House of the Dragon chronicles the fall of the Targaryen dynasty some two centuries before life on the continent of Westeros is upended by war and a mini ice age – the events dramatised in HBO’s Game of Thrones.

The new series’ first episode powerfully suggests that political instability and dynastic decline begin with disease and health crises.

The ruling Targaryen King Viserys I suffers from a large and painful pus-filled open wound on his back. He dismisses this injury as a minor one he sustained from sitting on the famous Iron Throne forged with the swords of the vanquished.

His wife, the heavily-pregnant Queen Aemma Arryn, who has endured multiple miscarriages and infant losses in her lifetime, is worried about the health of their unborn baby. The childbirth depicted in this episode is extremely traumatic.

The diseases and medical afflictions that plagued the ruling houses of Westeros – pregnancy complications, madness and genetic disorders – affected the real royal families of Europe during the medieval and early modern periods. And just as in House of the Dragon, these afflictions shaped real dynastic struggles.

Genetic disorders

Like the fictional Targaryens, real European royals frequently married close relatives, contributing to genetic disorders in their families.

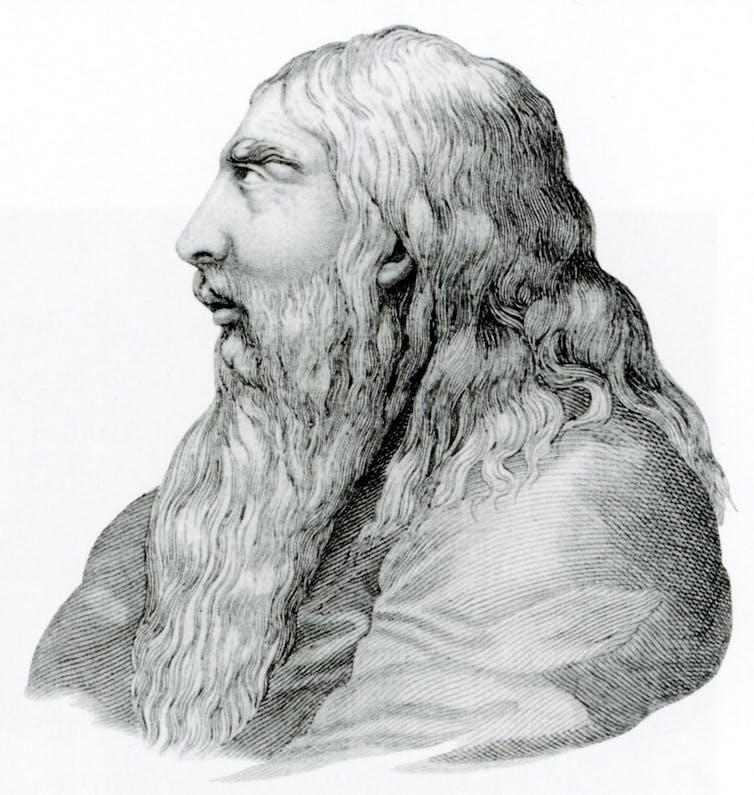

Spain’s last Habsburg king, Charles II, is a poster child for royal incest. He suffered from multiple health problems before his death at 38, including an extreme case of the so-called Habsburg jaw or badly misshapen mandible that made it very difficult to speak and to chew food. His parents were uncle and niece. Geneticists have argued that consanguinity, or parents being descended from the same ancestors, caused this condition.

Queen Victoria of England passed the gene that caused the recessive blood disease hemophilia to the royal families of Russia, Spain and Germany through the marriages of her children.

Victoria’s great-grandson, Alexei Nikolaevich, Tsarevich of Russia, inherited this disease. The holy man Rasputin, who was brought into the palace to treat the Russian Tsar, came to meddle in government affairs, leading to rising tension within the aristocracy and public distrust of the royal family. In this roundabout way the “royal disease,” as hemophilia is known, contributed to the revolution that ended the Romanov monarchy.

Pregnancy and fertility

The primary goal of royal marriage, in both early modern Europe and Westeros, was to bring together powerful families and produce living heirs who would carry on the dynasty.

House of the Dragon’s creators have been criticised for the graphic childbirth scene in episode one, yet they were correct in portraying pregnancy as dangerous for royals. Seven queens and princesses of Asturias (heirs to the Spanish throne) had children between 1500 and 1700. Four died of pregnancy-related causes.

While childbirth could prove fatal to royal women, failure to produce an heir could also see the end of a dynastic house. The history of the island of Westeros, which looks incredibly similar to the British Isles, mirrors much of Britain’s history too. The desire for a male heir could tear apart royal families.

In 16th-century England, King Henry VIII (who also sported an ulcerated wound on his leg, perhaps serving as inspiration for Viserys I’s back wound), would famously break away from the Catholic Church in Rome and marry six times to secure male heirs that would sustain the Tudor dynasty. Ironically, it was eventually Henry’s daughters Mary I and Elizabeth I who took the throne after their brother, Edward VI, died at the age of 16.

Queen Anne famously endured at least 17 pregnancies in 17 years. She gave birth to 18 children, many were stillborn and only one lived to the age of 11. Without an heir, the throne was passed to the Stuart’s German cousins, the Hanovarians.

Mental illness

King George III of England suffered from manic episodes that lead to government instability and regency crises, just like the mad King Aerys Targaryen in the world of Game of Thrones. Various medical conditions have been offered to explain the historic monarch’s madness, including porphyria, a genetic blood disease that can lead to anxiety and mental confusion, or more recently, bipolar disorder.

George was subsequently portrayed as a mad tyrant king and the reason for England’s loss of its American colonies in the American Revolution. However, in reality the British monarchy was constitutional by this point and George had little direct influence on the colonies.

Treatments

Historians might expect to see more religion combined with medicine in Kings Landing if the creators of The House of the Dragon wanted to create a royal household that closely resembled those of early modern Europe.

Sick and injured Catholic monarchs sought out the healing powers of sacred objects. In the 17th century, pregnant queens of Spain were loaned the “santa cinta” or the “holy belt”, a relic that was believed to have belonged to Mary, the mother of Jesus. Wearing or touching this item of clothing was believed to give protection to pregnant queens and their fetuses.

The corporeal remains of deceased holy men and women who were known as saints also played a part in healing Catholic monarchs and their families.

When Prince Don Carlos of Asturias, heir to Spain’s King Philip II, sustained a life-threatening head injury in 1562, Franciscan friars brought the corpse of Fray Diego de Alcalá to the prince’s bed chamber and placed it in his bed. Early moderns attributed Don Carlos’s recovery to this relic and the cranial surgery that doctors performed to save his life.

In a protestant country like England by the late 18th century, treatments were far more conventional to modern eyes, if not more brutal as well.

Treatment of mental illness, including George III’s mania, involved straitjackets and restraining chairs, the latter of which George, who still retained his humour, often called his “coronation chair”. Not quite the Iron Throne, but a throne for a “mad king”, nonetheless.

Sarah Bendall receives funding from Australian Research Council and Pasold Research Fund.

Kristie Patricia Flannery does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.