Paranoid London – the duo consisting of Quinn Whalley and Gerado Delgado – are an example of how success can come from sticking to your guns and doing what you do well.

Their sound is defiantly old school, a raw and unpolished take on acid house and techno, created by the interplay of hardware synths and drum machines with oddball sequencers and effects units. With little in the way of industry support, the pair have become cult heroes in the UK underground on the strength of their vibrant electronic jams and energetic live shows.

The band have also become known for their diverse and exciting pool of collaborators. New album – the excellently titled Arseholes, Liars and Electronic Pioneers – sees the pair working with the likes of rising house star Josh Caffe, Berlin musician Jennifer Touch, Chicago’s DJ Genesis, and Primal Scream frontman Bobby Gillespie.

We met up with Quinn Whalley in the band’s envy-inducing gear cave of a studio to find out more.

Can you tell us how Paranoid London started out?

“About 20 years ago I used to do this thing, what we used to call engineering. There were a bunch of people like me that knew how to connect MIDI cables and set up scuzzy effect chains and stuff. We would charge DJs, like, £200 to come to our studios, and they would bring a bunch of records, which we’d sample up for them and make them a track. There were loads of us that used to do that, basically just supporting our hobby of being in this studio.

“Del had tried working with a few other people, but it hadn’t worked. Then we got put in touch through a friend of mine, Justin Drake, who I used to do music with. At this point, me and my mate had just opened a studio and we had nobody coming in.

“We were completely broke, and I had loads of time. Del lived in Tenerife at the time. He would come over about four times a year and we’d get in the studio. He’d bring a bunch of records, and each time it would be different. It would be whatever he was into at the time. He used to work in FatCat records, and he was a brilliant DJ, so he had a really good record collection. One time he might come over and say he wanted to make something like a Danny Tenaglia tribal record, or it might be a Derrick Carter, bumpity‑bump thing.

“We were doing this for ages and he never put anything out. I started feeling bad about it. I’d say, ‘Mate, you keep coming down here and paying me to do this, but you’re not really happy with any of the stuff that we do’. We went back to his house one night and were getting drunk and talking rubbish, and I said to him, ‘What is it that you’re actually into?’ He said, ‘I’m just into banging acid house’. I said, ‘Yeah, me too. Why don’t we just do that?’ So we did.

“This was exactly the time that the arse had dropped out of selling records. Suddenly, nobody was buying any records. But the great thing about Del was that he didn’t care if nobody bought the record at all. He just wanted to do stuff that he liked, and couldn’t care less if nobody else liked it.

“I think the first record we put out was the heaviest vinyl you could possibly make. It was a really expensive record and there was only one side of it. All the distribution companies were like, ‘No, we’re not going to give you a P&D deal because, A, nobody wants this music and B, there’s only one side of it and it’s really expensive’. So Del just said he’d pay for it himself.”

Your new album is called Arseholes, Liars and Electronic Pioneers – how does the sound of the record tie into that title?

“We did the album but didn’t have a title. It’s the worst thing in the world, sitting there trying to think of a name for something. It just never happens. Again, I think we were maybe getting drunk or something and Del just popped out with it as a joke: ‘Why don’t we call it Arseholes, Liars and Electronic Pioneers?’ But it actually trips off the tongue quite nicely. And also there’s just loads of fucking arseholes and liars around at the moment, aren’t there?

We’re bombarded with them from every angle. Everything you see on television, our whole media is full of arseholes and liars. Our politicians are all arseholes and liars. But then there’s loads of these, like, really cool electronic pioneers. You know, women, black people, Latino people, blind people… They’re just way more fun and more cool.”

Tell us about the studio…

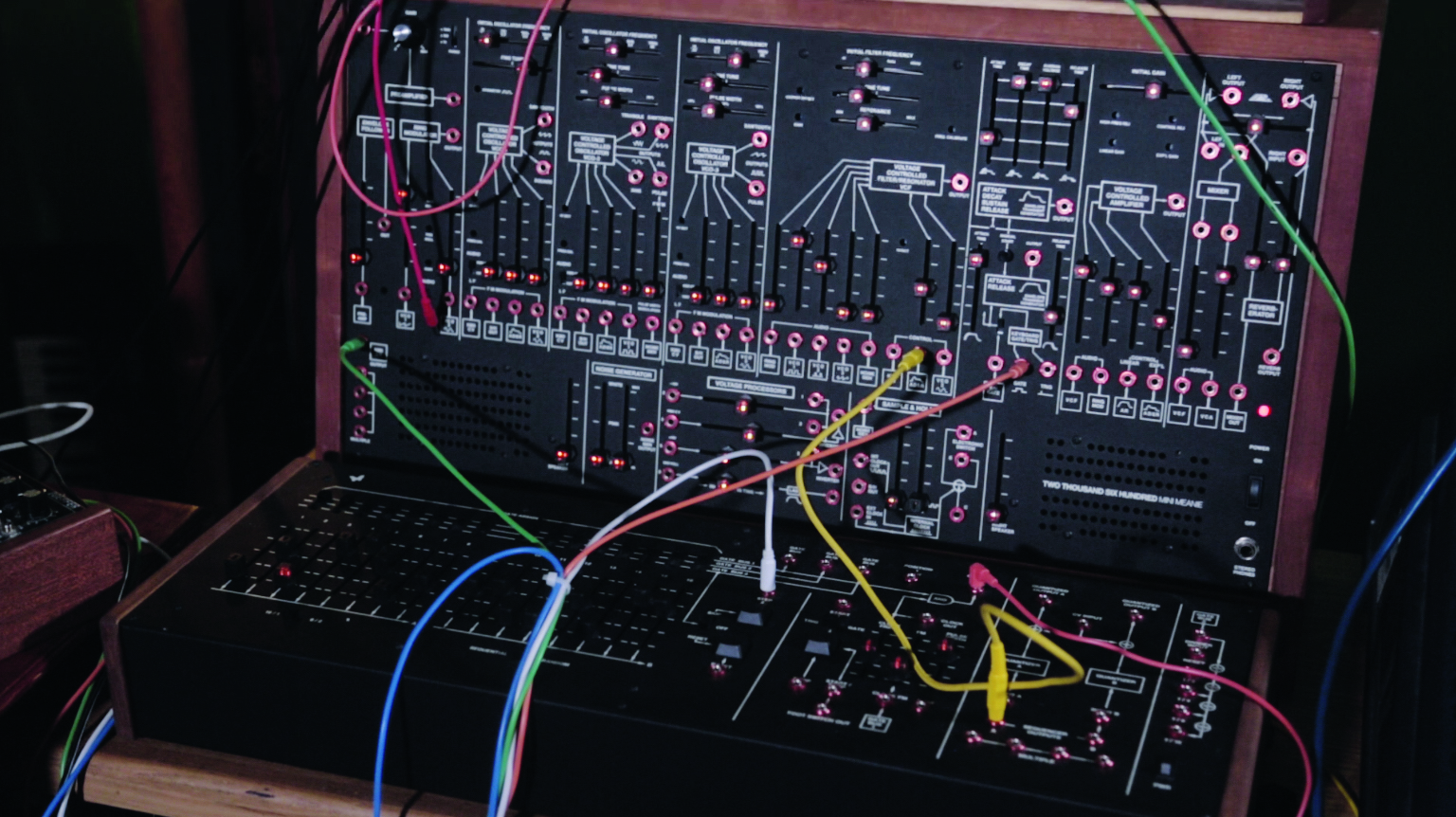

“I rent this room from Margo Broom, who’s an absolute genius. She builds synthesisers and drum machines and stuff like that. She built our ARP 2600 with the sequencer on it. We’re going mental on that at the moment, I absolutely love it – it’s brilliant. She’s always just coming in and dumping something that she’s either made or she’s bought. So we’ve got all this amazing stuff to play around with.

“We only moved in here just before we made the album. I’m not a massive fan of using loads of gear. Even though we’ve got lots of stuff in here, each time we do a track we’ll only have a couple of little things. For example, we know the 303 and the 808 inside out. We tend to stick with stuff like that, which we know, then add in other little bits and bobs in.

“Margo also got us the Sequential Circuits Pro One, which I’ve always wanted to have a go on. And lo and behold, it’s brilliant! That’s all over the album as well.”

What dream bit of kit would you love to add to the studio?

“Again, it’s from Sequential Circuits; the Studio 440. It’s the drum machine and sampler that Mantronix used to use. I remember it from when I was a kid, and he came over here on tour.

You’ve just got to do whatever you can with what you’ve got, really

“At that time, because there was no internet, you were desperate for any little bit of information you could find out about any equipment at all. He did a bunch of interviews on the radio, and he was on The Tube and stuff like that. And at one point he just mentioned the name of this thing, the Sequential Studio 440.

"He was going on about how he could sample stuff live. Bearing in mind at that time, it probably only had, if you’re lucky, four seconds worth of sampling time. You could only sample little drum noises and stuff like that. But yeah, just because Mantronix had it. I’ve always wanted a Sequential setup. I’ve never even been in the same room as one, though.”

You use a lot of classic hardware, but also have some modern emulations. What’s your view on how the two compare?

“We toured with our 808 for, like, 10 years. Just last year it started playing up. We’d do a soundcheck and everything would be great, then a couple of times when we came to do the show it just wouldn’t turn on. We used to take the 909 with us as well, but it was all too big to take in hand luggage on flights.

"In the end we had to do a couple of shows where we just had the Boutique 909 that Roland did, because our main 808 had broken, but since we only used it on one track we only had one pattern programmed into it. Luckily it was a really busy one. That’s the great stuff about having stuff with knobs on it; even with just one loop you can make it work for a whole show.

“We eventually decided we had to retire the 808 and get the Behringer ones. Because everything goes though the Korg Monotrons, which kind of distorts and compresses them, so when it goes through a massive PA it’s kind of alright.

“Annoyingly, our 808 is completely different to everybody else’s in the world. The snare drum and the kick drum on them are ridiculous. When we first had it fixed the guy opened it up and said that someone had done a load of weird stuff to it. Instead of using glue to fix it they’d used hairspray, or something like that. Basically the circuits on the bass drum and the snare drum go ridiculously long. So using other ones is not quite the same. We’ve started taking that out again now, though, as Margo’s sorted it for us.

“Really, though, it’s just about using whatever you can make a noise with. Because we couldn’t rely on that same 808, we just did different things on the Behringer. And that worked alright. You’ve just got to do whatever you can with what you’ve got, really.”

Tell us more about how the live shows work…

“We have the drum machines, as we’ve said. Whether that’s the Behringer one or the original 808, it goes into the Monotron Delay. Our 303 broke, again, because we were touring with it for like 10 years, so we’ve got one of those Cyclone ones. That’s pretty good. That goes into a Monotron as well. Then we’ve got a [Doepfer] Dark Time sequencer and our 202 that goes – funnily enough – into another Monotron.

“Then there’s a vocalist who goes into a Monotron too, then there’s some percussion loops and stuff like that. It all gets clocked from Ableton, and there’s some bits of samples and stuff that come through there. We sort of just mute and unmute stuff on the desk and muck about with it all, and off we go.”

Do you have a studio tip for our readers?

“Record everything. When you’re going to set something up, and you think that you’re going to use that, record you setting it up, because that’s the bit that’s great. The bit when you’ve got it, when you think that you know what you’re doing, that’s boring. It’s always the bit before, when it’s a bit out of tune and you’re still stabbing at buttons. Record everything all the time and keep it all.

"The good thing [about DAWs] is that you can drag something in that you did, like, three years ago. That might have sounded really boring over whatever you were doing at the time. But then if you take a bit of that, and put it over something that’s in a different tuning or whatever, that’s when weird stuff starts happening.”

How do you find the vocalists who feature on your tracks, and what’s the writing process with them like?

“We’ve always been really lucky with vocalists. Josh Caffe and Clams Baker – who does Mutado Pintado, or whatever name he’s going by this week – are ridiculous, you know what I mean? We’re really lucky. I’ve known Clams for 20 years or so. I used to play for him in his club in New York. And then we were in a band together, actually with the two guys that I now do Decuis with as well, but that’s another thing entirely.

“Then Josh Caffe I met through a guy who runs a party called I Love Acid, Josh Doherty. We just have a scream in the studio. It’s total chaos, and it’s a great laugh. In different ways, they’re both completely unique and individual. They’re not trying to sound like anyone else.

“The rest are just people that you bump into along the way. I don’t know. We just sort of happen across these people. For example, our manager knew Bobby Gillespie. It was his idea to get him to come down, which was amazing. He came down and at first we tried to do a techno thing with him. It was kind of all right; he was good, but couldn’t do anything that really fitted with it.

"So we said, ‘Look, why don’t we try an old, sort of like, Primal Scream, blissed-out thing?’ And he was like, ‘Yeah, yeah, cool.’ He went away and wrote this song. Then he phoned us up when we were in the studio, really excited about it and started playing it to us down the phone. We were like, ‘fucking hell, Bobby Gillespie’s playing us a song down the phone, this is nuts.’ He’d written that song, then he came down and recorded it.

“What we do a lot of the time is we’ll give someone a backing track to write to. We do something quite musical for them, so they’ve got something to sort of grab onto. Then we’ll take that all away and make something gnarly underneath. But then with a couple of the people, like Joe Love from [London band] Fat Dog, he came down here and we wrote together. Clams and Josh just come down and we’ll get really drunk and I just literally record everything they say. Then we’ll make something out of that.

“Jennifer Touch – we sent two tracks, and both times we didn’t even do anything to her vocal. What she sent us was brilliant. We just left it as it was. Jennifer lives in Berlin, so it would have been more difficult to write with her. Luckily, it turns out she’s amazing at writing songs and did it all on her own anyway!”

Arseholes, Liars… is available at Paranoid London's Bandcamp page.

Studio tip: Paranoid London