Before the Big Ten bombshell that would remake the college football landscape, USC was already embarking upon major change. The Trojans had brought in a big-name new coach, Lincoln Riley—poached from Oklahoma at great expense. He was soon followed by a veritable Rose Parade of star transfers, and the Trojans roster was gutted to the studs.

“There’s not one person in here who’s not doing something new,” Riley said in late August. “Every player here is either in a new school, a new system or both.”

How is the remodel going one week into the season? Rapidly. There is drywall, windows and electricity, but come Saturday against Pac-12 rival Stanford in Palo Alto, it will be time to flip the switch and turn on the lights for real.

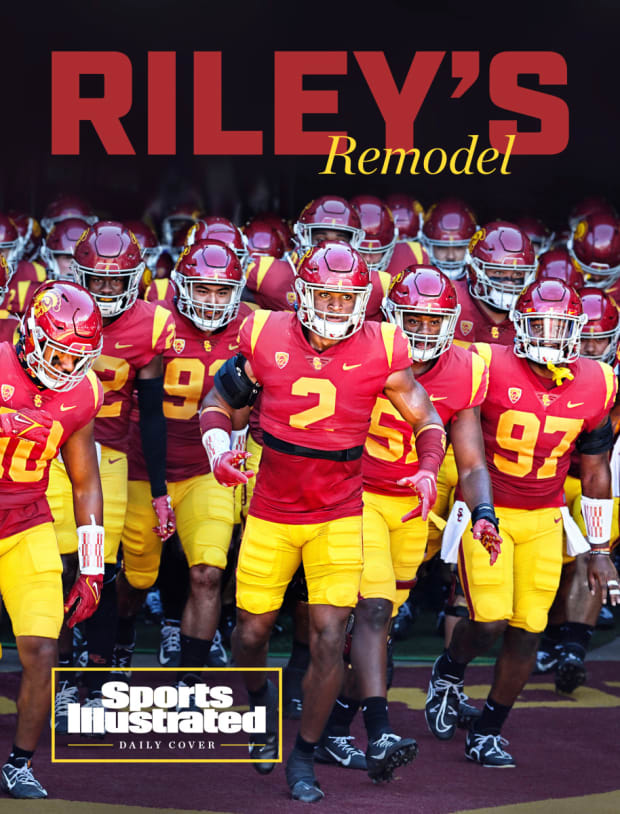

John Cordes/Icon Sportswire/Getty Images

The promising soft launch last week showed how different USC is. Of the 66 points scored in the season opener against poor Rice, 42 of them were produced by players wearing a cardinal-and-gold jersey for the first time. Star transfer quarterback Caleb Williams completed 86.3% of his passes, the highest completion percentage by a Trojan with at least 20 attempts in a decade. The top four rushers (including Williams), along with the eight players of the 12 players who caught passes, are all new to the program. The top two tacklers were transfers from Alabama and Arizona State.

This is the transient nature of modern college football, but cranked up to another level by the coaching change, Riley’s ability to draw talent and the program’s name, image and likeness potential. USC didn’t pay Riley a fortune to rebuild gradually, and he didn’t uproot from Oklahoma for a tedious fixer-upper project. When asked about his first-year expectations during Pac-12 media days earlier this summer, Riley answered: “To win a championship. … This is a go-for-it kind of place. I would reiterate again, we didn’t come here to play for second.”

The most important foundational piece for a rapid rebuild was quarterback, and Riley brought Williams along from Norman to Los Angeles. He was followed by rising-star wide receiver Mario Williams. There were three more notable wideouts from the transfer portal—2021 Biletnikoff winner Jordan Addison (from Pittsburgh) and Brenden Rice (Colorado), son of Jerry. Add in two dynamic multipurpose running backs from within the league in Austin Jones (Stanford) and Travis Dye (Oregon), and Riley quickly amassed the versatile weapons he needs to put his trademark pretty plays into practice.

Constructing a quality defense is the bigger challenge. USC was soft on that side of the ball last year, allowing 31.8 points per game. Riley brought Alex Grinch over from Oklahoma to run the unit and got a whopping three pick-six touchdowns in the opening rout against Rice—USC had a total of two defensive touchdowns (both in 2021) in the previous three seasons combined. One of those scores came from Alabama transfer linebacker Shane Lee.

Stanford, while not in vintage David Shaw form, presents a bigger challenge this week. It also could be one of the last times two ancient rivals meet, as USC and crosstown rival UCLA are set to move to the Big Ten in 2024. Their first contest was in 1905. They’ve played each other 101 times, 10 more than USC has played against UCLA. This is the price of economic progress—losing traditional matchups. In the near future, two SoCal programs that had routinely traveled up the coast to the Bay Area or south to Tucson and Tempe will have to pack the hand warmers and bench heaters for late-season games against strangers in the Midwest and Northeast.

That massive change may have even been a jolt to Riley, who will face long trips and blue lips in his third year on the job, if indeed there is a third year (you simply never know anymore in this business). Riley said the right things in a school release in early July that quoted several coaches in the days after the jarring shift was made public: “This move to the Big Ten Conference positions all of our teams for long-term success. It provides our student-athletes with more exposure, new resources and challenges them with elite competition. USC Football is excited to compete in the Big Ten.”

But in January, a source familiar with USC’s hiring process told Sports Illustrated that when Riley’s previous employer, Oklahoma, decided last summer to make a similarly seismic move along with Texas to the SEC, the coach was not a fan of the relocation. “I don’t think the SEC fit was particularly enticing or popular,” the source said. So the Big Ten is enticing and/or popular? Really?

Luis Sinco/Los Angeles Times/Getty Images

Where will USC be when the Great Migration begins in 2024? On a better talent plane. While Riley’s first five class-of-’23 commitments were offensive skill players who had either been on his radar at Oklahoma or were from the Sooners’ backyard recruiting hotspot of Texas, he then focused on defense and linemen. If the Trojans need to work overtime to elevate their talent to compete in their new conference, they will at least be paid handsomely to make the effort. The Big Ten’s new seven-year, $7 billion-plus media rights package is enough reason to flout tradition and geographic sense these days. The deal will shower money from California to New Jersey, and it is considered not just attractive but necessary. Because, to the South, the SEC is printing money nearly as quickly.

These two rival conferences—backed by rival television networks—have destabilized the rest of the Power 5 in moving to 16 teams each. At SEC media days in July, commissioner Greg Sankey boldly declared his conference a “super league” and flatly answered “yes” to a question about whether adding Texas and Oklahoma is better than the Big Ten’s addition of USC and UCLA. For now, on paper, that is correct. Adding USC and UCLA and their big television market will create more money, though, which theoretically will allow the Big Ten to compete on more even footing with the SEC.

But the two teams from L.A. will enter a conference that is on the wrong side of a wide gap in on-field performance. Three SEC schools have won the last three College Football Playoff national championships (LSU, Alabama and Georgia), and Auburn and Florida have won titles within the past 15 years. The Big Ten’s only title since 2002 came from Ohio State, and the Buckeyes are the only school from that conference to win a championship this century.

Since the playoff era began with the 2014 season, the SEC is 14–5 with five titles, while the Big Ten is 3–5 with one. Ohio State is the only Big Ten member to have won a playoff game, with Michigan State (’15) and Michigan (’21) being routed in the semifinals by SEC opponents. The high-powered Buckeyes look like the strongest challenger to continued SEC hegemony. But with No. 1 Alabama and No. 2 Georgia, the road to the next national title still runs through the South. The West Coast hasn’t seen a glimpse of the national championship in a long time, not since USC won its second straight in ’04.

The Trojans narrowly missed a third title the following season, losing a classic BCS championship game to Vince Young and Texas, and ever since there have been diminishing returns for the preeminent program in Pacific time. Pete Carroll came close a few more times, then beat the NCAA posse out of town and went to the NFL. Amid major sanctions, the program wallowed through coaching dysfunction and mediocre football for a decade.

With USC wallowing, the Pac-12 did the same. Only two teams from the league have qualified for the College Football Playoff: Oregon in the 2014 season and Washington in ’16. USC hasn’t come close to a playoff bid.

Riley was hired to change that. Moving to the Big Ten is a disorienting plot twist in the Trojans’ quest for a return to glory. But this much is certain: USC will have every available resource to compete, and players have flowed in via the portal. It’s not easy to successfully flip a roster in a matter of months, but the Trojans are intent on finding out how fast a total rebuild can happen.

Watch college football live with fuboTV: Start a free trial today!

.png?w=600)