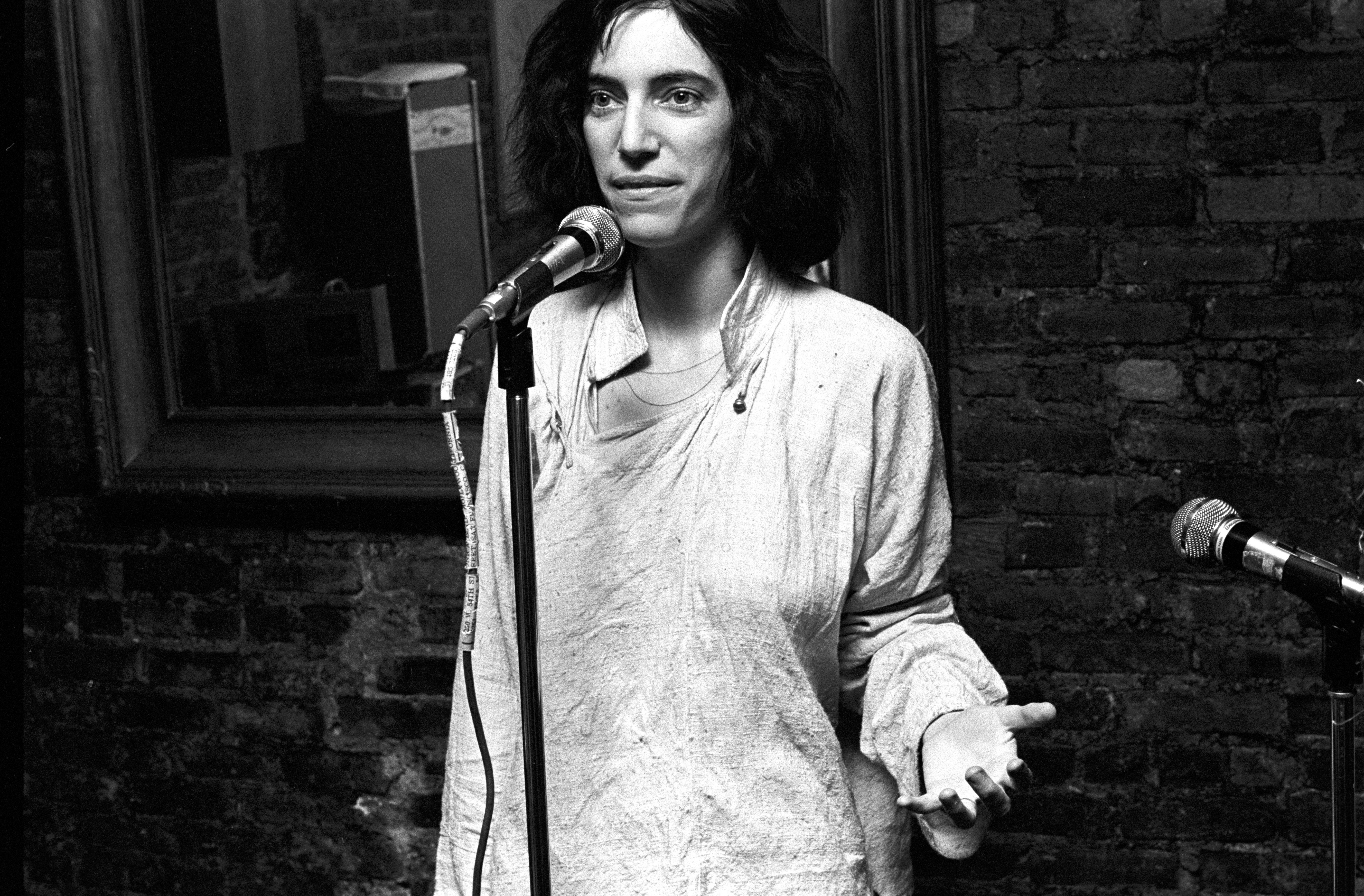

Patti Smith never planned to front a rock band. In 1971, when the music producer and manager Sandy Pearlman approached her about making music, she laughed and told him she had a perfectly good job in a bookstore. Pearlman had seen her performing her poems at St Mark’s Church in New York’s Bowery against a backdrop of feedback courtesy of guitarist Lenny Kaye. (Also in the audience that night: Lou Reed, Andy Warhol, Todd Rundgren, Sam Shepard and Smith’s ex-boyfriend, the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe.) In Smith, Pearlman saw a rock star in the making, but it took four more years for Smith to warm to the idea. Finally, in 1975, her first LP, Horses, was born.

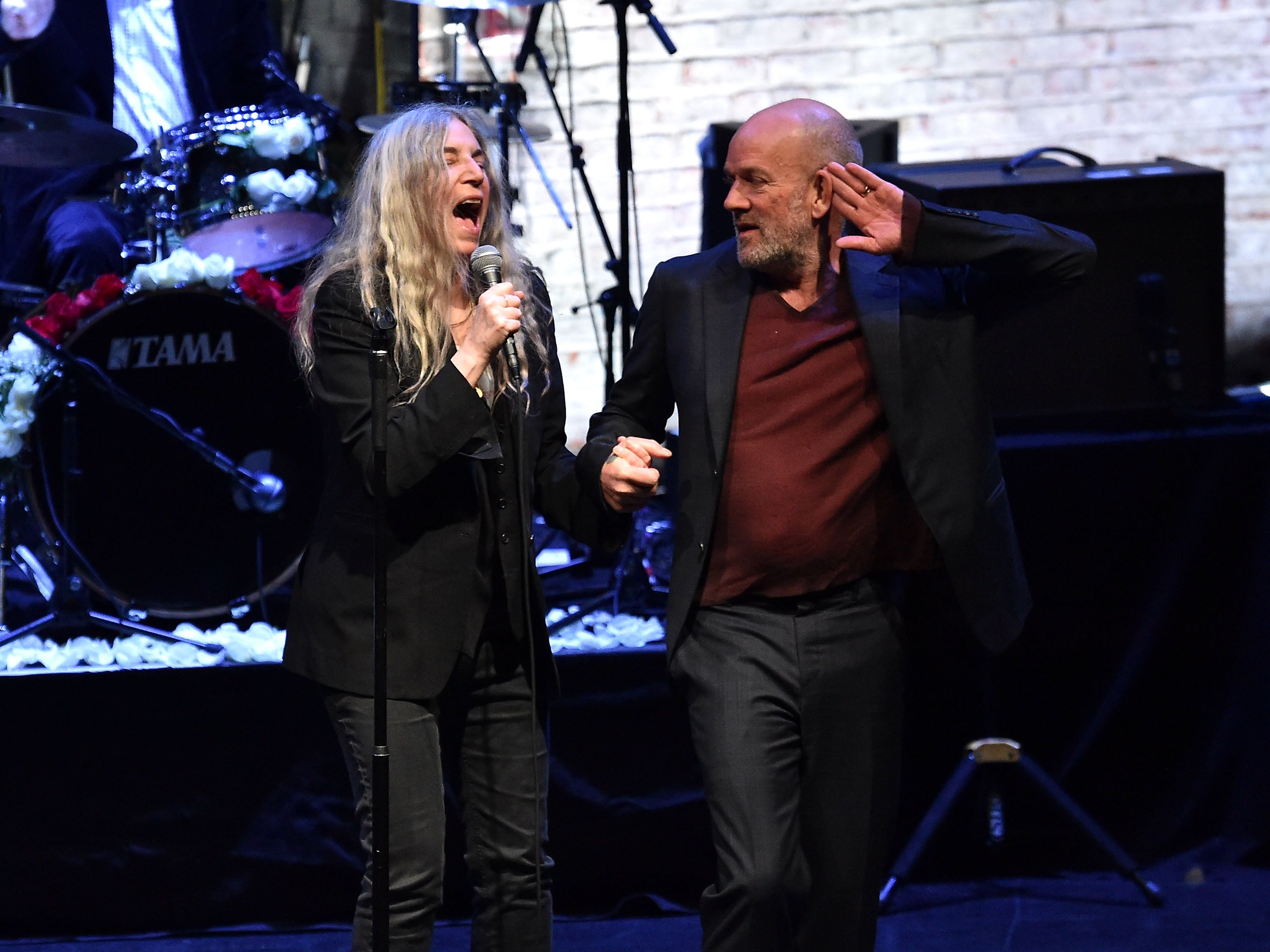

This November, Horses will be 50, an anniversary that is being honoured first with a tribute concert this month at New York’s Carnegie Hall featuring Michael Stipe, Kim Gordon, Karen O and more, and in the autumn by Smith herself in a string of concerts where she will perform the album in its entirety. Horses – which is included in the National Recording Registry in the US Library of Congress for being a record that’s considered “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant” – was not only one of the most explosive debuts of the 1970s: it lit the touchpaper for the New York punk rock scene. It arrived five months before the Ramones’ self-titled debut, and two years ahead of Richard Hell’s Blank Generation, Sex Pistols’ Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols and Television’s Marquee Moon.

In her 2019 book Revenge of the She-Punks, the music journalist Vivien Goldman describes Smith as “a new breed of autonomous, self-defined and uninhibited female rock star”. At the time, Smith didn’t give much thought to being a woman in a male-dominated scene – at least, not until men started shouting “Get back to the kitchen” at her during gigs. In the sleeve notes to Horses, she wrote of being “beyond gender”, later explaining that as an artist “I can take any position, any voice, that I want”. Nowadays she is often called the godmother of punk, or punk’s poet laureate, yet it is men who still dominate accounts of the scene.

But it would be wrong to attribute that entirely to misogyny. Smith may have provided a template for a new generation of musicians, but musically she existed in a category of her own; you might call it “punk adjacent”. Horses had a furious passion, and cared little for musical proficiency, but it didn’t sound like the work of a snotty upstart reflexively railing against authority. Instead, it bridged the gap between punk rock and poetry, with vocals that shifted between singing and spoken word. Smith was loud in her appreciation of writers and poets such as Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Blake, Genet, Plath and her beat-writer friends William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg. As she noted in her 2010 memoir Just Kids, when it came to making music, poetry was her “guiding principle”. Horses was, for her, “three-chord rock merged with the power of word”.

Prior to releasing the album, Smith had taken her first steps as a recording artist with a cover of Jimi Hendrix’s “Hey Joe” in 1974, about a man on the run after killing his wife, but with the murderous protagonist replaced by the kidnapped heiress Patty Hearst. It was decent, but it was the B-side that gave a glimpse of what was to come. “Piss Factory”, a raw, incantatory track that started out as a poem, and that recalled her time working in a New Jersey factory aged 16, was Smith’s cri de coeur against production-line drudgery. She had been mercilessly bullied by her colleagues, who were annoyed by her insistence on carrying a copy of Rimbaud’s Illuminations in her back pocket and instructed her to leave it at home. When she refused, they dunked her head in a toilet bowl of urine to teach her a lesson.

Smith’s lyrics on Horses would prove similarly visceral, never more so than in the opener “Gloria (In Excelsis Deo)”, a reworking of a Them B-side that wove in excerpts from Smith’s poem “Oath” and began with the electrifying refrain: “Jesus died for somebody’s sins, but not mine”. More than just a rejection of religion, it was a perfect distillation of Smith’s spirit: hypnotic, primal, uncompromising. Elsewhere on the album, there are tales of female suicide (in the reggae-inflected “Redondo Beach”, wrongly interpreted as a same-sex love song at the time), alien visitations (“Birdland”) and a dream in which Jim Morrison of The Doors is bound like Prometheus on a marble slab, only to break free (“Break It Up”). In “Free Money”, the most straightforwardly propulsive rock song on the album, she dreams about winning the lottery, climbing out of poverty and “buy[ing] you a jet plane, baby”.

Horses was recorded at Electric Lady Studios, near Smith’s New York apartment. Among the musicians were Kaye, Television’s Tom Verlaine, Allen Lanier, Smith’s then boyfriend from Blue Öyster Cult, drummer Jay Dee Daugherty, and Richard Sohl on keyboards. Together, they fashioned a spiky garage-rock sound partly honed during live performances at the soon-to-be punk mecca CBGB, and that would become the signature sound of the late 1970s scene. John Cale of the Velvet Underground, the producer, encouraged improvisation in the studio and avoided smoothing the band’s rough edges. Even so, he and Smith clashed repeatedly during the five-week recording, with Smith saying it was “like [Rimbaud’s] A Season in Hell” for them both. Cale later recalled the experience of working with her as “confrontational, and a lot like an immutable force meeting an immovable object”.

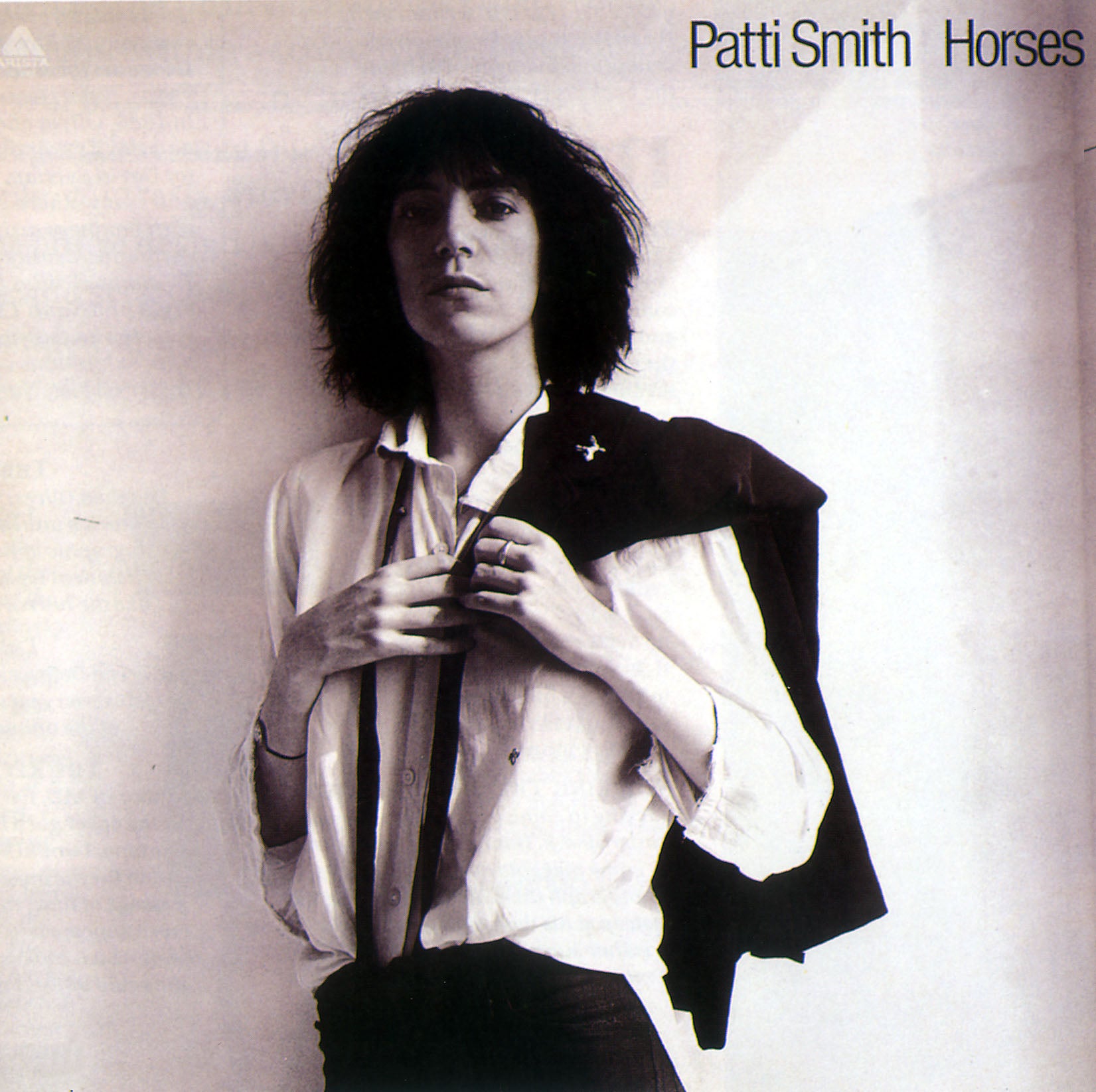

Smith’s transgressive spirit also inhabited the cover image, which reinforced her “beyond gender” approach. Taken by Mapplethorpe and shot in black and white at a penthouse apartment owned by the art curator Sam Wagstaff, it showed an androgynous-looking Smith in white shirt and slacks, a jacket slung insouciantly over her shoulder as if she were the sixth member of the rat pack. When Smith’s label, Arista, suggested the hair on Smith’s upper lip be airbrushed out, they might as well have asked her to don heels and a sparkly dress. She instructed them to leave it be.

When Horses came out on 10 November (the death date of her beloved Rimbaud), Smith had already published several poetry collections and was making money writing for music magazines including Creem and Rolling Stone. In her early years in New York with Mapplethorpe, the pair had lived in squalor and often couldn’t afford to eat, but by now she was comparatively solvent. With her album finished, she imagined she would keep on writing and perhaps go back to working in the bookstore. As she told an interviewer in 2007, rock’n’roll was something she was “just gonna do for a little while and then get back to work”.

What she didn’t bet on was the album’s rapturous reception, which led to requests for her to perform all over the world and to record more music (one of the few dissenting voices was that of Greil Marcus, who snippily declared: “If you’re going to mess around with the kind of stuff Buñuel, Dali and Rimbaud were putting out, you have to come up with a lot more than an homage”). In the five years after Horses was released, Smith would make three more albums including 1978’s Easter, her most commercially successful LP. Easter included the single “Because the Night”, an air-punching ode to love and hedonism that was co-written with Bruce Springsteen. It remains Smith’s biggest hit. Fans accused her of selling out, but she was unrepentant. She told New York Magazine: “I liked hearing myself on the radio. To me, those people didn’t understand punk at all. Punk-rock is just another word for freedom.”

To me, those people didn’t understand punk at all. Punk-rock is just another word for freedom

Smith was still on a commercial high when, in the late 1970s, she retreated from the limelight. By this time, she had met her husband, Fred “Sonic” Smith of the Detroit band MC5, and was pregnant with their first child. For the next 15 years, she would concentrate on raising their two children; aside from 1988’s Dream of Life, made with her spouse, there would be no new music. But then, in 1989, her former soulmate Mapplethorpe died from an Aids-related illness at 42. Five years later, her husband and her brother both died within a month of each other; both were in their forties. As the sole breadwinner, Smith had no choice but to go back to work.

Now 78, Smith has outlived most of her New York contemporaries, bar Kaye, who still performs with her, and Cale, with whom she has long made up since those fraught Horses sessions. Her work transcends not just genres but mediums too. The last 15 years have seen her triumph as a memoirist: the award-winning Just Kids, a chronicle of her relationship with Mapplethorpe, is a bona fide masterpiece, a poetic account of youthful love, and a deliciously grimy portrait of the late 20th-century New York scene where music, art and literature collided and culture was remade. Her two subsequent memoirs, 2015’s M Train and 2019’s Year of the Monkey, provide portraits of the latter-day Smith: always writing, photographing, performing, tending to her cats and paying loving tribute to the artists, dead and alive, who paved the way. Not for nothing does she have the rare distinction of having been awarded an Ordre des Artes et des Lettres by France’s ministry of culture for her poetry and, for her musical achievements, a place in America’s Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

The influence of Smith on successive generations cannot be overstated: The Clash, Sonic Youth, Madonna, Courtney Love, Michael Stipe, PJ Harvey, Florence Welch, The Raincoats, Bikini Kill and The Waterboys’ Mike Scott have all talked of their debt to her. Stipe said that when he heard Horses, it “tore my limbs off and put them back in a whole new order”. Go to her concerts now, and you’ll see old punks standing in rapturous communion alongside teenage and twentysomething fans all celebrating Smith: an accidental icon and rock’s most remarkable renaissance woman.

‘People Have the Power: A Celebration of Patti Smith’ is at New York’s Carnegie Hall on 26 March. Smith performs ‘Horses’ in full at the London Palladium on 12 and 13 October. Tickets here.

Can Michael Jackson’s music survive the accusations against him? It’s complicated

Tom Petty guitarist Mike Campbell: How ego, heroin and a hot temper nearly wrecked the Heartbreakers

Neil Young – has the godfather of grunge just given us the first Maga anthem?

‘I get PTSD when I watch it’: The inside story of the outrageous music doc Dig!

Louise: ‘For years I wasn’t scrutinised. Then bang – everybody had an opinion’

It it still OK to listen to Michael Jackson? It’s complicated