Moffat Takadiwa is a Zimbabwean artist famous for creating work from found materials. His exhibition Vestiges of Colonialism, curated by Fadzai Muchemwa, opened at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe on 16 March. This is the 40-year-old Takadiwa’s first solo show in Zimbabwe in a decade. Having exhibited around the globe, he’s best known for his sculptures made from consumer waste and urban residues such as toothbrushes, computer keyboards and cheap perfume bottles.

As an art historian focusing on contemporary Zimbabwean art, I have been researching the artist’s work for the past few years. With stunning, large scale sculptural works and installations, this exhibition unveils a map of the artist’s mind and reveals a profound and innovative space brimming with music, plants, soil, time and everyday life.

Vestiges of Colonialism is not only a landmark show, but also a timely conversation on colonial legacies in Zimbabwe. By engaging with the works, one discovers subtle vestiges of colonial constructions that are knitted into the fabric of Zimbabwean society and continue to have an impact on people’s lives today.

Colonial hangover

Entering the gallery, a visitor’s eye is immediately drawn to magnificent sculptures mounted on a two-storey wall. Made from toothbrush heads and computer keys, this sculpture series, Korekore Handwriting, is the artist’s acknowledgement of the people who shape his practice. Belonging to the Korekore people of Zimbabwe’s broader Shona ethnic cluster, Takadiwa’s practices are heavily influenced by the community’s weaving culture and collective means of labour.

Placed on the centre of the ground floor is an installation titled Walk of Shame that contains thousands of toothbrush handles. Before being arranged by hue and framed in a large wooden square, they were literally residues piled up in front of Takadiwa’s studio at Mbare Art Space. To access the studio, one had to navigate this path of handles, taking care not to trip and fall. Over time, they have accumulated memories and histories of many people who have trodden on them, as evidenced by the soil, dirt and odour affixed to them. Drawing from the Hollywood Walk of Fame, the artist examines the path one might take to get ahead while grappling with residues of colonialism and global commerce.

These pieces demonstrate the materiality of Takadiwa’s work. He has been working with consumer waste since the late 2000s when a movement to redefine art materials emerged in Harare during the country’s socio-economic crisis. With years of experimenting, Takadiwa has developed his own visual language and mode of working with these everyday items. Residues are no longer merely art materials to him but a metaphor for post-colonial conditions, what he terms a colonial hangover. Most of his sculptural work involves a process of deconstruction and reconstruction of the materials by many hands. It is a gesture towards and a question about the possibilities of transformation through collective work.

A question of land

The gallery’s ramp leads visitors to a distinct yet related space, which they must not only observe, but also experience. A work titled Rugare Kwamuri presents a floating garden along the corridor, with rugare vegetables grown in burnt furniture drawers of the type used by the colonial administration hanging under the dome lights. Rugare is a loaded word in local lingo that literally translates to peace or good life. It is the Shona term for a common variety of kale that can be found in ordinary households.

Farmers in the northern region of South Africa refer to the vegetable as “muRhodesia”, indicating its historical association with the colonial state of Rhodesia, renamed Zimbabwe. Rugare is also the name of an old township in Harare. It was constructed by Rhodesia Railways to house its native workers, separated from the white settlers. The colonial legacy of a poor built environment – houses, roads, medical and educational infrastructures – has barely changed today.

Rugare also reveals an affinity with land. As the vegetable grows to reach massive sizes, its height indicates the length of time a household has resided in a dwelling, a symbol of a stable life. Yet, as pointed out by one audience member, to start with, one must have the access to land for growing them.

Along with rugare, roses were also planted by the artist in Mbare, the oldest township in Harare, and then displaced to the gallery space. With rose cuttings flourishing in small medical containers on burnt colonial office desks, the installation Maruva Enyika touches on the colonial history of Rhodesia as a rose plantation that provided decorations for the British Empire.

Still transforming

At the opening, one speaker, a board member of the gallery, ironically apologised for and downplayed the exhibition theme of colonialism, presumably to show off his hospitality to visitors from former colonial countries. His peculiar statement demonstrates the challenge as well as the necessity to have the discussion in this post-colony.

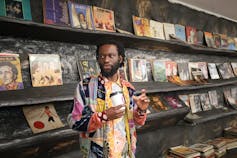

This exhibition, thus, is a timely conversation. To demonstrate the tension within art institutions, the artist pointed to the work Mudiwa’s Kitchen. It’s an installation of vinyl music records displayed in a traditional kitchen setting. Found in Harare, the vinyls are predominantly old-fashioned and western. By naming the work after his daughter Mudiwa and constructing a domestic scene in an art institution, it poses a bold statement to challenge and reimagine oneself in the still-transforming postcolonial institution space.

Same Old Songs also examines these vestiges of colonialism. Using old vinyl records and cassette tapes, the installation is monumental. Polyester magnetic tape hanging from the ceiling creates a time jungle, inviting audiences to listen to histories – not with ears, but their bodies and movements.

Upon people entering, it turns into a performative piece. Some visitors quickly cross pathways, some get trapped, some touch and observe to search the traces of the past. The artist becomes the audience, watching the work being (re)completed by the participants.

A series of wall-hung sculptures, Colonial Product, links these installations with Sando Dzako (Big Up) in which hundreds of nails are hammered into a dismantled and burnt colonial dining table. It suggests it’s time to have a conversation over colonial presence. Or, as Muchemwa said in her opening night speech:

How we can break things, to unburden meanings, to play around and find solutions. To open spaces in the meanings, spaces in which we can inject ourselves so that we can get rid of these remains.

The exhibition is on until 8 May

Lifang Zhang is a PhD candidate in Art History and a member of Arts of Africa and Global Souths research programme at Rhodes University. Her PhD research is partly funded by NRF and Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.