Osgood “Oz” Perkins has scrupulously honed a directorial style like no other. With films like The Blackcoat’s Daughter, I Am the Pretty Thing That Lives in the House, and Gretel & Hansel, his dreary and lurching vibe is unmistakable. But while he makes stunningly photographed thrillers, his narratives tend to linger at a pace that’s more tortoise than hare. For some, it’s the pinnacle of slow-burn suspense. For others, like myself, it’s been an uphill battle.

Longlegs perfects the filmmaker’s formula by leaning into Perkins’ dawdling aesthetics that creep like rolling fog, emphasizing continuous hunt-and-stalk tension pulled tight like a hangman’s noose. Perkins’ command over persistently low-gear speeds has never been better, nor has his presentation been more stupendously infernal. Longlegs is his best work by a country mile, and comes emphatically recommended whether you’re a devoted fan or a first-time appreciator (like me).

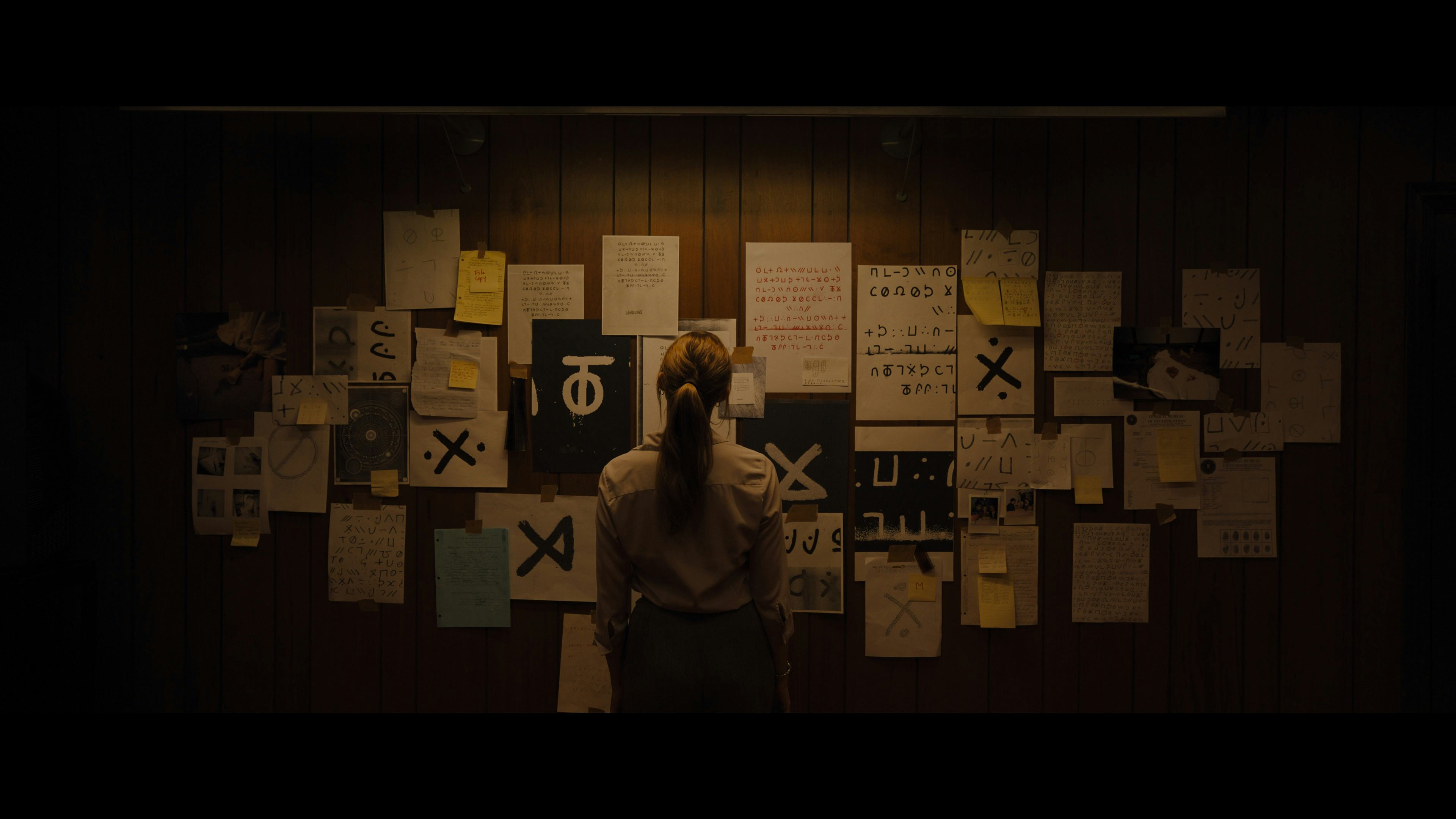

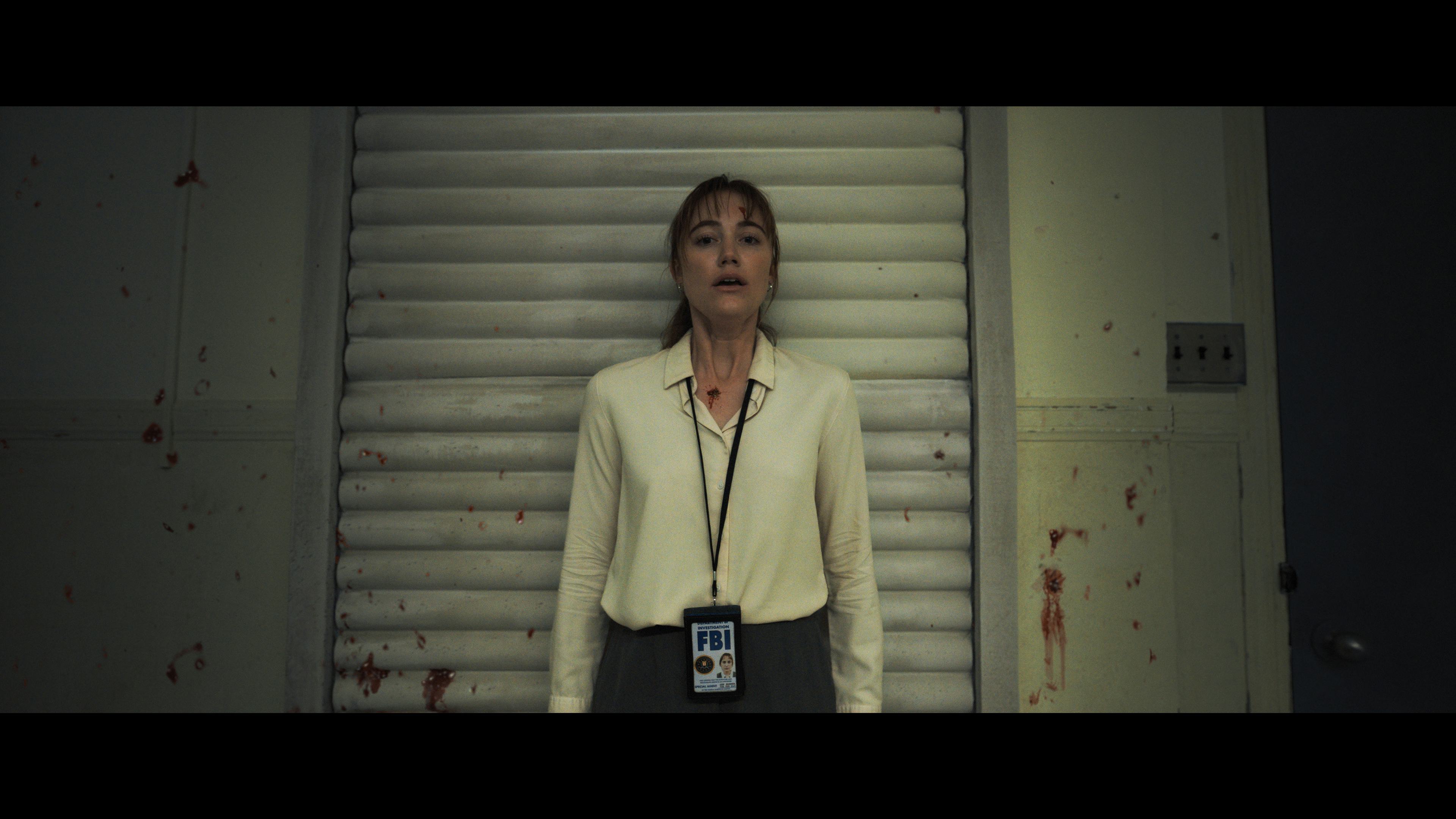

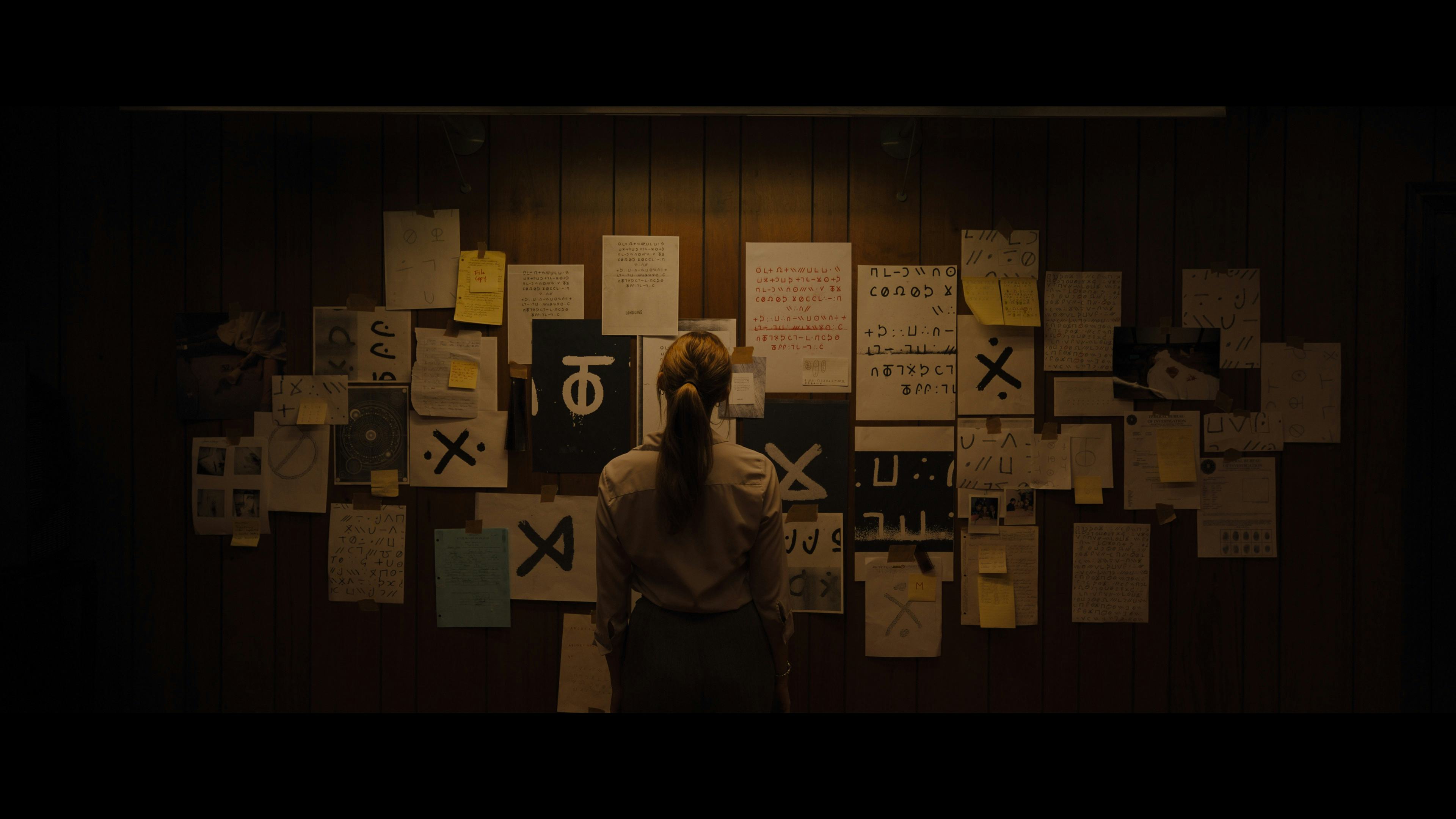

Maika Monroe stars as FBI recruit Lee Harker, cementing her status as a powerhouse contemporary genre star (It Follows, The Guest, Villains). Harker finds herself in the Pacific West investigating an unsolved serial killer case, teaming with her superior, Agent Carter (Blair Underwood). We know Harker’s adversary as “Longlegs” (Nicolas Cage), a disturbed individual responsible for the deaths of innocent husbands, wives, and children. It’s all very procedural as Harker deciphers Longlegs’ alien language and cracks occult puzzles, with respects paid to Seven or Silence of the Lambs. But Longlegs becomes a putrid, twisted, and triumphantly bleak satanic thriller hand-delivered by Lucifer himself, felt through Harker’s desperate actions to end Longlegs’ massacre streak.

Perkins has built a brand on drifting camera movements and acidic themes, torturous techniques that elevate the blasphemous brutality of Longlegs. Every scene is boiling over with unease and discomfort, like evil can strike at any second. There’s something perversely voyeuristic about Harker’s investigation and the way cinematographer Andrés Arochi frames Monroe when she’s alone, as the camera peers through windows or from behind. Malevolence flows like a river through each scene, drawing comparisons to equally delicious voyages into the devil’s den like Pyewacket or The Devil’s Candy. Longlegs is Perkins’ trademark aesthetic at max volume, lingering in your thoughts, under your skin, and in the pit of your stomach well after it’s over.

Longlegs dances a fine line between police thriller and hellish horror tale, never losing the intrigue of blending both formulas. Perkins purposely uses clashing red and black color filters to stir madness, overtop icky inserts of slithering serpents that act as transitions between scenes featuring Harker and Longlegs. Prominent ’70s rock ‘n’ roll acts like T. Rex play into Longlegs’ uncanny behaviors, tying earworms like “Bang a Gong (Get It On)” into heinous visions. Perkins leans on eerie imagery like dead-eyed dollies, intertwined reptilians, and crime scene evidence that hits like a hundred-pound hammer. Longlegs doesn’t spare its audience from nauseating shots of maggots writhing atop corpses or people getting their brains splattered onto windows; psychological scars and painful punishments are the film’s parting gifts.

Monroe and Cage are a dynamite cat-and-mouse duo whose performances are intensified by the mile-high flames of thematic ruination. Monroe’s performance is wounded enough that we fear for her safety but resilient enough that we can’t wait to see how she figures out another puzzle or confronts demons from her childhood. Her eyes tell stories, whether that’s selling out her rattled nerves or pleading for mercy, while her professional coldness plays humorously robotic against Underwood’s pleasantries or his daughter’s adorable banter. Monroe is a generous screen partner who contrasts her co-stars’ personalities, especially against Alicia Witt’s portrayal as Harken’s prayer-pushing and worrisome mother.

Conversely, Cage is evil incarnate: a bloated, pale-faced David Lee Roth carny knockoff who is inescapably terrifying to behold. This is the scariest Nicolas Cage has ever been: like Tiny Tim meets ’70s hair metal with a healthy dash of To Catch a Predator. No matter what Cage does on screen, he’s breathing fire and brimstone. His scratchy but mousy speaking voice is obliterated when he then screeches like a delirious frontman, and his smiley-psycho physicality pulls from socially awkward tics that raise your hairs upon sight. Perkins brings the best out of Cage, a frightening America’s Most Wanted monster and hideous cultlike charmer.

That all said, given my prior comments about Perkins’ work, the film’s momentum dips once or twice — but that’s splitting hairs for criticism’s sake. Pristine “lingering” can feel more experimentally arthouse than functional in these scant moments, falling back into style over substance. Perkins’ movies proceed with tiptoe-light steps (intentionally), and that’s been one of my struggles over the years. Midsection sequences can unfold in a bit laxer manner than might be my preference, but it’s representative of what Perkins’ fans adore and better energized than usual.

All in all, Longlegs is diabolical. It’s a satanic powerhouse that drags the audience through hell and back. Its harsh, in-your-face violence is felt viscerally, its cinematography bathes in artful repugnance that’s organically horror-forward, and its influential odes to classic horror-thriller procedurals are sickeningly effective. Perkins’ latest doesn’t sacrifice the filmmaker’s calling cards but tempers his indulgences for a broader appeal. Longlegs makes Netflix’s serial killer obsession look like child’s play — this one’s a top-tier soul-crusher.