Notre Dame has gone through a lot in its 856 years. It has endured ill-advised remodelling, revolutionary ransacking and pollution-induced decay. Hitler once had it slated for demolition.

On Monday, fire raged through the cathedral, causing its central spire to collapse. The full scale of the “colossal damage” has yet to be assessed, but French president Emmanuel Macron vowed the Paris landmark would be rebuilt.

“Notre Dame of Paris is our history,” Mr Macron said. “The epicentre of our lives. It’s the many books, the paintings, those that belong to all French men and French women, even those who’ve never come.”

France has rebuilt it before. In the early 1800s, Notre Dame was half-ruined when a writer used the crumbling structure as the setting for one of his greatest works, setting in motion a rescue operation nearly as a grand as its original construction.

“Parisians have had a direct relationship with their cathedral,” said Stephen Murray, an art historian and professor emeritus at Columbia University. “And I think it was largely because of the wave of interest because of the book.”

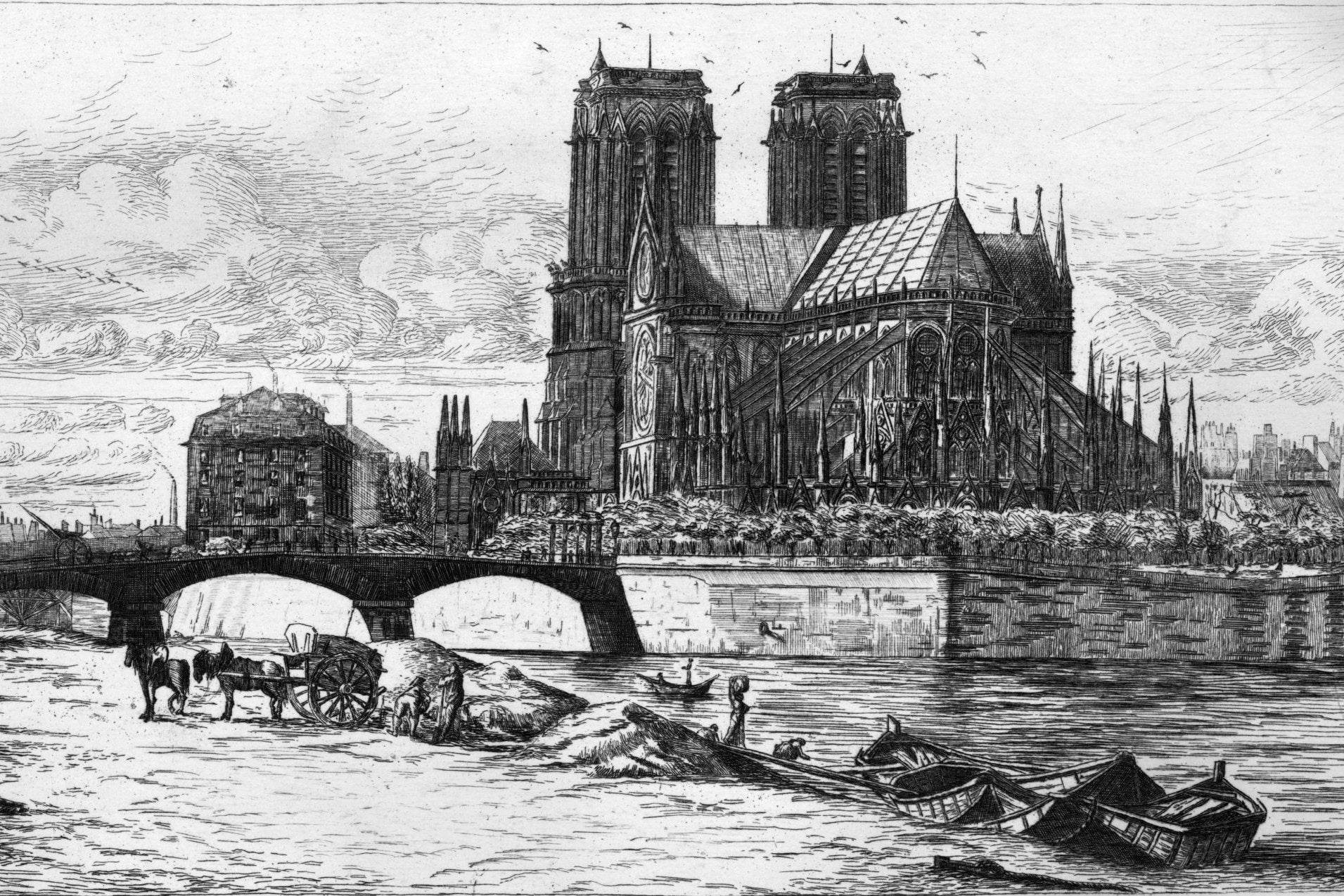

The first stone of the cathedral was laid in 1163 in the presence of Pope Alexander III, according to the Notre Dame website. The altar was finished about 20 years later; the two towers were constructed between 1225 and 1250, and the entire cathedral was completed in 1345.

During the reign of Louis XIV (1643-1715), Notre Dame underwent a rather unfortunate renovation. Stained glass was replaced with clear windows, a pillar was demolished to allow carriages to pass through, and the original rood screen – an ornate partition usually made of wood or stone that divides the nave from the chancel – was torn down.

The French Revolution era was even worse for it. Seized by revolutionaries, dozens of statues were destroyed. The bishop’s palace was burnt to the ground and never rebuilt. The spire was deconstructed after it was damaged by wind. Lead from the roof was used for bullets, and bronze bells were melted down for cannon, according to National Geographic.

The cathedral was returned to the Catholic Church by 1802, but it continued to decay.

Then, in 1831, the writer Victor Hugo published his novel The Hunchback of Notre Dame. It tells the tale of Quasimodo, the deformed bell ringer of the cathedral, who becomes obsessed with the beautiful Esmeralda.

But beyond the star-crossed lovers, Notre Dame is the star of the show. Hugo wrote two chapters just describing it. And he notably set his novel in the 1400s, at the height of Notre Dame’s heyday. Hugo wrote: “[I]t is difficult not to sigh, not to wax indignant, before the numberless degradations and mutilations which time and men have both caused the venerable monument to suffer.”

A classic novel now – more than a dozen movies have been based on it – it was also a hit when it was released. Suddenly, people cared again about the eyesore on an island in the middle of Paris.

The government formed the Commission on Historical Monuments, and in 1841 assigned architects Eugène Viollet-le-Duc and Jean-Baptiste Lassus to return Notre Dame to its former glory. Lassus died in 1857, leaving Viollet-le-Duc to finish the job.

“Viollet-le-Duc must have lived and breathed that building,” Murray, the historian said.

Over the next few decades, he oversaw the rebuilding of the spire, resurfacing of the stonework, restitution of the statues, construction of a new sacristy, reglazing of stained-glass windows, the addition of its famous gargoyles, construction of a new organ and countless other tasks. It was rededicated on 31 May 1864 by the archbishop of Paris.

“My sense of amazement ... is with all the vicissitudes that France [wa]s going through – with the 1848 revolution, with Napoleon III becoming emperor – somehow they just kept going with this restoration with a kind of unanimity and fixed purpose” that you don’t see today, Murray said.

Restoration projects have continued through the years. In fact, another one had just begun this month, funded in large part by the Friends of Notre Dame of Paris foundation, of which Murray is a member. He said he and other members were “in grief” Monday.

“In the Middle Ages you would’ve believed that God sent the fire because God wanted a better cathedral. But you can’t hope for a better cathedral at this point,” he said. “The question is how on earth are we going to find the resources to rebuild this one?”

© Washington Post