a tea break; we went upstairs into the kitchen area, and there was a guitar up there. I was noodling around, and Pete was standing watching me. He said, ‘Wow – I wish I could play like you.’ I was thinking, ‘I wish I could come up with the three chords you take to the bank!’”

One of your most memorable credits is Coconut from Harry Nilsson’s Nilsson Schmilsson. How did you end up in that session?

“It was just crazy. That was me with Nilsson and Richard Perry. Unfortunately, they were out of their minds on cocaine and LSD. That tune is made up of one chord – C7. I was playing my trusty Gibson J-45, and they kept stopping and starting.

“It got really frustrating – it took 16 hours to record! Finally, they got what they needed, with a whole bunch of editing. That was not one of my highlights.

“But when the album came out, Rolling Stone and the Melody Maker said, ‘Oh, this is a work of genius!’ I’m reading these reviews, going, ‘No – you guys need to talk to me!’ It was absolutely unbelievable.”

What did your rig look like when you recorded Madman Across the Water with Elton John?

“That was still my Strat. I would have used that on Tiny Dancer, Levon and those songs. Those recordings were a lot of fun to do.”

How did you and Davey Johnstone divide up the guitar-related labor?

“A big factor was that we were friends in those days. There was relational chemistry, because we all grew up listening to the same music – the British Invasion and the stuff from the West Coast like the Beach Boys. We’d have listening parties and soak up all that music from Motown to Memphis.”

Elton had a bit of a meltdown. He put the brakes on everything and needed a rest

You were with Elton from the start. Did you think he would eventually blow up?

“No, we didn’t. We knew we were doing something that was quality; knew it was different, and that we could be on to something. Early on, the word went out, ‘You need to get down to the studio and hear what they’re doing with this guy, Elton John.’

“Different musicians would stop by and listen and say, ‘This is great!’ It was a process – and it eventually came to fruition.”

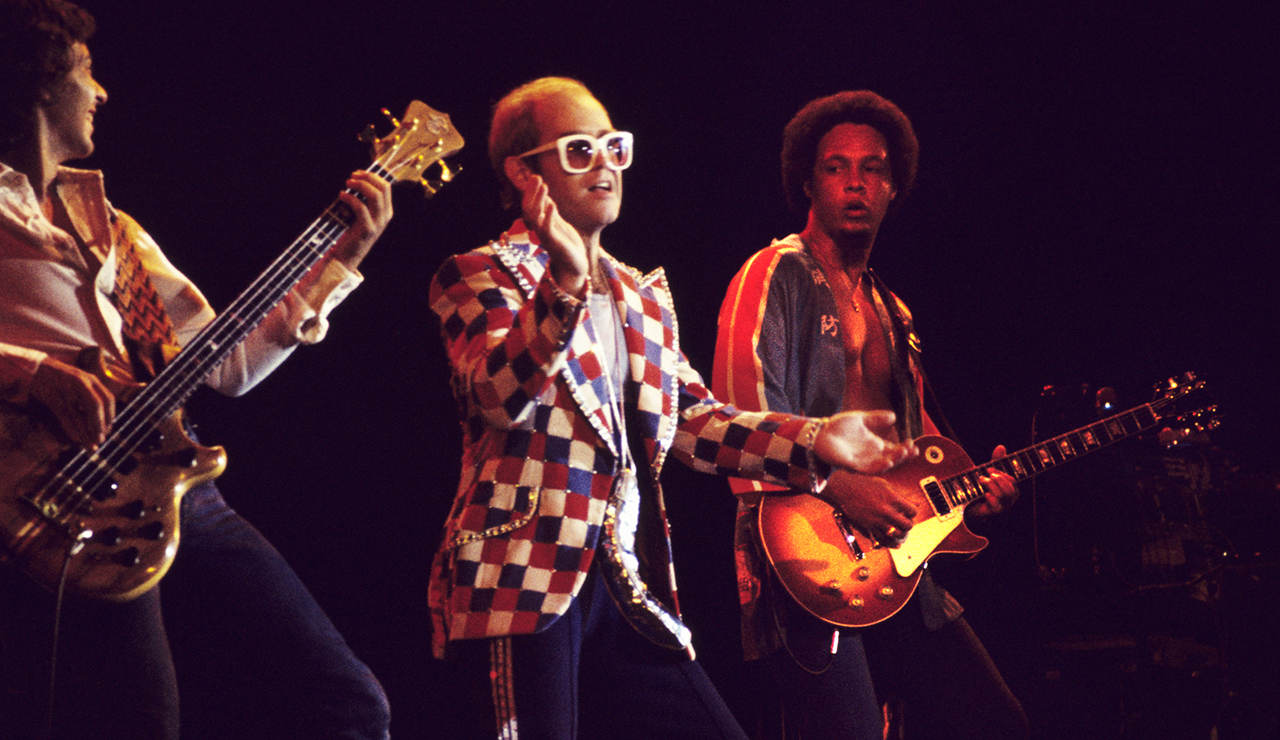

Why did you and most of Elton’s band leave at the height of his fame to work with Hall & Oates?

“Elton was huge by then; he was dealing with his own issues and had a bit of a meltdown. He put the brakes on everything and needed a rest. We were doing a lot of touring, all stadium stuff. He put the brakes on just before the last concert at Madison Square Garden.

“Kenny Passarelli had gotten to know Hall & Oates, who had come to see us, probably at Madison Square Garden. Kenny pitched it to us that they’d like to work with Elton’s very tight rhythm section. So, Roger Pope, Kenny and I auditioned for their new band, and that’s how it happened.”

That led to you working with Robert Fripp on Daryl Hall’s debut solo record, Sacred Songs, in 1980.

“Our styles were so totally different, so polar opposite, that it actually worked! Robert used to say to me, ‘I can’t play blues.’ I’d play blues left and right and he’d say, ‘I can’t do that; I just do this.’ Robert has incredible technique, but he’s not a pocket player. He doesn’t come from that, the blues thing – he has a more scientific approach.”

Were you still using your Strat and Fender Deluxe?

“It was my Epiphone Riviera and a Mesa Boogie Mark I by then. The Epiphone was a cool guitar to play, with great action. I developed a fascination with humbucking pickups, and that guitar was fatter on the lower end.”

Why did you switch to Mesa Boogie?

“You could get sounds dialed in nicely. I had the second batch of Mesa Boogies ever made – the first batch went to Carlos Santana. I got mine while I was on tour with Elton in 1975, and I took them with me when I joined Hall & Oates.”

One of your final credits came on Peter Criss’s third solo record, Let Me Rock You. How was that?

“I’d say there was a certain fun aspect to it. I knew the guys playing on it, and the producer, Vini Poncia, knew a friend of mine. That’s how I ended up on the record. I was never a Kiss fan; it was just another session. But it was fun to do and went smoothly.

Peter Criss was okay… he didn’t come in with any big rock star attitude

“Peter was okay. I wouldn’t consider him a really great drummer, like some of the guys that I know. He’d already left Kiss and was going through a transition, so he was pretty mellow. He didn’t come in with any big rock star attitude. I didn’t even recognize him because Kiss was always painted up on stage!”

Why did you leave the music business in the mid 80s?

“It’s very simple: I became a Christian.”

The two things couldn’t coexist?

“Not the way things were. Through becoming a Christian, I got set free from drugs and everything. It’s a whole different worldview and mindset. It gave me the peace I was looking for. It sorted out the personal baggage I’d carried since childhood. The greatest thing I’ve ever done is say ‘yes’ to Jesus.”