Hack Green Secret Nuclear Bunker seems to come out of nowhere as you drive deep into the Cheshire countryside.

It emerges suddenly behind chain link fencing: squat and yellow and ugly. It does not look like a 35,000sqft facility but then it wouldn’t – most of it is buried beneath the ground.

Today this place is not, as the name states, secret. It is, in fact, a family-run Cold War museum.

Behind its blast-proof doors and nine-foot concrete walls are displays explaining the conflict. There’s a shop and cafe.

But, if history had turned out differently, this would have been one of a dozen command centres from which the UK was run in the aftermath of a nuclear attack.

Some 135 government and military personnel would have lived underground here for three months following a strike.

A vast air purification system – still working – would have filtered the contaminated air from outside while huge underground generators would have maintained power supplies.

A massive storage pantry was kept permanently topped up with rations and two huge tanks with 30,000 gallons of drinking water. A cypher room, BT exchange centre and even a BBC studio were all installed.

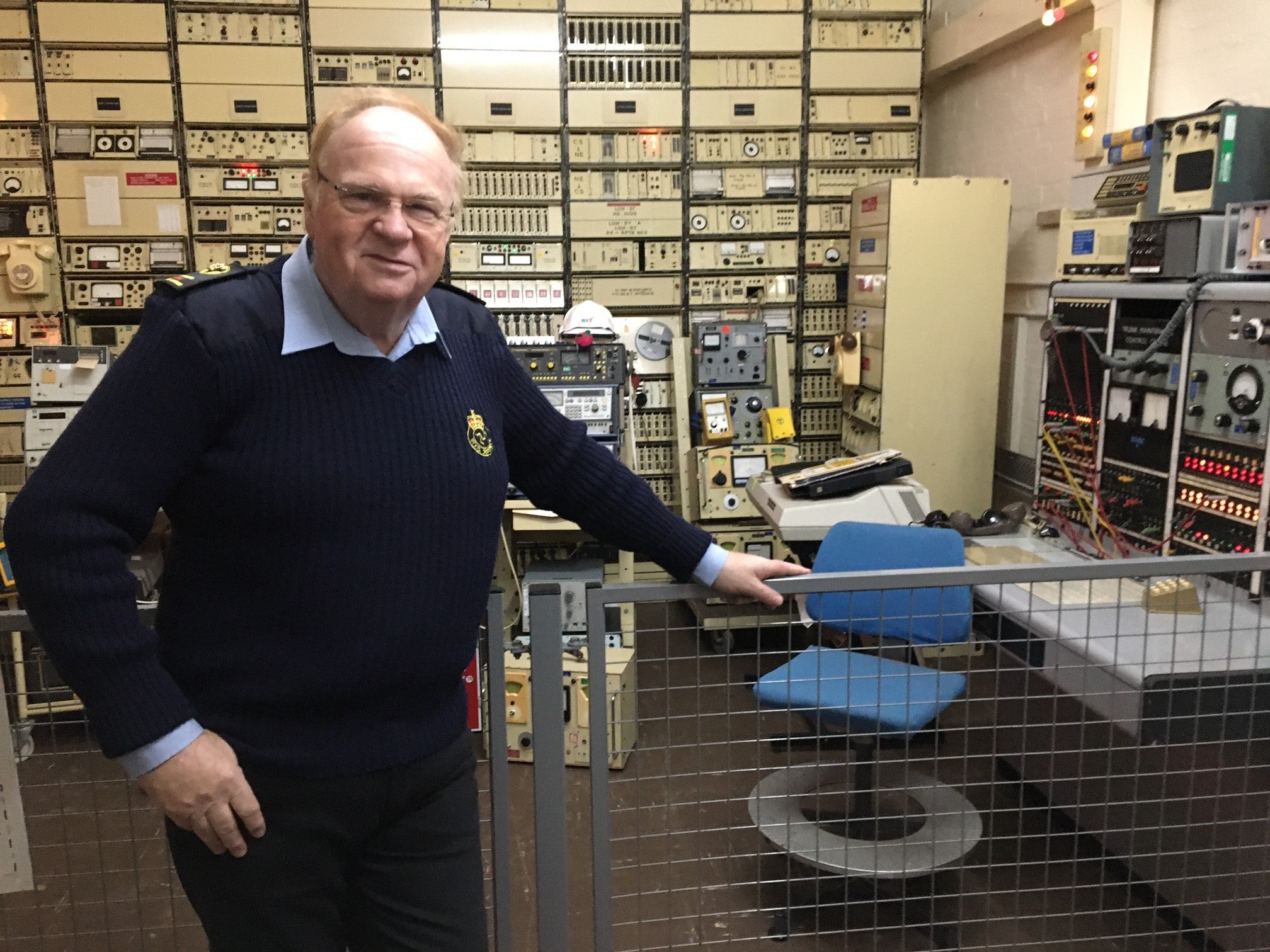

“It’s self-evident that, in the event of a nuclear strike, millions of people would have died,” says Rod Siebert, the one-time financial worker who bought the facility and turned it into a visitor attraction after it was decommissioned in 1992.

“But there would also have been survivors too. So, places like Hack Green were about trying to ensure that, for them, there was help and a way to rebuild the country.”

Visiting today, the whole place – constructed on an old RAF base in 1984 – feels like a relic from another more dangerous age.

Or, rather, it perhaps did until three weeks ago.

Now, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Vladimir Putin’s coded threats of a nuclear strike on any country that intervenes, there are growing concerns that the UK has allowed itself to become ill-prepared for such a potential attack.

Experts and government officials are being forced to wrestle with a question that would have seemed unthinkable just last month: does this country need a new nuclear resilience infrastructure?

“There is certainly an emerging argument that we have relied on deterrence for so long that we haven't given enough thought as to how we might withstand a nuclear attack,” says Dr Patricia Lewis, lead on the international security programme at Chatham House.

“And it may be we do now see a shift [in that thinking] as a result of current events.”

At the height of the Cold War, Hack Green – which cost £32m to construct – was just one of an integrated network of such bunkers stretching across the UK.

Some, like Kelvedon Hatch in Essex, were vast enough to accommodate 600 people. Others were one-man affairs, monitoring posts at which a volunteer would have tracked radiation fallout.

Crucially, these underground bases were just one aspect of a larger strategy to create some element of resilience in case of a devastating attack.

Alongside them, the Royal Observer Corp was a civil defence unit that would – if possible – have rolled into action in the event of a strike, while information films regularly alerted the public to what they should do (stay indoors and keep windows shut, basically).

Yet after the collapse of the Soviet Union, almost all of this was allowed to fall by the proverbial wayside.

The ROC was disbanded and information films became increasingly rare. While a handful are thought to remain – one is said to run under Whitehall – most were sold off. A couple became museums. One in Lincolnshire was bought by a data security company. Another in Somerset was transformed into a £1m eco-home.

The sheer cost of maintaining them was considered too expensive for a risk that seemed so low.

Yet, all the same, the Nineties downgrading of the nuclear threat has, analysts fear, now left the UK ill-equipped to deal with the consequences of a strike that would, yes, kill millions but also leave many survivors.

While no one is calling for a return to government bunker building – their effectiveness is considered questionable today – these relics are perhaps, nonetheless, symbolic of what some perceive to be a more general lack of civilian preparedness.

“This Russian invasion has happened and there are journalists going ‘there are no nuclear plans’ and that’s not quite true,” says Professor Lucy Easthope, co-founder of the After Disaster Network and an independent advisor to the government. “There’s more going on than people realise.

“Assuming it’s not an all-out catastrophe, there are arrangements for how to get healthcare to affected people, for radiation detection, body management, community recovery, all of that. You know, on a [small] scale, you saw it swing into action when [Alexander] Litvinenko was poisoned [with polonium].

“There were 47 sites that needed to be checked for radiation in London, and that was done, you know. The city carried on working. So these plans [exist].”

But, crucially, what’s missing, she says, is a wider community understanding of how to stay safe in the aftermath of an attack.

“We’re not generally aware at a civilian level of what we would need to do when the sirens go off,” says Easthope. “Certainly, no community preparedness like you saw in the Sixties and Seventies exists today.”

How would we get back to that level? Through school lessons on nuclear resilience, mandatory community drills, disaster manuals distributed to every household, and emergency boxes – generators, batteries, tea bags – stored in community buildings.

“That would be the Lucy dream,” says Easthope, whose book, When The Dust Settles comes out later this month.

Crucially, she argues, if the government did those things, the resulting knowledge instilled in people would be useful in a range of situations – from nuclear attacks to a simple power outage.

“That's why emergency planning is brilliant,” she says. “If you frame it right, your plans would be good for all sorts of scenarios…The specificities changed but the basics don’t.”

It is a point that Lewis also touches on. “There’s an argument we should already be having resilience training to prepare for climate change,” she says. “That would tick a lot of the same boxes.”

Back at Hack Green, Siebert also supports the idea. He went through similar training and drills as a volunteer with the ROC in the Seventies and Eighties.

“What a tragedy,” he says, “that we’re having these conversations again.”