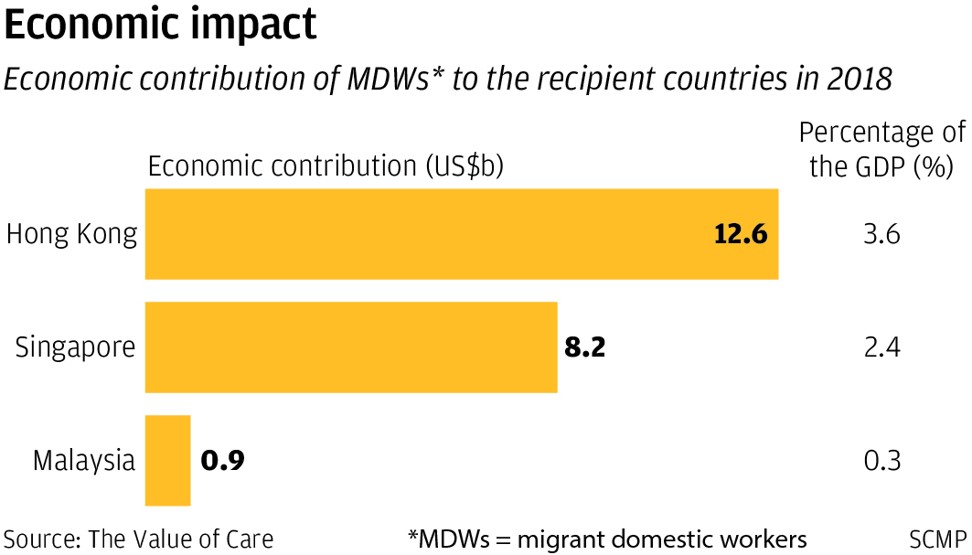

Hong Kong’s migrant domestic workers last year contributed an estimated US$12.6 billion to the city’s economy, representing 3.6 per cent of the city’s gross domestic product (GDP), according to a report released on Wednesday.

These domestic workers also enabled more than 110,000 mothers in Hong Kong to rejoin the workforce. Elsewhere in Asia, foreign domestic workers contributed US$8.2 billion to Singapore’s economy (2.4 per cent of GDP) and US$900 million to Malaysia’s (0.3 per cent of GDP).

“Domestic work and caring for others is in many ways invisible work, behind closed doors. This is a hidden side of the economy and now we can put a number for the first time on the huge value of their care,” said Lucinda Pike, executive director of Hong Kong-based charity Enrich, which promotes the economic empowerment of migrant domestic workers.

FILLING THE CARE GAP

The report, “The Value of Care: Key Contributions of Migrant Domestic Workers to Economic Growth and Family Well-being in Asia”, was commissioned by Experian, a global information services company, in partnership with Enrich. It examined for the first time the economic contribution of migrant domestic workers in Asia.

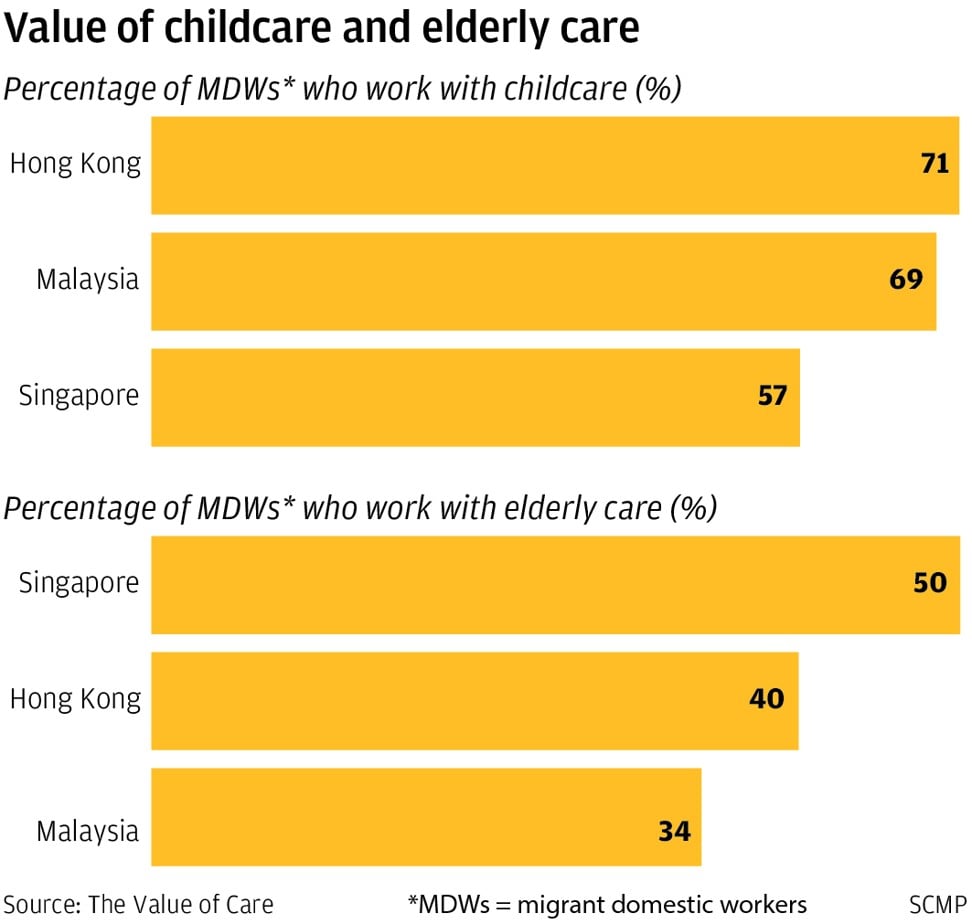

More than 21 million migrant domestic workers fill the care gap in Asia and the Pacific. Experts predict the demand for paid domestic work will continue to rise as populations age rapidly, fertility rates remain low and the shortage of affordable care services persists in many countries.

According to the report, employing a migrant domestic worker for childcare in Hong Kong and Singapore is at least three times cheaper than alternatives such as childcare centres, kindergartens or private tutors.

“Perhaps this does show greater care infrastructure is necessary in order to support families, especially those with children and elderly [relatives]. But the reality is that migrant domestic workers do help to fill this care gap,” Pike said. “[As a result], many women are able to enter the workforce because of other women taking these jobs.”

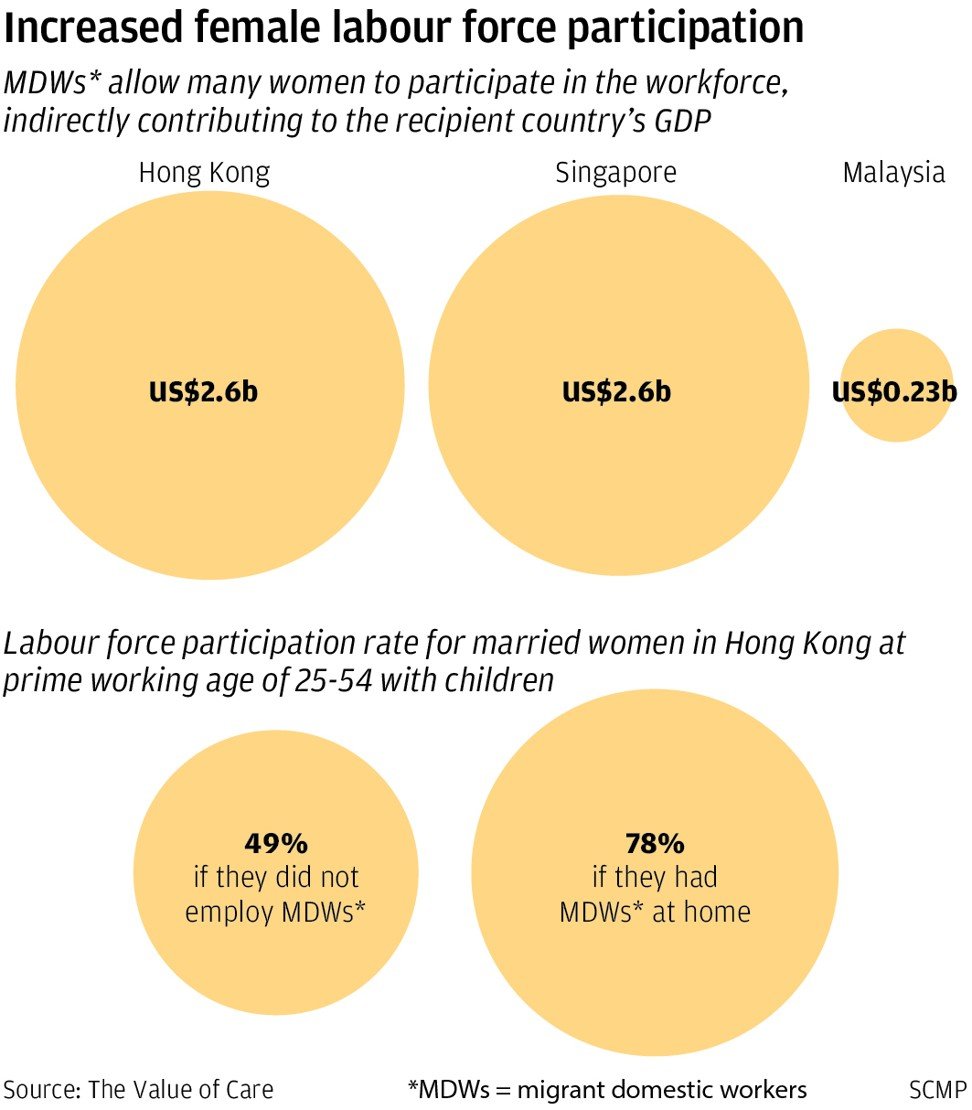

The research shows that, in Hong Kong, only 49 per cent of mothers aged 25 to 54 would be able to work if they did not employ a foreign domestic worker. Due to employment of migrant domestic workers, this labour force participation increases to 78 per cent.

As a result of other women being able to work, these workers not only contribute to family well-being in the countries where they are employed, they also indirectly add US$2.6 billion to Hong Kong’s economy, US$2.6 billion to Singapore’s and US$230 million to Malaysia’s.

FINANCIALLY EXCLUDED

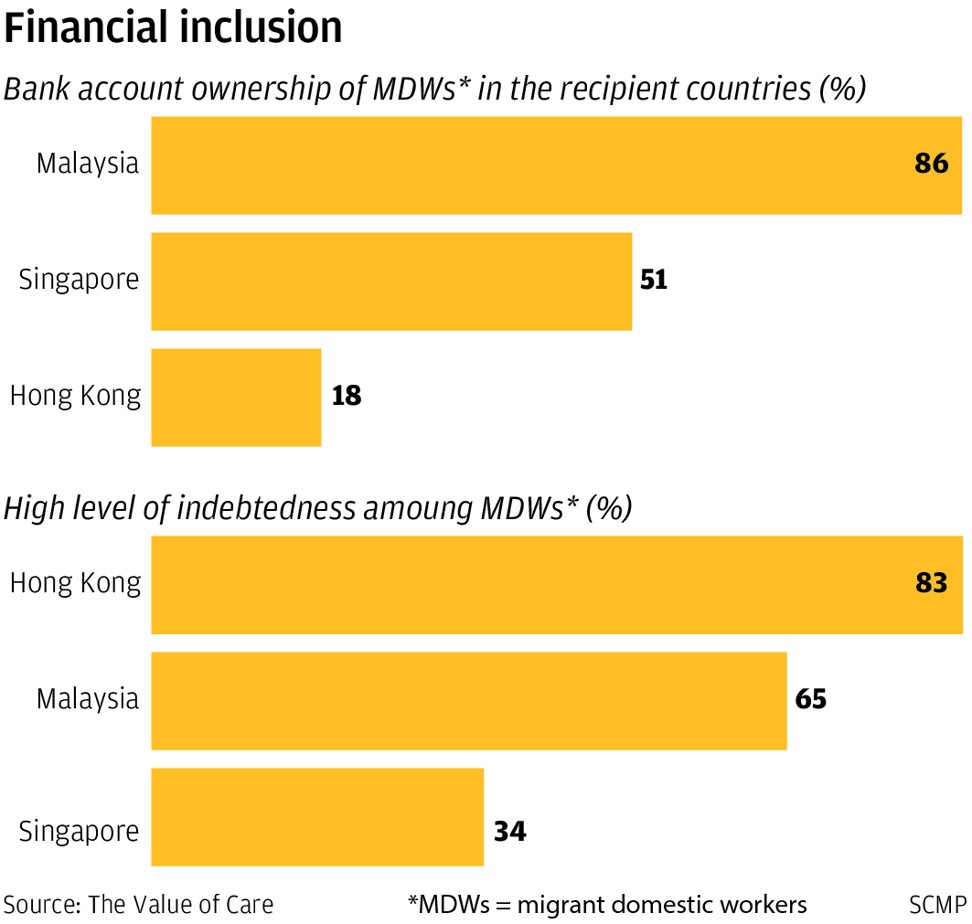

Despite the contribution made by these migrant domestic workers, the report paints a bleak picture of their lack of access to the local economies in some of the countries where they are employed. For example, only 18 per cent have bank accounts in Hong Kong, although this number rises to 51 per cent in Singapore and 86 per cent in Malaysia.

“It’s worth noting that the highest economic contribution is to Hong Kong but the lowest level of financial inclusion is also found in Hong Kong out of the whole region,” Pike said.

They are not only more financially excluded in Hong Kong – they are also more likely to be in debt, and many return home financially worse off than when they arrived.

In Singapore, about 34 per cent of domestic workers reported being in debt. In Malaysia, it was 65 per cent. In Hong Kong, the figure increased further to 83 per cent.

According to the study, a lack of financial literacy, strict regulations for opening bank accounts and a lack of funds are among the factors contributing to this economic exclusion.

“About 74 per cent of domestic workers in Hong Kong said that they don’t need a bank account – this is partly due to lack of financial literacy,” Pike said.

“These results also show that the barriers in Hong Kong to access financial services are much greater than, for instance, in Singapore, where the government is trying to change regulations, mandating employers to pay through bank accounts, and also encouraging more banks to offer no minimum amounts [in order to open an account].”

She also said that if domestic workers don’t have access to legitimate financial institutions, “they are more likely to seek loans from unlicensed money lenders, who charge much higher interest rates”.

EDUCATION AND EMPOWERMENT

According to Pike, financial inclusion goes hand in hand with education.

“We think that when you educate a woman, you educate a village,” she said. “Offering financial and empowerment education, which we struggle to find funding for, is the top priority for us … But it’s also important to provide other educational opportunities.

“This is not just for the Filipino or Indonesian governments to deal with. It also affects the financial growth of Hong Kong, so we really want to have an open conversation about this issue.”

Pike pointed to an increasing regional competition to attract workers, as countries such as Japan have recently adopted more flexible regulations for migrant domestic workers.

“We really believe that is important for cities like Hong Kong and Singapore to recognise that domestic workers have a positive impact in their cities and that there are steps that can be taken to make sure they are also protected, especially given that their economic contribution is only going to grow,” Pike said.

In Hong Kong, the population of migrant domestic workers has steadily increased over the past years, reaching 385,000 in 2018. The Hong Kong government projects this will rise to 600,000 by 2047.

Singapore, where there are about 250,000 such workers, estimates it will need 300,000 in about a decade.

The research contained in the report was based on face-to-face interviews with 100 migrant domestic workers in each location: Singapore, Hong Kong and Malaysia. It also incorporated official data.

The calculation of these workers’ contribution to the regions’ GDP was made based on the cost of domestic work if paid at local rates, the value of their own personal spending in Hong Kong and the time of the people able to seek other employment as a result of foreign domestic workers performing their duties.