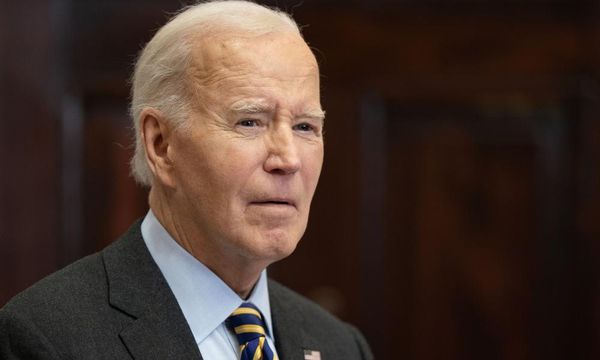

Sir John Gieve

Ministers may struggle to “hold the line” in their refusal to back higher pay deals for hundreds of thousands of public sector workers, a former Bank of England chief said on Wednesday.

Sir John Gieve, the bank’s former deputy governor for financial stability, also largely rejected the Government’s argument that bigger pay rises for nurses, ambulance crews and other public sector workers would significantly push up inflation.

He stressed the key issue was instead how they could be funded given the “formidable squeeze” already on public services’ finances, so bigger pay rises would probably have to be funded by higher taxes or more borrowing.

However, Sir John believes that ministers may eventually have to give in to some of the unions’ demands.

“It’s quite doubtful whether the Government can hold the line on public service pay,” he told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme.

The veteran economic expert and former top civil servant added: “We have seen this before on previous occasions when the Government has tried to hold down public sector pay to avoid having to put up taxes and borrowing and in order to set an example to the rest of the economy and it depends what people are prepared to put up with.

“And at the moment there are signs that public service workers are saying ‘no, we have had enough’.”

Official figures on Tuesday showed wages in the private sector rising by nearly seven per cent on average, and under three per cent for public sector workers.

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt defended the Government’s stance on the industrial disputes as the latest data showed inflation dropped slightly to 10.7 per cent in November, down from 11.1 per cent the previous month.

He said: “It is vital that we take the tough decisions needed to tackle inflation - the number one enemy that makes everyone poorer.

“If we make the wrong choices now, high prices will persist and prolong the pain for millions.”

However, Sir John challenged the idea that public sector wages were a key cause of inflation which was being driven “largely” by the high energy prices caused by Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine and the Covid pandemic and its aftermath pushing up the cost of imported materials.

“The public sector pay increases don’t directly affect prices, on the whole we don’t pay for our health service or police service through prices,” he said.

“So it does not have a direct effect on inflation.”

He added higher public sector pay may influence inflation “indirectly” by forcing private sector companies to pay more for labour but he does not believe that this is a “major effect”.

But he stressed that “paying for” increases in public sector wages was the “key point”.

Most public spending programmes were set a year ago, he added, on a cash basis with inflation “topping out” at about four per cent at Easter.

“Here it is at 11 per cent,” he explained.

“There is a formidable squeeze going on in the public sector.

“If wages go up by more then that will squeeze it further and the Government will have I suspect to find extra money for the public services if public service wages go up by more than they have allowed for.”

So taxes or borrowing may have to go up.

No10 has shied away from telling private sector companies to limit pay rises despite taking a tough line on the lower public sector wage increases.

Polling suggests support for the strikes remains reasonably strong, though it may be falling slightly, especially backing for the rail workers walk-out over Christmas.

Hopes are rising that inflation may have peaked.

But Harriett Baldwin, Tory chair of the Treasury Committee, added: “There are still a lot of risks in terms of inflation in the economy and obviously it’s the job of the Bank of England to get inflation back down to the target range that the Chancellor has asked him to achieve.

“A lot of the price pressure we are seeing came from Putin’s evil invasion of Ukraine and weaponizing the cost of energy against western economies and it does look as though some of that pressure has passed.

“I think what the Bank of England tells us they are concerned about is the potential for that to feed through into a further round of wage inflation, for people’s inflation expectations in the UK to change so that it becomes much more embedded in expectations and in discussion with employers about pay and then feeds through further into higher rates of inflation.”