Whenever I'm walking around my shopping precinct (the Elmsleigh Centre in Staines, Middlesex, if you really want to know) I always find it very hard to walk past the beguiling Games Workshop emporium without giving it a second glance.

More often than not I find myself pausing to peer at the earnest young lads inside, grouped around the game stable and plotting elaborate military manoeuvres with their miniature orcs and elves. And all the while I’ve got a wistful glint in my eye. That’s because, way back in the mid-70s, I too was obsessed by the genre of sword and sorcery, so the sight of my friendly neighbourhood Games Workshop in full, fantastical flow always brings some whimsical memories rushing back.

I admit it: I used to live in a mad world of demons and wizards; dungeons and dragons; broadswords and battleaxes. I used to devour novels by Robert E Howard, creator of Conan The Barbarian. I knew every word of The Hobbit by heart. I had all of Michael Moorcock’s books; I was enthralled by the author’s cunningly conceived ‘Multiverse’, and I loved his character Elric of Melnibone (the albino king with his soul-devouring rapier, Stormbringer) best of all.

Of course, all this has been reduced to utter nonsense these days (I blame Terry Pratchett). But it made perfect sense to me, way back in the mists of time… especially in 1975, when the call of the Great God Cthulhu somehow wafted over to conservative Canada and summoned up Fly By Night, the second album by Toronto trio Rush. By Odin’s beard! I immediately found myself infatuated with this band.

Earlier, Rush’s self-titled debut had more or less passed me by. With John Rutsey hitting the skins alongside guitarist Alex Lifeson and bassist/vocalist Geddy Lee, I had pigeonholed the group as a fair-to-middling hard rock power outfit in the classic British mould of Cream and Led Zeppelin, although Lee’s chipmunk squeal certainly set Rush apart from the pack. Was that a good or bad thing? It was difficult to say, but I didn’t worry about it unduly at the time.

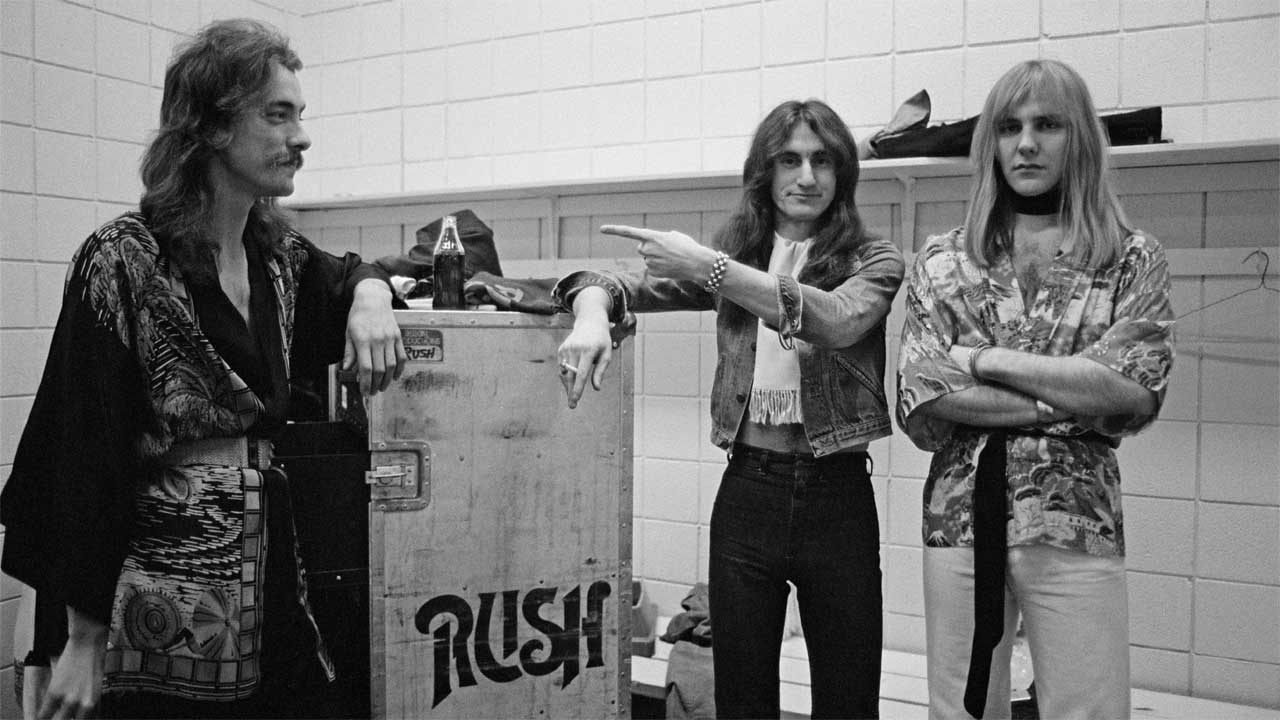

However, Fly By Night marked a Rush Renaissance – yes, with a big capital ‘R’ – as the band adopted a brand new, deeply flamboyant mind-set. Having acquired a flashy, twirly-moustached drummer called Neil Peart, the three-piece shifted direction dramatically.

They became mystical and grandiose; enchanted and other-worldly; weird and wondrous. They garbed themselves in flowing kimonos, voluminous blouses and satin trousers. They began to sing about ‘misty mountains’ and ‘sighing trees’ and places ‘where the Dark Lord cannot go’. They visited the tobes (tobes?!) of Hades and traversed the river Styx. And, of course, they related the tale of the cataclysmic clash between By-Tor and the Snow Dog.

I listened to this epic struggle between good and evil countless times on my unwieldy hi-fi headphones, the initial skirmishes between the two mythical creatures first resounding in my left ear, then running across the forehead to my right ear, the final denouement taking place in the epicentre of my cerebellum.

Wow! This was the battle of Helm’s Deep distilled into the single groove of a humble vinyl record. Nice work, producer Terry Brown. Suddenly Rush had become my favourite band in the entire world. The love affair continued, from Caress Of Steel (didacts and narpets, anyone?), via the jaw-dropping 2112 (the tour de force concept piece where Rush really assumed control of my senses), right through to the live masterwork All The World’s A Stage (straightforward, good-time rock’n’roll tracks such as What You’re Doing and Finding My Way now offering an agreeable counterbalance to Rush’s more grandiloquent rallying calls).

Then came A Farewell To Kings, my favourite Rush album of them all. As a writer on Sounds, I actually spent a few days with the band while they were making …Kings down at Rockfield Studios in Monmouth, South Wales. I remember venturing into a cow shed adjacent to the studio where a vast, elaborate drum kit had been set up.

Birds twittered outside and a gentle breeze blew up, rustling in through the doors and causing some of Neil Peart’s giant wind-chime devices to tinkle back in response – listen carefully, and you can hear it all happening on the record.

Yea verily, there be magick in the air.

But sadly I fell out of favour with Rush when they came up with the Hemispheres album in November 1978. I should have known something was afoot when Geddy Lee told me in February that year: “Synthesisers are going to play a bigger part on the new album. That’s something I’ve been working on. I’ve just acquired an Oberheim Polyphonic and I’ve been trying to figure out how to play it… I think I’ve got the hang of it now. It can make endless sounds, and I’d like to incorporate it into the album…”

These were desperate, tragic times. When Hemispheres was released, it sounded as if Rush had metamorphosed into nothing less than a turgid, torturous techno-rock trio. Plus, to compound the agony, I didn’t understand the ‘conclusion’ to Cygnus X-1, one of the outstanding tracks on …Kings that the band had promised to wrap up on Hemispheres.

I’m a simple sci-fi soul; all I wanted was to find out what had happened to the spaceship (the Rocinante) after it had plunged into an imploding star – a black hole. But instead of admitting the Klingons were to blame in a tidy Star Trek-style ending, Rush embarked on a baffling progressive-rock marathon packed full of allusions to Greek mythology. I’m sorry, but I didn’t understand a word – or a note – of it.

It took me ages to gather my senses and come to the grim conclusion that Rush weren’t my No.1 band any more. I eventually plucked up the courage to face down Geddy Lee in late 1981, backstage at the Brighton Centre on England’s south coast, when the band were on tour to support their Moving Pictures album. The intro to the eventual article summed up my dilemma succinctly: ‘After the goldRush: Geoff Barton writes his first Rush feature for (count ’em) three years and asks, Is there life after Maple Leaf Mayhem?’

Despite the passage of time, Lee, to his credit, remembered my review of Hemispheres very clearly: “You couldn’t decide whether the album was the best or worst thing we’d ever done, right? That was the most disgusting case of fence-sitting I’ve ever come across!”

But Geddy, I pleaded, all I really wanted from you was a shipshape conclusion to an enjoyable little sci-fi tale about a doomed spacecraft. Really, was that too much to ask?

“It took a left turn, that tune,” Lee admitted. “We did the first part on …Kings and that was great, but when we sat down to write the second part we found that we really didn’t know where to take it. But we’d already said ‘to be continued’, so we had to do something… Neil [Peart] had been working on this whole Apollo/ Dionysus thing for some time. It wasn’t supposed to be part of Cygnus…, but then after several discussions we thought, well, maybe we can combine the two ideas and kill two birds with one stone.”

My review of the Brighton show summed up my aversion to Rush’s new direction: ‘They have become a horrific hark-back to the early 70s,’ I wrote, ‘when cold “technique”, finger-flashing “expertise” and m i n d - b o g g l i n g “musicianship” were revered above all else, and for all the wrong reasons.’ In the end, I found myself in full-on begging mode with my one-time Rush hero.

“Some time in the future,” I whimpered at Geddy pathetically, “is there any chance of the band composing some more sword and sorcery numbers? In fact, just one would do. It can be as long or as short as you like. Pretty, pretty please?”

“It’s unlikely, to be honest with you, Geoff,” Lee replied. “That’s the difficult thing about being a fan of a band – any band. I’ve done the same sort of thing myself: you sort of tune into a group at a particular moment; you’re drawn by the material they were playing at that particular stage in their career.”

In fact Geddy was spot-on with his comments. But I wasn’t listening.

“From our point of view,” he continued, “we can’t stay in that moment. That’s why so many groups break up – they figure, well, we’ll keep on doing the same thing. But after a while they become bored and complacent, and stop caring about what they put on record. And their audience stops caring too.”

Geddy’s argument was an entirely convincing one, and it’s absolutely true to say that as Rush subsequently strived for, and attained, numerous fresh peaks (to paraphrase Air Supply) I found myself all out of love with the band. But that doesn’t sway my belief that, out of every single one of Rush’s multifarious musical phases, their sword-and-sorcery period was the best. After all, the band played 2112 until the end – and it remained the Goddamn-blasted highlight of their modern-day set.