The use of nitrogen gas is considered too barbaric and inhumane for euthanizing dogs and cats, according to veterinarians, and has been banned in all but two states.

But, on March 18, Louisiana – after a decade-and-a-half death penalty moratorium – is set to execute a person this way.

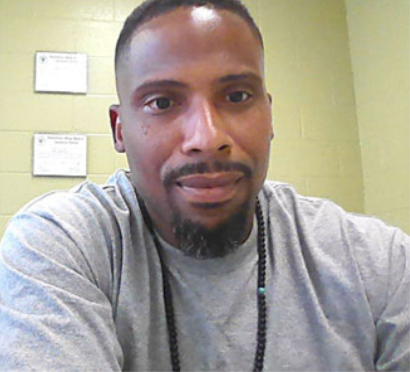

Jessie Hoffman has spent the better part of three decades behind bars at the Louisiana State Penitentiary, a maximum-security prison in the remote town of Angola. Now 46, Hoffman was sentenced to death following his 1998 conviction on a first-degree murder charge.

A jury found Hoffman guilty of kidnapping, robbing, raping, and fatally shooting 28-year-old New Orleans advertising exec Mary Elliot, whose body was discovered on Thanksgiving Day near the Middle Pearl River. Hoffman ultimately confessed to the killing, and DNA evidence linked him to the crime scene, according to prosecutors. While Hoffman’s defense team did not dispute the fact that he had shot Elliot, they argued in court that the gun went off accidentally during a struggle over the weapon.

Attorney Cecelia Kappel, executive director of the Capital Appeals Project and the Loyola University Center for Social Justice, is challenging Louisiana’s execution protocol on behalf of Hoffman. Louisiana paused executions due to broad political pushback on top of an inability to procure lethal injection drugs. Last year, Alabama carried out the nation’s first-ever execution using nitrogen gas, and has since put a total of four people to death using the method, which saw each of the condemned gasping, thrashing and convulsing for up to 20 minutes as they were slowly suffocated.

Hoffman, according to Kappel, “experienced torture as a child, and now the state wants to torture him to death.”

“They know what [nitrogen gas] does to animals, we shouldn't be doing that to human beings,” Kappel told The Independent. “This is a state that hasn't executed anybody in 15 years, and suddenly there’s this rush to kill. And with that rush comes a brand new, untested, execution method.”

Louisiana Governor Jeff Landry, a Trump-endorsed Republican who last year forced the state’s public schools to display the Ten Commandments in all classrooms, announced the new gassing protocol on February 10. Execution by nitrogen hypoxia, the technical term for the method, is carried out by placing a mask over the condemned’s face and replacing the flow of oxygen with pure nitrogen gas “for a sufficient time period necessary to cause the death of the inmate,” according to a summary of the protocol issued by the governor’s office.

“For too long, Louisiana has failed to uphold the promises made to victims of our State’s most violent crimes; but that failure of leadership by previous administrations is over,” Landry said in a statement at the time. “The time for broken promises has ended; we will carry out these sentences and justice will be dispensed... I anticipate the national press will embellish on the feelings and interests of the violent death row murderers, we will continue to advocate for the innocent victims and the loved ones left behind.”

The decision was, in Kappel’s words, “incredibly arbitrary,” and she said Landry and Louisiana Attorney General Liz Murrill are barreling forward with Hoffman’s execution without hearing from opponents. The Independent has reached out to Landry’s office for comment.

If the two were truly concerned with upholding the law, as they have stated, then they should “have no problem allowing this new execution protocol to be reviewed in the courts,” Kappel said.

Instead, they have thus far prevented it from happening. Kappel believes their insistence on using nitrogen gas is “politically motivated,” and asks, “Why now, why this moment, and why the rush? Why is the state in such a hurry to roll out this new protocol and use Jessie Hoffman as the test case?”

Kappel went on, “We have never had a court rule on the merits as to whether Louisiana’s [planned] method of execution is cruel and unusual. And that’s all we’re asking for… I think there is a small minority of people in this state who say, ‘Hang ‘em all,’ but they don't speak for the vast majority of Louisianans.”

.jpeg)

Hoffman himself is no longer the same person he was when he was arrested at the age of 18, according to his supporters. Since entering prison, Hoffman has co-founded a prayer group for fellow inmates, works as a mentor to younger men incarcerated at Angola, and has expressed profound remorse for his actions, advocates contend.

These qualities “really set him apart from a lot of other people on death row,” Kappel argued. “I represent people on death row, and he’s really a unique person.”

She said Hoffman “is beloved by both his fellow inmates and the prison staff,” a sentiment that emerges in messages of support released by Hoffman’s legal team.

“Jessie was very respectful of me and the other guards,” one former correctional officer at Angola said in a statement on Hoffman’s behalf. “He is also very thoughtful and understanding of other people. He would share food with other inmates and help stretch the phone into a cell so the other guys could talk to their families. I think Jessie deserves a chance.”

Kappel is concerned not only for Hoffman, but also for those who will watch him die, including prison staff, the media, and members of the victim’s family, she told The Independent.

“Nobody wants to witness a death happening in that horrible, gruesome way,” Kappel said.

Hoffman is scheduled to be executed on March 18.