Almost one-sixth of Earth’s land surface is covered in otherworldly landscapes with a name that may also be unfamiliar: karst. These landscapes are like natural sculpture parks, with dramatic terrain dotted with caves and towers of bedrock slowly sculpted by water over thousands of years.

Karst landscapes are beautiful and ecologically important. They also represent a record of Earth’s past temperature and moisture levels.

However, it can be quite challenging to figure out exactly when karst landscapes formed. In our new work published today in Science Advances, we show a new way to find the age of these enigmatic landscapes, which will help us understand our planet’s past in more detail.

The challenge

Karst is defined by the removal of material. The rock towers and caves we see today are what is left after water dissolved the rest during wet periods of the past.

This is what makes their age hard to determine. How do you date the disappearance of something?

Traditionally, scientists have loosely bracketed the age of a karst surface by dating the material above and beneath. However, this approach blurs our understanding of ancient climate events and how ecosystems responded.

Geological clocks

In our study, we found a way to measure the age of pebble-sized iron nodules that formed at the same time as a karst landscape.

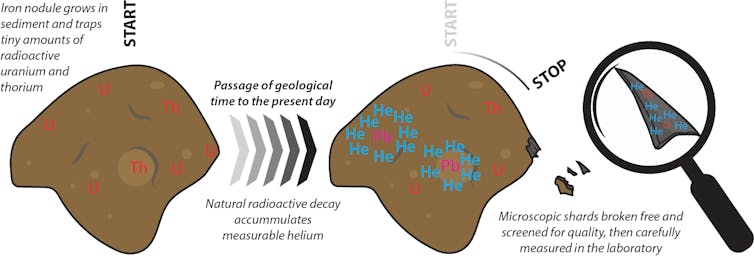

This method has the technical name of (U/Th)-He geochronology. In it, we measure how much helium is produced by the natural radioactive decay of tiny amounts of the elements uranium and thorium in the iron nodules. By comparing the amounts of uranium, thorium and helium in a sample, we can very accurately calculate the age of the nodules.

We dated microscopic fragments of iron-rich nodules from the iconic Pinnacles Desert in Nambung National Park, Western Australia.

This world-famous site is renowned for its otherworldly karst landscape of acres of limestone pillars towering metres above a sandy desert plain. The Pinnacles form part of the most extensive belt of wind-blown carbonate rock in the world, stretching more than 1,000km along coastal southwestern WA.

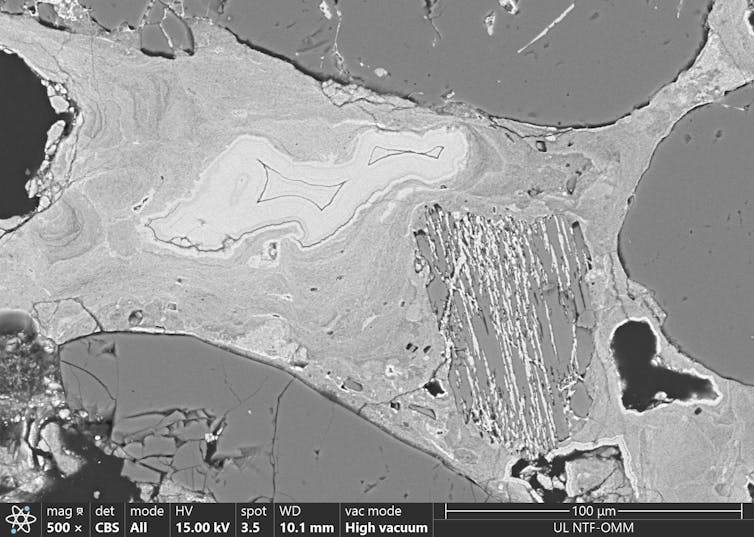

We examined multiple microscopic shards of iron nodules that were removed from the surface of limestone pinnacles. These nodules formed in the soil that lay on top of the limestone during the period of intense weathering that created the karst. As a result, they serve as time capsules of the environmental conditions that shaped the area.

The big wet

We consistently found an age of around 100,000 years for the growth of the iron nodules. This date is supported by known ages from the rocks above and beneath the karst surface, proving the reliability of our new approach.

At the same time as chemical reactions caused growth of the iron-rich nodules within the ancient soil, limestone bedrock was rapidly and extensively dissolved to leave only remnant limestone pinnacles seen today.

From examining the entire rock sequence in the area, we think this period of intensive weathering was the wettest time in this part of WA over at least the past half a million years.

We don’t know what drove this increased rainfall. It may have been changes to atmospheric circulation patterns, or the greater influence of the ancient Leeuwin Current that runs along the shore.

Such a humid interval is in dramatic contrast to the recent droughts and increasingly dry climate of the region today.

Implications for our past

Iron-rich nodules are not unique to the Nambung Pinnacles. They have recently been used to track dramatic past environmental change elsewhere in Australia.

Dating these iron nodules will help to better document the dramatic fluctuations in Earth’s climate over the past three million years as ice sheets have grown and shrunk.

Understanding the timing and environmental context of karst formation throughout this time offers profound insights into past climate conditions, environments and the landscapes in which ancient creatures lived.

Climate changes and resulting environmental shifts have been crucial in shaping ecosystems. In particular, they have had a profound influence on our ancient hominin and human ancestors.

By linking karst formation to specific climatic intervals, we can better understand how these environmental changes may have affected early human populations.

Looking forward

The more we know about the conditions that led to the formation of past landscapes and the flora and fauna that inhabited them, the better we can appreciate the evolutionary pressures that shaped the ecosystems we see today. This in turn offers valuable information for preparing for future changes.

As human-driven climate change accelerates, learning about past climate variability and biosphere responses equips us with knowledge to anticipate and mitigate future impacts.

The ability to date karst features with greater precision may seem like a small thing – but it will help us understand how today’s landscapes and ecosystems might respond to ongoing and future climate changes.

Milo Barham has previously received research funding from the Minerals Research Institute of Western Australia.

Andrej Šmuc, John Allan Webb, Kenneth McNamara, Martin Danisik, and Matej Lipar do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.