Each time the Jesus Lizard make their way back to the stage, it’s cause for celebration. Even so, when the hard-bruising rock quartet dropped into Nashville’s Blue Room venue within the Third Man Records building this past June, the excitement was markedly different.

Just the day before, the group – who have been maintaining an off-and-on reunion phase since 2008 – officially announced Rack, their first full-length release since the late ’90s. The show likewise featured the live debut of Hide & Seek, the record’s manically concussive lead-off track, which easily proves that the Jesus Lizard’s confrontational spirit remains intact nearly 40 years after the project first got off the ground.

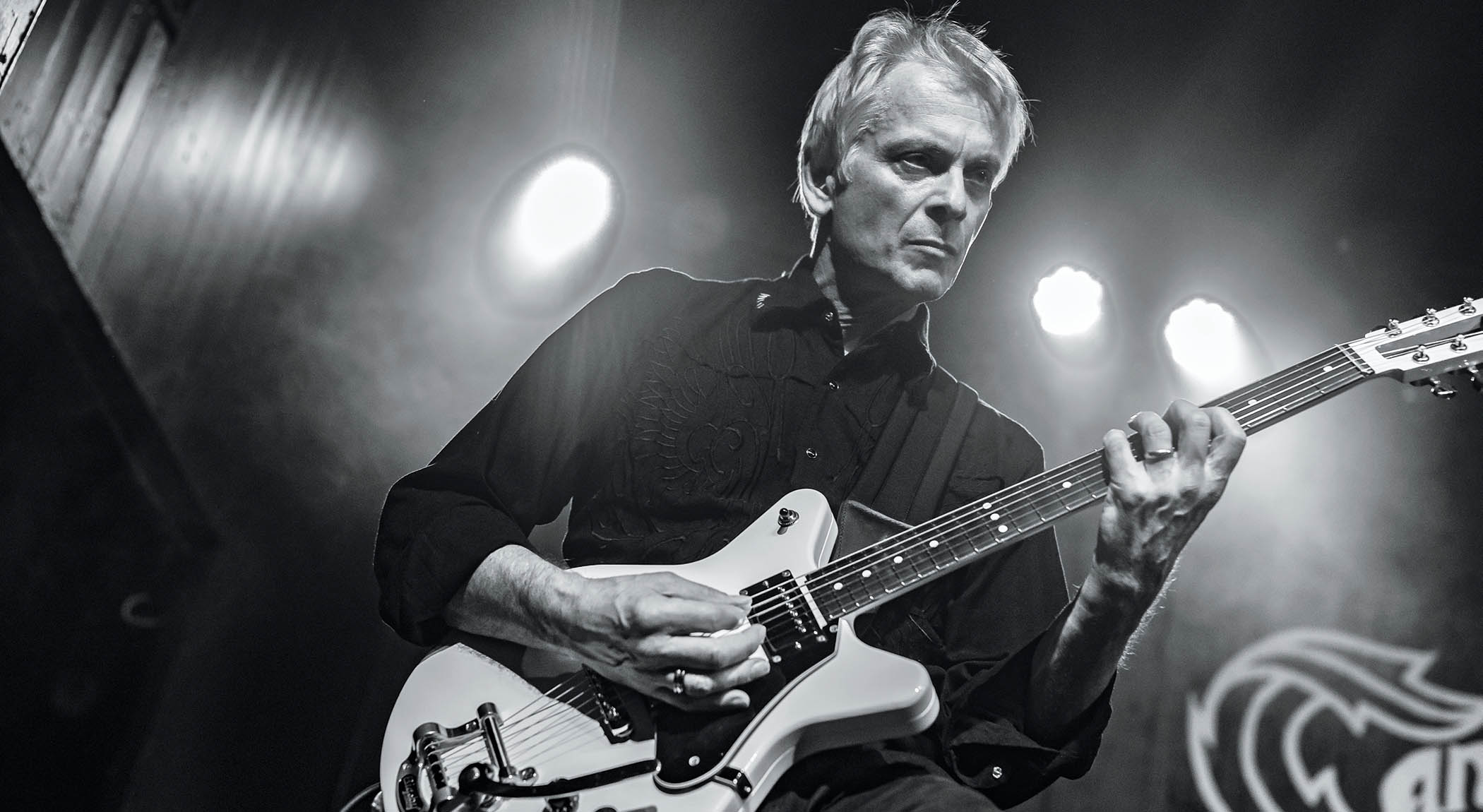

And sure enough, guitarist Duane Denison confirms that sweat-slicked vocalist David Yow was once again surfing his way above their fans, his steel-toe-pointed cowboy boots kicking dangerously against the wind. Something has changed since that first era, though: Yow’s mostly fully clothed now.

“I think he starts off with a shirt these days – he’s not full Iggy – but the boots are still there. He still goes out in the crowd, maybe not quite as much; we worry about that,” Denison says from his Nashville home, alluding to the fact that all four members have now crossed well into their 60s.

“But David Sims is playing his bass; to my left I’ve got Mac [McNeilly] playing drums. Everything’s dialed in, and away we go! The Jesus Lizard takes on a life of its own; I’m a cog in the machine here, but it’s good.”

Denison has been keeping himself well-oiled this whole time. Since Jesus Lizard’s initial dissolution, he’s made five albums of fractiously experimental alt-metal as part of Tomahawk, alongside Mr. Bungle’s Mike Patton; he’s also backed country outlaw Hank Williams III and cut a loose-cannon solo on Morning, Noon and Night from Jack White’s Fear of the Dawn album in 2022. Denison nevertheless admits there was something extra special about getting the Jesus Lizard back in the studio.

Formed in Austin in 1988 by Denison, Sims and Yow, the Jesus Lizard initially delivered art-damaged post-punk subversion with the help of a drum machine.

By the time they moved to Chicago just ahead of the Nineties, they picked up jackhammer percussionist in McNeilly, and together they produced a mean-streaked, unbeatable four-album run with producer Steve Albini, from 1990’s Head through to 1994’s Down.

While heroes within the noise-driven American underground, they also put out a split 7-inch with Nirvana when the latter were at peak-grunge popularity; toured on the mainstage of Lollapalooza in 1995; and by 1996, they’d signed to Capitol Records to deliver Shot.

But then McNeilly left the band before they made 1998’s Blue – which featured drummer Jim Kimball – and while the record teeters toward the bone-grinding intensity of their early work, outliers like the electronica-touched Needles for Teeth seem a little weird to the band, in retrospect.

Conceptualized around 2019 and tracked in late 2023, Rack isn’t exactly a back-to-basics affair for the Jesus Lizard, but Denison’s playing does hold common ground with the decadently slurred jazz licking of Goat’s iconic opening Then Comes Dudley or blues-staggered punch-ups like Puss off of 1992’s Liar. He’s a jazz-trained player who grew up loving prog but was drawn in by the stately post-punk inkiness of Siouxsie and the Banshees and Killing Joke.

Rack reflects all of that and more, whether Denison’s riding a coal-black phosphorescent surf (Dunning Kruger); expressing wide-interval wonkiness (Hide & Seek); or plinking through a newly semi-acoustic kind of creepiness (Swan the Dog).

The album finds the rest of the group in fine, brute form, too. Sims aggressively leans into a series of mid-twonked walking bass freakouts, while his low-end solo on the roadhouse-leveling Lord Godiva is fit with just enough teeth-baring fuzz to show you he means business. Frontman Yow retains his recognizably drawled-and-scratchy, melody-damaged menace. McNeilly’s max-punishment beating is straight but savage.

Indeed, the latest return of the Jesus Lizard – this time in album form – is welcome news to many. To put it as Yow does above the slow-lurching doom-blues of Rack’s Armistice Day, “now the pain is returning.” And damn… does it ever feel good.

There are naturally some similarities between your playing in Tomahawk and the Jesus Lizard. Is there a different kind of consideration you put into the riffs when you’re writing for a vocalist like David Yow, versus someone like Mike Patton?

With the Jesus Lizard, we still do things with odd time signatures, but it’s a bit more stripped down and aggressive

“A little bit. Tomahawk, to me, is a bit more technical and metal, maybe. And Mike, you know, his vocal range and ability to hit intervals is astounding. With the Jesus Lizard, we still do things with odd time signatures, but it’s a bit more stripped down and aggressive. I’m not necessarily looking for melody with the vocals, though sometimes they hint at it.”

Was it all daunting to think about adding to the canon? It has been more than 25 years since the Jesus Lizard released Blue.

“Definitely, especially since that stuff has been kept alive over the years through the internet and through people talking about it. Back in the day, there weren’t chat groups devoted to the band. So, yeah, we’re somewhat aware of not spoiling the legacy.

“But frankly, we felt pretty confident in the material from the start. I don’t think any of us were worried about how it stood up against the other stuff. If anything, there’s a couple of things that actually almost refer to the ’90s-period Jesus Lizard. That’s the point of departure, but we push it into a more modern era from there.”

Are there explicit musical references to your older songs on Rack, or was it more that you were matching the vibe?

“Both. For instance, we’ve been working on different versions of Lord Godiva since the ’90s. We’d actually played that live before, though maybe not in this exact version. But it’s always been a fairly unhinged kind of song.

“David Yow doesn’t remember it, but we also did a rough demo of Falling Down back then that we’ve since revised; it came alive again [during the Rack sessions]. And Alexis Feels Sick references some of the things we’ve done in the past: the drums; the bassline; the way the guitar surfs along on top of it with these single-note, but spread positions.

“It hints at the past, but in an updated package – I don’t mean using all the latest bells and whistles, I just mean representing where we are now.”

That perverted bossa nova in the front end of Alexis Feels Sick has the same feel as something like Low Rider, an instrumental track in the middle of Down.

“I know what you’re talking about. We’ve used that rimshot beat before; there’s a song called Glamorous [off 1993’s Lash EP] that had that kind of feel, too. It’s just a great way to set up tension – that simple, stripped down, sparse feel gives you a lot of room to build dynamics.”

How do you remember the Jesus Lizard drawing down at the end of the ’90s?

“There were basically two periods in the ’90s – there was the early period on Touch and Go Records, and then the period when we signed to Capitol and put out two albums. The second half started off well, but we didn’t end on a high note.

“By that time, the music scene had changed, especially in Chicago. Big, loud, abrasive bands were not necessarily what people were hearing. It was instrumental bands like Tortoise; avant-garde things like Jim O’Rourke and Ken Vandermark.”

“In the bigger scene, Britpop was in; techno was in; hip-hop was in. Everything except guitar-driven hard-rock bands. That last album, Blue, was produced by [Gang of Four guitarist] Andy Gill; we were encouraged by the label to ‘modernize,’ so there are samples on that record and touches of drum machines here and there. And… no-one cared!

“Even diehard fans have never heard that record. It’s probably out of print, and Capitol are not going to do anything with it, because it didn’t sell that much. I was glad to see that chapter close. We all went about our business and dispersed from Chicago. One guy went to New York; I went to Nashville; another guy went to L.A.; one guy stayed in Chicago.

“But when we started playing the reunion shows in 2009, it was liberating. It was gratifying that people wanted to hear those old songs, and wanted to see us play – and that we could still deliver!

“It took a while to get us all on the same page to do this album, but I’m hoping that the reaction will be like when we came back and started playing shows, where people go, ‘Wow, I’d figured you’d be good, but not that good.’”

Hide & Seek tees off this phase as the first single and opening track on Rack. The sound of those two dissonant-run lead breaks feels different within your repertoire.

When I was a teenager, it was the ’70s, and so prog rock was king. I’m not ashamed to admit that I loved it

“When those instrumental passages come in, I’m playing off an interval. It’s a major 7th, but it’s the 5 and the b5 of the key we’re in. Then I throw in some other sevenths in there as well. I wanted to have wider intervals in there, spread them out and then throw in a couple little linear things.

“It had a nice, jarring quality, and the guys all seemed to like it. But I’ve actually been doing that kind of thing all along. I took the solo on one song from Jack White’s Fear of the Dawn album, and I’m kind of doing a similar thing there. And if you listen to Grind, the third song on Rack, I’m also referencing that sevenths-kind of wider interval placement. It’s something that’s worked its way [into my technique] over the years and stayed there.

It’s not that effects haven’t been used on Jesus Lizard records, but there’s an octaver-sounding effect on Hide & Seek that seems a bit more prominent.

“I like to think it’s fairly subtle, but throughout this album I used the Line 6 Helix for a lot of sounds that I put in there. And on What If? I used the Third Man version of the Mantic Flex to get a great crazy, modulated, overdriven sound.”

Since you mentioned the idea of sounding “jarring” – the Jesus Lizard have accumulated this reputation as being progenitors of “noise rock,” but that doesn’t necessarily hit the whole of your sound. The groove of a song like Rack’s Lady Godiva – which is explored on those earlier records, too – almost makes you sound more like a really fucked-up roadhouse blues band.

“Oh, that’s funny. But I never liked the noise rock tag. Obviously it’s kind of noisy, and it’s rock, but those arrangements are fairly involved, as far as the way we [set up] the dynamics.

“To me, a lot of the noise rock thing seemed fairly haphazard, relentlessly shrill and chaotic; there are almost no elements of traditional music. But in our music, there’s verses; there’s the occasional chorus; intros, outros, and breaks. But roadhouse blues? I don’t know… if you say so. [Laughs]”

What kind of music influenced your playing growing up?

“When I was a teenager, it was the ’70s, and so prog rock was king. I’m not ashamed to admit that I loved it. Punk rock hadn’t come along yet. The shredders of my day were Robert Fripp, Jan Akkerman and Steve Howe, who I met when I was 17. We tried to sell him a guitar when Yes came through Detroit.”

What did you try to sell him?

“A friend of mine worked at a guitar shop that carried rare archtop jazz guitars, and there was a Guild George Barnes acoustic-electric. This friend was really pushy and talked to a roadie, and they said to come back the next day to meet at Steve Howe’s hotel room in downtown Detroit. He tried it out and played some stuff on it, but he didn’t buy it.”

You’ve maintained this unique, signature balance with David Sims over the years. What was it like working with him in the beginning?

“I knew him and David Yow from when they were in Scratch Acid, which was a great band. Very influential. Yow was the extroverted guy, and I used to see him around. Super-talkative. I had some leftover studio time from a previous band that I wanted to use up, so I approached Yow and said, ‘Hey, would you be willing to work on a project with me?’ Then he said, ‘Why don’t we get David Sims, also?’ I thought I struck gold, man. I got two of the guys from Scratch Acid!”

“I loved working with David Sims. He was on the same wavelength. Organized. A ‘plan-your-work-and work-your-plan’ kind of guy. We seemed to hit it off right from the start. Our first rehearsals were in an abandoned house [in Austin] where the electricity hadn’t been shut off yet.

Even though we were doing digital, we recorded as if it was analog. In other words, we were all set up in the room and playing at the same time

“A friend of mine lived down the street and said, ‘These people moved out, and I think the juice is still on. You guys can probably go in there.’ And we did! It was a couple of amps, a drum machine, and us. We actually recorded there, too, and it sounded pretty good. [Those songs ultimately] became the first EP [1989’s Pure].”

Most Jesus Lizard records were made in Chicago. What was it like recording out of Nashville this time around?

“We had Paul Allen producing, a very experienced Nashville session guitarist. He was a fan. I’ve known him for years, and he knew how we had recorded in the past. Even though we were doing digital, we recorded as if it was analog. In other words, we were all set up in the room and playing at the same time.

“Sure, you do overdubs, but you get those basic takes and you decide right then and there, ‘that’s the take; we’re going to keep that.’ We did this whole album in about two weeks, start-to-finish. This was at Patrick Carney from the Black Keys’ home studio [Audio Eagle]. He had some top-notch gear.”

What were you running?

“I brought some of my own stuff. There was a Hiwatt Little J and a 2x12 cab; two Fender Supersonics; I like Blackstar, too. But then we go to Patrick’s, and he’s got a beautiful early ’60s Fender Bassman, and old Marshall Super Leads – like classic Plexis; not reissues. I might’ve thrown a Vox in there somewhere. Just beautiful-sounding stuff.

“It turned out to almost always be either the Marshalls or the Fender Bassman, with the Helix in front of it. I also have some outboard pedals that I like for drive: the good old Menatone Red Snapper; the Chandler Tube Driver; the OCD is one of the best. Patrick had a bunch of guitars, but I didn’t use any of them. I just used my own.”

You’re an aluminum-neck player, mostly?

“I go back and forth between aluminum and wood, and always have. Even before I was even in the Jesus Lizard, I had heavy, clunky Kramers. Then I went to wood. When we started the Jesus Lizard, I was playing a Yamaha SG-type, like my English hero John McGeoch from Siouxsie and the Banshees.

“Somewhere along the way I discovered Travis Bean aluminum necks, but once again, heavy and clunky. Serious neck and shoulder problems. On this album I used an all-aluminum Electrical Guitar Company Chessie, my model. I used a Fender Uptown Strat on a few things, too.

“For the live shows, though, I’ve been playing a Powers Electric A-Type, and they’re catching on, man. It’s wood, and it’s got some structural things going on that are amazing. It’s got trestle bracing. These are single coils; they’re virtually silent [yet] really high-output and nasty. You’ve got a compound radius fretboard. And it’s very light. Mine’s in London Grey.”

We’d be remiss to not point out in a Guitar World interview that this a record called Rack. You used to run mounted effects in the ’90s, right?

“For a long time, I was all-in on TC Electronic. Like a lot of guys, I started off with their very basic chorus/flanger/pitchmod pedal; then I went to the next level of TC: their 2290, a classic delay-and-modulator kind of thing. Then I went to the TC G-Force rackmount, which I still have. It’s got some sounds in it that I can’t get anywhere else.

“But then Bill Kelliher from Mastodon said, ‘Have you tried the new Line 6 Helix?’ I mean, it does a lot of stuff that I’ll never even use, but it’s got so much to it, and I really like that. And then for a backup I just bought the new POD Go, which has the same sounds in it, but it’s smaller. Those are floor things, though; I’m not into the rackmount stuff anymore.”

Since you mentioned Rack’s Grind earlier, that song has got the record’s most cookin’, extended solo runs in it…

“That solo comes right out of my rhythm playing. That was all live, straight up in the studio in a continuous pass. It’s funny, Mac’s hitting so hard that at the end of the solo – when I hit the open E string and it’s kind of hovering and starting to fade – you can hear the air pressure of his kick drum making my notes go, ‘boomph, boomph, boomph.’ Like, I couldn’t make that happen any other way. It was a weird acoustical phenomenon. Neat little things like that happen throughout the album.”

While there are moments on Rack that hit that classic Jesus Lizard aesthetic, you said that was just a starting point. What are some of the weirder pivots of the record, to you?

“The weirdest is What If? It’s slower, very atmospheric song. It’s got a triple meter; it’s got clean guitars almost all the way through; the vocals are spoken word! It was a left turn, but it came together quickly, which to me is a good sign. And then there’s the last song, Swan the Dog, where I used a Taylor T5z, an acoustic-electric. I wouldn’t necessarily call that acoustic, but that’s the first acoustic-ish guitar on a Jesus Lizard record. So yeah, we took some twists and turns.”

It took 15 years of the reunion phase to get a new album out of the band. How does it feel to have actualized new Jesus Lizard material?

People are so happy to hear that we’re back. We’re all super-psyched about this album

“Oh, it’s the best feeling in the world. You know, I’ve done a lot of stuff since we last did a record – I’ve done five albums with Tomahawk; I did some one-offs with other projects; I’ve played on sessions for other people. But to have the Jesus Lizard back? It seems like there’s a level of excitement I didn’t quite see with the other projects. People are so happy to hear that we’re back. We’re all super-psyched about this album. We want people to hear it, and we want people to come and see us.”

Yow’s still getting out in the crowd, but how much action are you seeing onstage? Any accidents or mishaps?

“There’s been some altercations over the years that we’ve all been involved in – pushing and shoving; maybe the odd punch. I try to avoid that these days, for a lot of reasons, but there was a time when that was part of the job.

“People want to get onstage and stagedive, but if you run into me, you’re not coming back. Like, don’t run into us; don’t trip over the pedals. That’s half the reason I didn’t use pedals for years – it was just chaotic mayhem. I feel like, ‘You know what, if you want to get on stage, go out and get your own band together.’”

Is there a head-shaped dent in one of your old Travis Beans?

“There’s a Travis Bean-shaped dent in someone’s head, more like it. Those things don’t dent easily.”

- Rack is out now via Ipecac.