It looks like curtains for New Zealand’s Labour government.

The party won its best result since 1946 just three years ago, as voters rewarded Jacinda Ardern for keeping Covid-19 out and punished the opposition for its litany of scandals, giving Labour one of every two votes.

Now Ardern is gone and the political capital won at that election has been either spent or squandered, often on policies that aren’t likely to survive past Christmas if the government changes.

The Guardian’s new Essential poll put Labour’s support at just 29% – not much over half the 50% it won in 2020. And the support needed cannot be found elsewhere on the left: Labour packaged with the Green party’s 8.5% and Te Pāti Māori’s 2.5% still only win 52 seats, nine short of the 61 needed to govern.

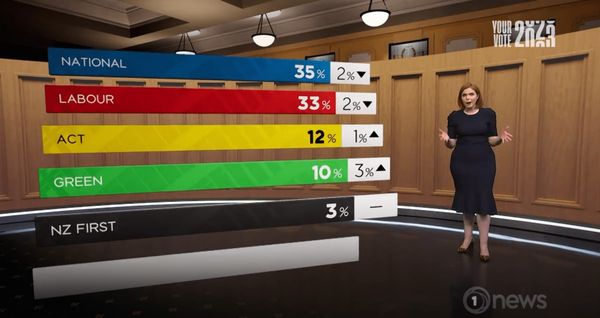

About one in 20 voters (6.2%) are still undecided, but the gap between left and right in this poll is so large that even if every single undecided voter chose Labour, the party would still lose October’s election. Other polls are not quite as dire for Labour, but still put the rightwing bloc of National and Act ahead.

It isn’t quite game over. Prime minister Chris Hipkins could pull off the campaign of his life in the next two months, exploiting the fact that the public don’t seem particularly enamoured with the opposition. Christopher Luxon, the former Air NZ CEO who leads the National party, still trails Hipkins on personal preference polls and has failed to consolidate support on the right, with a big chunk of conservative voters hitching their wagon to Act and NZ First instead.

Hipkins would need to do several complicated things at once to manage a win.

The first would be an effective scare campaign about what would be the most rightwing New Zealand government this century. National has little serious policy to target but its likely coalition partner Act support or have recently supported far more alienating positions like minimum wage cuts, the abolishment of assistance payments for new parents and winter energy payments for the retired, and the end of fees-free tertiary education. This would hardly be inspiring, but Scott Morrison’s win in Australia in 2019 showed that a strong enough negative campaign about the “unknown” of an opposition can turn around seemingly unwinnable elections.

The second would be to reframe the government as an oppositional force, as angry about the status quo as the public is. New Zealanders are rightly upset about their falling real incomes, with high food costs in our uncompetitive grocery sector, high rents in major cities, and high interest rates for those who bought houses while they were severely overvalued. In the UK, voters clearly blame the government for high interest rates, pointing to the effects of Liz Truss’ mini-budget. In New Zealand the government is not so squarely seen as the source of everyone’s economic pain, but it is hardly seen as the solution either, especially as it has been in power since 2017. Moves like removing GST on food – even if most experts see this as silly and inefficient – could be a bit of a circuit-breaker.

The third would be to reinvigorate his cabinet; Labour was far more competitive in this election a few months ago, before a series of scandals befell the government, including a transport minister who failed to sell shares in an airport and a justice minister who was charged with reckless driving and refusing to accompany a police officer. It is likely that the damage done by these scandals is irreversible, but if there is any chance of building public trust back it will need to be done with clear air.

There are just over 50 days until Kiwis start voting. If Hipkins managed such a turnaround he would be written into the history books as a political savant. If he doesn’t he will end up a footnote, a pub quiz question in 20 years – and Labour could face a very long road back to power.

Henry Cooke is a freelance journalist covering New Zealand politics