Ask any WorldTour pro rider or mechanic, and they'll tell you that Paris-Roubaix is the toughest and biggest race of the year. Sure, races like the Tour de France last three full weeks, but the brutality of the Hell of the North is without equal in professional cycling.

Paris-Roubaix is one of the most interesting races of the year for tech, and by and large, you can always expect something new or for a team to experiment a little bit, here are our tech predictions for this year's race.

As fifty-year veteran pro mechanic Julien Devriese, who wrenched for such legends as Eddy Merckx and Greg LeMond, puts it, "Roubaix is not a race where you have fun. You can work eight days for Paris-Roubaix and all the work can be for nothing by the first cobblestones."

The cobbles of Paris-Roubaix are among the roughest that road bike racing has to offer. Likened by many to a mountain biking rock garden more than a road, the sectors of cobbles in Northern France are a savage test for both the rider and their equipment.

But designing the perfect Paris-Roubaix bike requires a fine balance. Bikes must be able to handle this terrain at speeds of 50km/h or more, across 30 sectors covering 55km of cobbles within a route that tackles 257.7km in total. But they cannot be set up purely for speed on the cobbles, because that'll come at a detriment of speed on the remaining 250km-plus of smooth tarmac. Optimise too heavily for the smooth roads, though, and you risk failure altogether when the going gets rough.

As Bahrain-Victorious mechanic, Žarko Poštić told us when we spoke to mechanics at the 2024 edition of the race

"You have to remember, the cobblestone parts of Roubaix make up part of the last 100km, the 160km to get there is road, so you need to strike a balance between the two."

For decades, bike manufacturers have tried to tread this line while simultaneously pushing the boundaries to one-up their competitors to achieve a 'best of both' solution and provide riders with the right amount of comfort. There has been a range of innovative, eye-catching and downright wacky designs and tech over the years.

One recent example of innovation came just last year. Two teams trialled an innovation which could adjust tyre pressures on the fly. A handful of the Jumbo-Visma team (now Visma-Lease a Bike) used the Gravaa KAPS system to varying degrees of success, while Team DSM (now DSM-Firmenich) trialled the Scope Atmoz system in the lead-up, but ultimately decided it wasn't ready for use in a race.

But we're getting ahead of ourselves. Let's take a step back in time and look at some key examples of Paris Roubaix bike innovation.

The technological arms race

Cycling has always been a display of impressive leg power, but that doesn't stop the arms race (see what we did there?) from being important. Since the earliest days of the race, riders and teams have been searching for a mechanical advantage over their rivals.

In times when the bike's ability to survive the race wasn't necessarily a given, the technological advancement was primarily about increasing the likelihood of making it to the finish. For almost the first 100 years of the race, riders and teams looked to things such as stronger tubes and more durable equipment to prevent frame failures. However, narrow rims and skinny tyres were the order of the day,

But as time went on and equipment improved across the board, there were also comfort considerations: double-wrapped bar tape, slacker angles and bigger tyres were all aimed at smoothing out the terrorising terrain and helping riders feel more comfortable and carry more speed on the cobblestones.

But in 1991, things stepped up a notch when Greg LeMond and Gilbert Duclos-Lasalle (Team Z) debuted RockShox's new suspension fork. With 30mm of travel, it provided much-needed relief over cobblestones for its users, but this too-fast-paced advancement was met with strong opposition.

Duclos-Lasalle eventually enjoyed the last laugh though, and when he rode his suspension-equipped LeMond to victory in 1992, the technological floodgates were opened. This coincided with an era where technological advancement was gaining traction in all road cycling segments, with Chris Boardman's Lotus 108 challenging the rules on the track, and various riders beginning to understand the benefits of aerodynamics in time trials.

In 1993, no fewer than five teams and countless individual riders showed up with the same RockShox fork, yet it was Duclos-Lasalle that would win again, beating Franco Ballerini (GB-MG Maglificio) in a photo finish.

Further bump-smoothing tech would begin to appear, including suspension stems to try and curb the RockShox monopoly, and despite Andrei Tchmil (Lotto) taking victory on a Caloi with, you guessed it, RockShox forks, but it would be something altogether more radical that would be remembered almost 30 years on.

Look out gravel fans, there's a theme brewing

Anyone who has followed the rise in gravel bike tech may have noticed the parallel between the early '90s Paris-Roubaix bike evolution and the trends followed by today's gravel bikes.

Road bikes with slacker angles and longer wheelbases happened almost a decade ago with the rise of the 'endurance' category. Then wider tyre clearances appeared and gravel bikes became a thing, with 'road plus' or 'all road' filling the gap between the two. SRAM's 2021 XPLR launch saw the inclusion of a gravel fork - the RockShox Rudy - which comes with, you guessed it, 30mm of travel. So what's next?

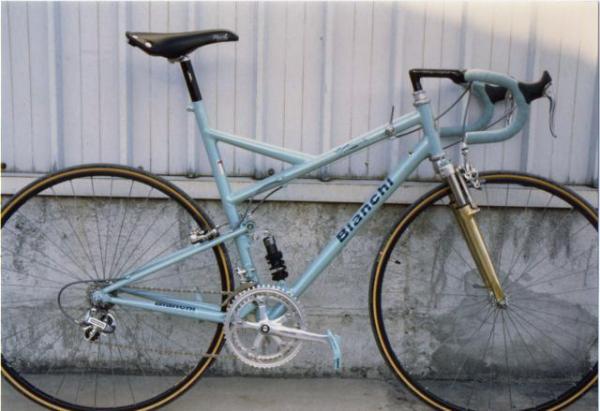

In that 1994 edition of Paris-Roubaix, it wasn't the third-straight victory for RockShox that people remember. Nor was it the 67km solo attack that saw the Moldovan Tchmil take victory (impressive as it was). Most memorable was the disappointing 13th place taken by Johan Museeuw (Mapei), for it was his full-suspension Bianchi road bike that cost him.

Road bike suspension for Paris-Roubaix had truly earned its legitimacy by this point, with two victories on the bounce, so brands looked to the rear of the bike to add an extra level of plushness, and numerous iterations of full suspension road bikes were seen on the start line that year. Duclos-Lasalle and LeMond were aboard custom Clark-Kent titanium frames with a unique 'softail' design, but Bianchi took things a whole lot further.

Taking a mountain bike design that was already in development, Bianchi gave its Paris-Roubaix bike a single-pivot swingarm and short aluminium seat-tube-mounted rocker link, which drove a small coil-over shock, resulting in what can only be described as a mountain bike with drop bars and skinny wheels.

Returning our minds to the gravel bikes of today, one can't help but think of the full-suspension Niner MCR 9 RDO, which has been around - albeit uncopied - for a number of years already. As well as the Specialized Diverge STR, and the more subtle Reverb XPLR seatpost from RockShox, which offers small-bump compliance in addition to its dropper-post abilities.

Sadly for Bianchi, that radical design proved too radical - or at least too poorly executed - as it failed catastrophically costing Museeuw a chance at the win.

With less than 24km remaining and lagging behind Tchmil by 41 seconds, Museeuw's drive-side chainstay snapped clean through. A subsequently botched bike change complicated by a jammed clipless pedal ended his chances at victory (though he would go on to win three times).

"That was my first full-suspension design for Bianchi, the one that Museeuw rode to eventual embarrassment at Paris-Roubaix," said Matt Harvey, product manager for Bianchi USA at the time. "I eventually did two designs at Bianchi, but this one was probably the best. [It was] a two-inch short travel design that could be used for cross-country MTB and a road bike. It only had two pivots, relying on the seat stays to flex a couple of degrees, making a much stiffer rear end that didn't wag around. This was also the eventual problem because a Chromoly rear end can flex thousands of cycles this small amount, whereas the Italian factory, against my pleading, made it out of 6061 [aluminium] without heat treating it.

"There was a pretty sharp bend to clear the chainrings from the pivot point, about three inches back," Harvey continued. "The problem was when they assembled it, the Dura-Ace bottom bracket was so narrow that the inner chainring was rubbing on the stay so they simply put a rag in the vice and squeezed it."

This sparked the beginning of the end for suspended bikes at Paris-Roubaix. Even the then-successful RockShox forks failed to gain another victory and eventually fell out of favour.

Fast forward to 2005, and suspension design was relaunched into the spotlight when George Hincapie (Discovery Channel) finished second on a prototype design from sponsor Trek, who again revisited the softail concept.

This concept known as SPA (Suspension Performance Advantage), was developed by Trek subsidiary Klein, and incorporated a simple elastomer-type shock between the seat tube and the seat stays of the team's carbon frames. Chainstay flex provided 13mm of rear-wheel travel, and the absence of true pivots helped keep the back end in line under power.

This concept of flex stays is once again being revisited in gravel bikes, with Cannondale's 'Kingpin' technology on the Topstone being one such example.

"The bikes were a success with the riders," said then-team liaison and current Trek race department manager Scott Daubert. "They claimed that the bikes carried more speed across the cobbles. They also claimed to have better control on the pavé. Our selling point was that they would be less fatigued toward the end of the race but that was hard to quantify. Roubaix takes its toll no matter what."

So it seemed that suspension was again proven successful in the sport's toughest one-day event. The design has been repeated a few times, most notably by Pinarello with the K8S in 2015, but even so, the concept never fully took hold.

"I can't think of any one reason that SPA isn’t a part of today’s race bikes. Distinct tube shapes and specific carbon lay-ups is our current way of thinking. Shapes and lay-ups are more difficult to develop but yield lighter and more efficient frames."

Back to basics

Indeed, in the years since, the evergrowing understanding and advancement of carbon fibre technology have yielded enormous benefits in a bike's ride characteristics. The industry often jokes that every new bike comes with a tagline of 'stiffer, lighter, faster and more compliant', but over the years, each iteration of improvement means that today's road bikes are truly able to handle the cobbles of Paris-Roubaix without the need for front and rear suspension tech. That's not to say it's not still in use, but now we're getting ahead of ourselves.

Despite Trek's foray into suspended stays, the mid-noughties primarily saw a return to basics, with an increased focus on maximising the capabilities of carbon fibre.

Cervélo set the bar first with its groundbreaking R3 model, tweaking the proven formula with 1cm of additional chainstay length plus a generous 50mm of fork rake to maintain proper weight distribution between the wheels. That combination kept all of the responsiveness and compliance of the proven giant chainstay/tiny seatstay design but added the toned-down handling and tyre clearance needed to win cycling's toughest one-day race. It's a concept that is still being replicated today and formed the inspiration for Cervélo's Caledonia.

Fabian Cancellara would earn the R3 its first victory in 2006 with Team CSC, followed by teammate Stuart O'Grady on the same machine one year later.

For the next three years, Specialized dominated the race with its aptly named Roubaix, piloted by Tom Boonen twice and then Fabian Cancellara in 2010. Boonen's bike featured special geometry to suit his unusually long-and-low position but even the bike's stock geometry catered to comfort, control and compliance.

There were also some new features integrated into the frame specifically designed to help quell the debilitating vibrations of the cobbles. Zertz inserts, as they were known, were small elastomers within cut-outs in the carbon frame. They were claimed to allow the carbon to flex more than it otherwise would but in a controlled manner. Specialized stuck by Zertz technology for nearly a decade, before dropping it in favour of its Future Shock headset technology.

Niki Terpstra, riding for Quick-Step Floors at the time, decided he didn't like the squishy front end that the Future Shock provided on his Specialized Roubaix bike, and swapped it for an untested prototype rigid replacement. The prototype infamously failed, causing him to crash and end his race.

As bikes have progressed the Specialized Roubaix has largely been ditched by the pros as they look for all-out speed, more on this further on. In 2024, it was confirmed most Specialized teams wouldn't be racing on the Roubaix model anymore.

But where there are cobbles, there will always be a desire to make them smoother, so in 2013, Trek's Domane introduced IsoSpeed, which featured a pivot point at the seat cluster to facilitate and invite flex, thus allowing the saddle a small amount of movement when under the rider's weight.

Since then, advancements have included the ever-widening tyre clearances. Anything above 25mm was a rarer sight before 2010, and then sizes up to 27mm began gaining popularity in the early 2010s. 28mm was the limit for a while, but things are now a lot wider and only heading one way.

Disc brakes simplified things, but you'll never stop innovation

The introduction, adoption, and now complete domination of disc brakes in the pro peloton is in no way directly related to the demands of Paris-Roubaix, but it's certainly aided the innovation, while simultaneously changing its direction.

Without the constraints of a rim brake caliper enshrouding the rim and tyre, tyres have been freed from their shackles and have grown in size as a result. Nowadays it's not uncommon to see 30 or even 32mm tyres in the race, and some race bikes can handle 34mm tyres; ironic given cyclocross tyres are limited to 33mm.

As bikes have become more and more versatile, there has also been a move away from specialist bikes for the terrain in the search for all-out speed. For example, Sonny Colbrelli won the sodden 2021 edition aboard a Merida Reacto aero bike with no clever bump-smoothing tricks besides wider tyres (mixed reports have them between 30 and 32mm). Notably, Mathew Hayman was the first to win on an 'aero bike' with the Scott Foil in 2016.

Nowadays it's the smaller things such as chain catchers, wide tubeless tyres with foam 'inserts', double-wrapped bars and pieces of handlebar tape on computer mounts to prevent rattles that set Paris-Roubaix bikes apart from those raced at 'regular' road races. Rather than radical redesigns, dual-pivot swing arms, or front suspension resembling a mountain bike fork.

But 2023 saw attention shift towards the tyres, with the Gravaa and Scope systems both aiming to let the rider deflate and inflate their tyres while moving, allowing for lower pressures (and thus, a smoother ride) on the cobbles, before returning to higher pressures for the roads to maximise efficiency overall and potentially save a lot of watts on the cobbles. The systems weren't adopted for races and we heard rumours it took too long for pressure changes to happen, it looks like further developments have been made in this area though and the tech has been used in competition this year.

Separately, the past few years have seen the rise of single chainring setups, commonly known as 1x. Given Paris-Roubaix is largely a flat race, there's no real need for a second chainring at the front, so riders have been swapping to the lighter, more aerodynamic single ring, replacing the derailleur with a chain catcher just to keep things secure on the cobbles.

Riders' attentions have grown far beyond the bike itself, too. Clothing, helmets, and every aspect of performance are being optimised to the Nth degree to find an advantage, but we'll save the deep dive there for another day.

The future is bright, the future is... normal

Despite gravel bikes diverging into subcategories, gravel race bikes becoming more widely available, and their evident suitability to the rougher terrain found in Paris-Roubaix, this isn't where the future of the Paris-Roubaix bike lies.

We have seen it coming for a few years, but for the most part, at least at the moment, the race bikes used at Paris Roubaix are just that, race bikes.

Bikes are just so capable now that pro riders can use the fastest option available and thanks to larger tyre clearances, wider wheel rims and bigger tyres can be faster on the cobbles than the 'Roubaix specific' bikes of old. As we learnt from speaking to teams and riders last year, no one wants to sacrifice speed now and they don't have to.

Probably the best all-around example now of the latest cobbled race bikes are the Trek Madone bikes used by Lidl-Trek for the classics, the team's riders use the 1x13 SRAM Red XPLR gravel-specific groupset which uses a 10-46T rear cassette with a single front chainring at around 54T in size.

The Red XPLR derailleur is oversized and uses a very firm derailleur arm spring tension to really help eliminate chain slap and even dropped chains on the cobblestones. The narrow-wide 1x chainrings up front also aid chain retention, it's something of an ideal setup for the cobbles.

Paired with wide wheel rims and 30-35mm tubeless tyres at lower pressures, the bikes are as fast as they have ever been on the cobblestones. We expect the largest tyre size this year to be around 35mm.

Nothing stays the same, and tech advancements over the next few years will probably see Roubaix bikes get even faster and more capable. The Hell of the North is a stern test and the quest for all-out speed on the cobblestones is unrelenting.