This week the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) announced intentions to regulate data brokers by making them comply with the Fair Credit Reporting Act. Under the proposed rule, data brokers would be limited in their ability to sell personal and financial information about American consumers, specifically income, credit history, credit scores or debt payments.

As reported by The Verge, the rule would cause data brokers to comply with the FCRA, much like credit bureaus and background check companies must, which would limit their ability to both obtain and use the information they obtain about consumers. Data brokers would be required to get clear consent for data sharing, essentially forcing them to get explicit permission to sell a consumer's sensitive personal financial information.

CFPB director Rohit Chopra directly referenced the massive National Public Data breach that occurred earlier this year and leaked more than 200 million Social Security numbers that were then offered for sale across the dark web. Chopra pointed out that threat actors don’t need to hack anything to get American’s most sensitive data because “data brokers – the outfits that collect and sell detailed information about our personal and financial lives – are making this data available to anyone willing to pay a price.”

The regulation proposed by the CFPB would target private companies, not government operations and a CFPB spokesperson said the agency is working on ensuring that government agencies still have appropriate access to the information they need to perform their jobs. The CFPB will be accepting comments on the proposed rule until March 3, 2025 though it is possible that the upcoming change in administration will alter the agency or its focus before this deadline.

What can you do to protect yourself and your data?

When it comes to data brokers and people finder services, the name of the game is going to be how much time you’re willing to spend or if you want to hire a service to handle part of it for you. Realistically, some of your information is going to be available somewhere for a price. Your goal is to reduce that as much as possible, and your options are to do that manually or to subscribe to a service to do that for you.

Public sources already share information like property records, court filings, voter registrations, and birth, marriage and death records. Though data brokers do pull information from social media, much of their data will come from public records - over which you have no control. This means that a realistic strategy is not to prevent data brokers from getting your information but to prevent them from keeping it.

Very few laws exist to restrict data brokers from buying or selling your information, and they usually apply very narrowly. California makes companies comply with requests to not post information about registered victims of domestic violence, stalking or sexual assault. The FTC has also recently banned certain data brokers (Mobilewalla and Gravy Analytics) from collecting and selling location tracking data linked to particular locations such as healthcare facilities, churches and schools for public safety reasons.

The Fair Credit Reporting Act already prohibits the use of information from data brokers for screening of potential employees, tenants or insurance clients but there isn’t such a thing as a registry to allow anyone out of data-broker tracking. You have to complete online forms or use snail mail (sometimes even fax) in order to be purged from their databases.

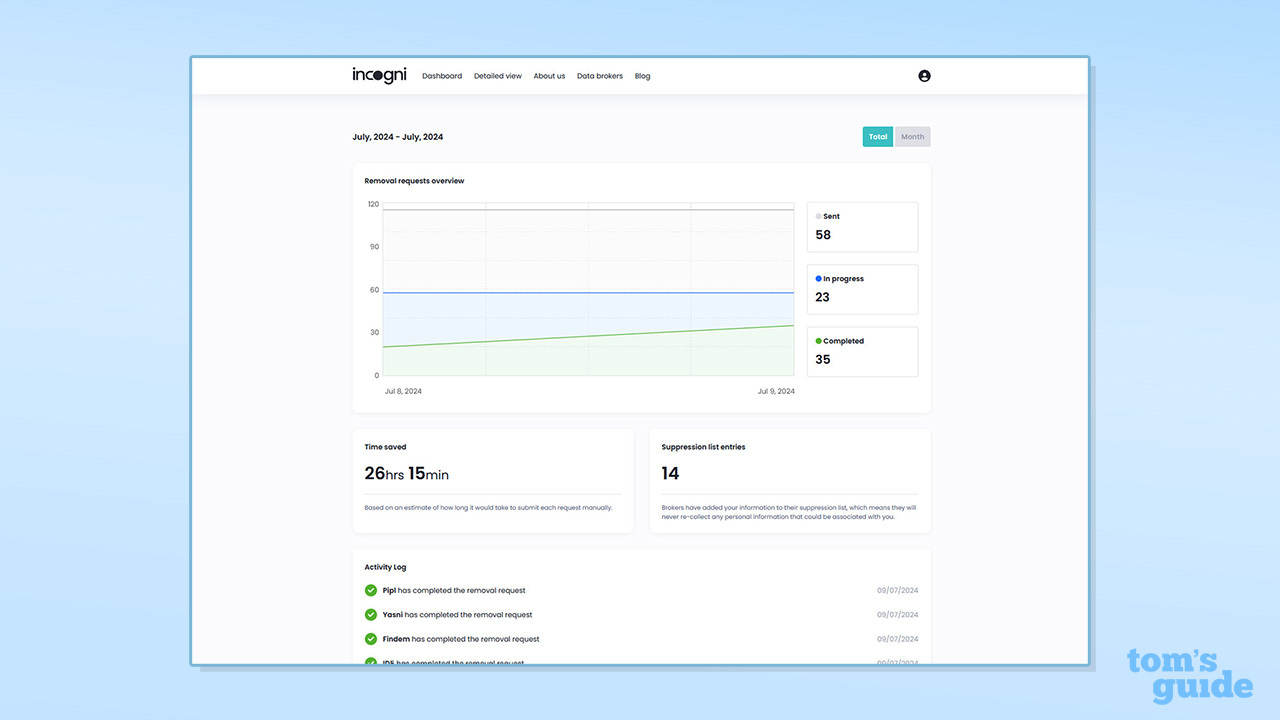

Some subscription based privacy services, like DeleteMe or Privacy Duck, will do this for you for an annual fee by submitting your information to dozens of data brokers at once – usually for a price equivalent to an Amazon Prime membership. However, there's also Icogni from the VPN provider Surfshark which we praised for its easy set up and regular reminders about the progress of its data removal in our review.

When we tried out this process, we acknowledged that there weren’t going to be perfect results. It was more about reducing the overall risks, and that some brokers would continue to collect new data or some opt-out processes would need to be run more than once. This makes the subscription model particularly appealing over the DIY approach, which can become incredibly time consuming.

To get started yourself, you'll want to begin by searching for your own name, phone number, email address and address to see what results come up. To be extra careful, a search with your name and the word "address" or your name and "phone number," isn't a bad idea either.

Then you can try to find your own information on data broker sites (like Spokeo, Intelius, Whitepages) to see what they have and how accurate it is for you. You can also Google yourself and do a Google image search to see what pops up. Think about what you've found, if you're comfortable with it being widely available and whether or not it might be worth signing up for a dedicated data removal service or trying to do the heavy lifting on your own.

Data brokers have had free reign of the personal data they've managed to collect on Americans for years now but if this new rule is passed, we could see their efforts curtailed significantly. In the meantime though, it's up to you to prevent even more of your personal information from ending up online (when possible).