Melbourne’s Capitol Theatre – and the reinforced concrete and steel-beamed building around it – turns 100 today.

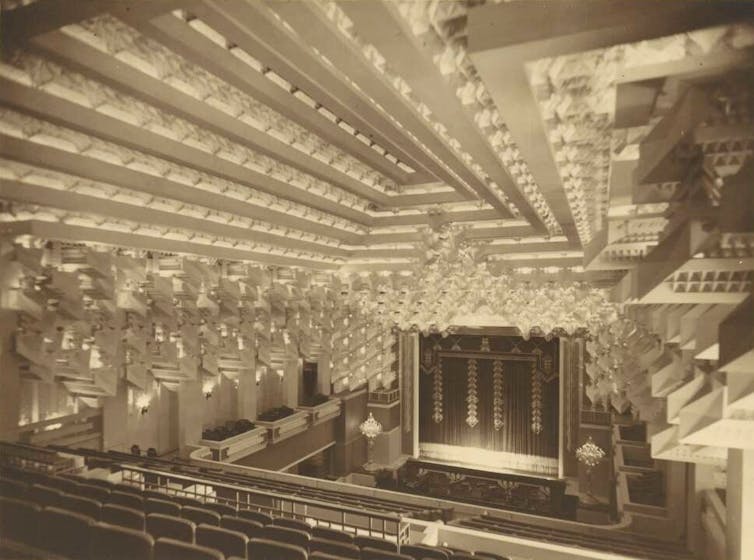

The spectacular modern architecture, which was refurbished some years ago by RMIT, was designed by US architect Walter Burley Griffin and his partner Marion Mahony Griffin. It opened on November 7 1924 as a grand “picture palace” and is still used today to host a variety of screenings and live performances.

The Capitol was once described by renowned Australian architect Robin Boyd (1919–71) as “the best cinema that has ever been built or is ever likely to be built”. Ross Thorne, one of Australia’s most prominent historians of theatre architecture, has called it “a howling gale of modernity”.

It’s startling to think so many of Modernism’s radical monuments are nearing or past 100 years old. In Australia, Walter and Marion Griffin were chief drivers of the movement. Apart from the Capitol, they gave us the design of Canberra, Melbourne’s Newman College and the Fishwick House in Castlecrag, New South Wales, to name a few.

While The Capitol continues to have international claim today, its journey hasn’t been without hurdles.

When The Capitol almost went down

In 1964 The Capitol awaited a major planned demolition. Although this didn’t eventuate in its entirety, the lower level, including the foyer and the stalls, were quickly replaced for a tatty, inconsequential arcade that to this day reeks of the 1960s.

The fight to save the rest of the theatre was a turning point in Australia’s heritage building conservation efforts. For the first time, 20th-century buildings were included alongside the 19th century’s as being worth a thought.

Attitude towards heritage changed after that, although not fast enough to save many of the Griffins’ superb modern buildings. It couldn’t, for instance, save Leonard House. This crystalline wall-fronted structure – built in 1923–24 and demolished in 1976 – sat just a block away from The Capitol.

A new kind of Modernism

Boyd and others have cited the Griffins’ links to Functionalism.

This architectural style, often associated with Modernism, is summed up in a quote from Swiss Functionalist-Modernist architect Le Corbusier: “a house is a machine for living”. In Functionalism, the unornamented functioning of the “machine” is itself considered beautiful.

But like many of the greatest modern buildings, The Capitol is far from functional. In its dazzling ceiling, architecture is recast – originally in timber and plaster – as a living rock, lit with coloured bulbs connected to hundreds of switches.

The interior resembles a limestone cave – like something growing from a crystal. In this respect, it represents the animated and symbolic – the mystical, even – while Modernist architecture was supposed to be dispassionate, industrial and agnostic.

Much like Antoni Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia (started 1882), or Hans Scharoun’s Berlin Philharmonie (1960–63), The Capitol was encountered as an amazing surprise in the centre of an often grimly industrial city.

It allowed you to sit, for two to three hours, in a crystalline envelope of rock, imaged in vibrant colour-changing light. Some experts have attributed the interior to Marion Mahony Griffin. It could have been: she was the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s second female graduate in architecture.

Much like the now vanished Reinhardt Theatre or the Great Theatre in Berlin (1918–19) – with its striking stalactite ceiling – The Capitol is imbued with the mysticism of nature manifest, in dynamism and movement and in lines of force.

Treasures hidden in a cave

The Capitol could have even been considered the Stadtkrone or “urban crown” of Melbourne. This concept, first proposed by Expressionist architects in the early 20th century, envisions cities having a central, symbolic structure that serves as a spiritual and social centre.

In Sydney, the main candidate for this title is arguably Jørn Utzon’s Opera House (1956–73). The structure sweeps the city up into its towering Gothic arcs and projects it, in luminous force, over the harbour.

But The Capitol sits concealed, deep inside another building. It embodies a cave, formed by the marvel of a huge steel beam supporting the offices (now residences) overhead. Only when you enter the hall do you see it teeming with rock-like intricacy.

Dealing with local hostility

Much is made of the Griffins’ “struggle against Australia” – how only in Australia could the pair have had such a hard time. They faced the desk emperors in Canberra, venomous criticism from George and Florence Taylor, the founders of the Building Publishing Company, and the whisperings of rival architects.

Marion herself cast her compiled memoir The Magic of America as a set of battles. But architects face these hurts over and over. Australia was, in fact, surprisingly generous towards the Griffins, given the time and culture.

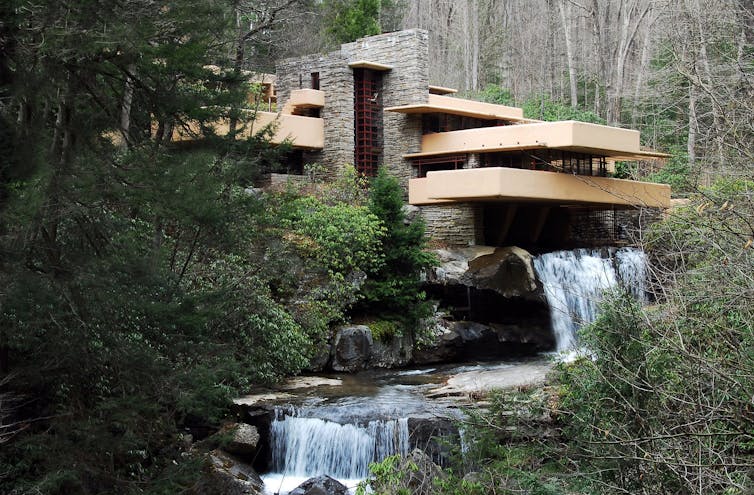

They worked here from 1914 to 1936. In that period, American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, their great contemporary (who was already a titan in his home country), had 52 completed projects – just over one-third of the Griffins’ Australian total of 146 realised projects.

How rich was The Capitol – both building and theatre – in its idea and undertaking. And how sure the Griffins seemed – despite all their qualms in Canberra – about the joy their designs could bring to Australia.

Through The Capitol they paid Australia a great compliment, some three decades before the Sydney Opera House aimed to do the same.

Conrad Hamann works for RMIT University, which owns The Capitol.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.